Relax: higher interest rates aren’t a calamity for stocks

For some of America’s biggest firms, higher rates will actually mean more profit, argues one Finimize analyst.

26th January 2024 12:09

by Paul Allison from Finimize

- With new fears that inflation might pick up steam again, a lot of people are talking about the damage even higher interest rates could potentially cause to the economy and company profit.

- But provided we’re not talking about a doubling in rates from here, there are few actual reasons to be concerned. In fact, for some of America’s biggest firms, higher rates will mean more profit.

- And as for the valuation argument, well, there’s little point paying attention to current interest rates anyway.

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t like higher interest rates. But they’re not the disaster for stocks that a lot of people make them out to be. And if they stay at these higher levels for a while (or, yes, even climb a little bit), that doesn’t mean your portfolio has to take a beating. Hear me out…

These rates are just fine, actually.

I get it: we’ve just been through the most aggressive hiking cycle in at least 40 years, and that’s enough to make anyone worry about how well stocks and the economy might hold up. Today’s interest rates are around 5%, and that seems astronomical compared to the near-zero rates of just two years ago.

But, look, when it comes to the economy, consumer spending is the dominant force (around 65% of the total). And the US consumer is doing pretty well: they paid off a lot of debt and banked a lot of savings during the pandemic era. Plus, about 90% of American homeowners locked into 30-year mortgages before rates went skyward. So any new hikes shouldn’t damage spending that much – provided the rates don’t double or something.

As for companies, their debt picture doesn’t look too bad either. Sure, very few of them have the luxury of a 30-year lock-in period on what they owe, but plenty have some of their debt issued with repayment at least a few years out in the future. And that gives them a nice cushion against the impacts of higher rates.

On top of that, there are three fundamental ways that higher rates could become problematic for companies, or their share prices. First, if companies are eyeballed with debt, the higher interest payments they’ll be forced to make will cut deep into their profit. Second, higher borrowing costs could slice into potential business investment, which could hurt profit growth. And third, those higher rates would make future profit less valuable today, which would drag down valuations. I’ve been crunching some numbers on these three factors. Here’s what I found.

1. The real cost of higher rates.

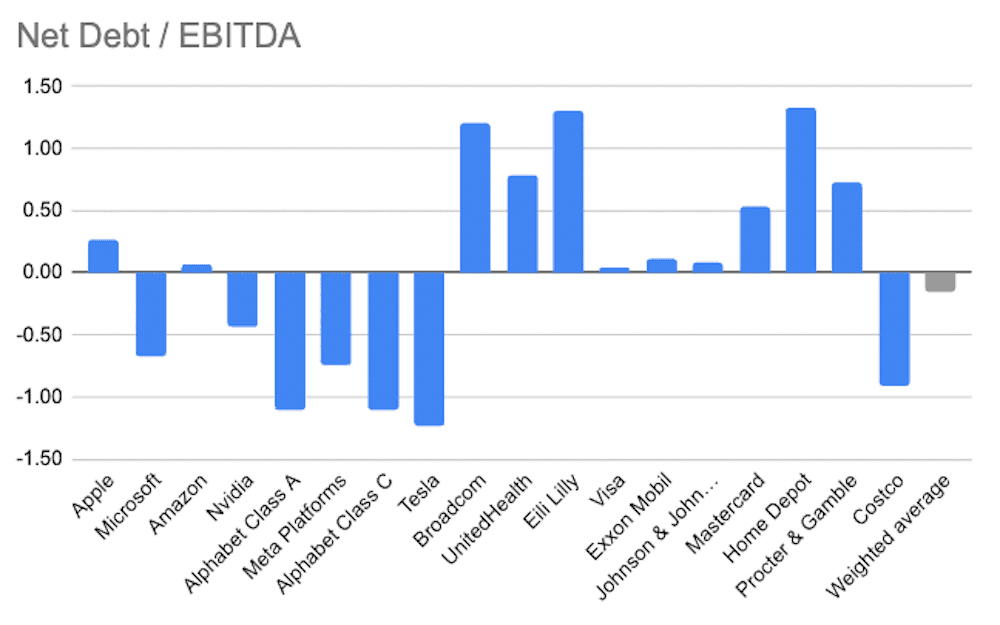

First things first: take a look at this chart – it’s a snapshot of the biggest 20 firms in the S&P 500 (18, actually, because there’s no point including JPMorgan and Berkshire Hathaway: this calculation doesn’t work for financial firms). The blue bars show the size-weighted net debt – that’s debt minus cash in the bank – relative to profit. These 18 firms make up nearly 40% of the entire S&P 500.

Net debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) for the biggest 20 S&P 500 firms excluding JPMorgan and Berkshire, using the most recent annual filings. Source: Koyfin.

I should point out that this chart uses only the actual long-term debt recorded on each firm’s balance sheet and it doesn’t include any shop, office, or factory long-term leases that are also recorded as a liability (even though no actual funds are borrowed). Given the makeup of the S&P 500, though, this extra debt wouldn’t change the conclusion here, which is that among these 18 hefty firms, seven have more cash than debt (and it’s mostly the biggest of the big too). What’s more, the size-weighted average of these firms is also in a “net cash” position, and even for those firms that have more debt than cash, the proportion relative to their profit is very low – with most carrying less than one times debt to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization, or EBITDA. In other words, they make more profit in a year than they carry in debt.

So, the reality is that for most of these massive American companies (remember, they represent nearly 40% of the S&P 500) higher interest rates is a minor inconvenience at worst, and for many – those Big Tech monsters like Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta – it’s actually a net positive because the interest they’re earning on their cash should more than offset the interest payments they’re making on their debt.

2. Impact on business investment.

Another major challenge that higher rates could pose is on the amount of cash that companies are able to invest in big projects and other growth initiatives. This “capital spending” is vital to any firm’s future. Now, some will borrow money to fund these investments, but that’s typically only if they can do so at a pretty good rate. If not, most finance chiefs would turn to the companies’ internally generated profit to fund this spending. So the question is, then, do these firms produce enough cash to meet those business-expanding outlays?

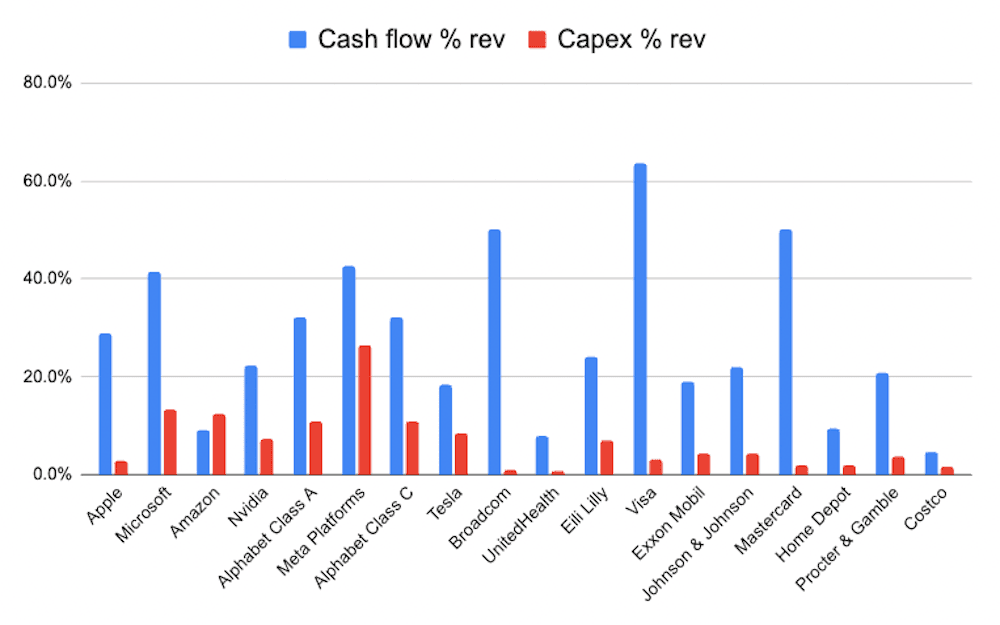

This next chart shows those 18 companies’ capital spending (red bars) and cash flow (blue bars) relative to their sales. I’m using operating cash flow here, which is the actual cash produced after all day-to-day expenses, interest payments, and tax, but before those big budget outlays, dividends, and share buybacks.

Company operating cash flow and capital spending as a percentage of revenue, using the most recent annual filings. Source: Koyfin.

This chart is actually pretty remarkable – if you’re looking for the perfect picture of why American firms are so unstoppable, this is it. Just look at how the blue bars (the amount of revenue these firms convert to cash flow) tower above the red bars (the amount of money – as a percentage of sales – these firms spend on big project outlays). More than half of these firms convert over 20% of their sales to cash flow – in other words, they’ve got a cash flow margin above 20%. And a few (Visa, Mastercard, Broadcom, Meta, and Microsoft) convert more than 40%.

By contrast, only one of them (Meta) spends more than 20% of sales on capex. Most spend less than 10% – with plenty in the low single-digit range. Now, there’s one exception to this: Amazon. The ecommerce (and cloud) giant has been spending more of the cash it generates on building massive data centers. That won’t be the case forever, though, and the firm has a very healthy balance sheet with basically the same amount of debt and cash.

So here’s what you can take from this: US firms produce mountains of cash flow, with enough to cover their spending plans and plenty left over for other stuff like dividends, share buybacks, or even acquisitions. So in reality, there’s actually no need for these firms to take on any debt whatsoever – at any interest rate.

3. Valuations.

I’ve got just one point to make here, and I’ll do my best to keep it simple. First, remember that when interest rates rise, today’s value of future profit goes down. That’s because those future profits are converted to today’s value by dividing by the discount rate, and interest rates are the biggest piece of that.

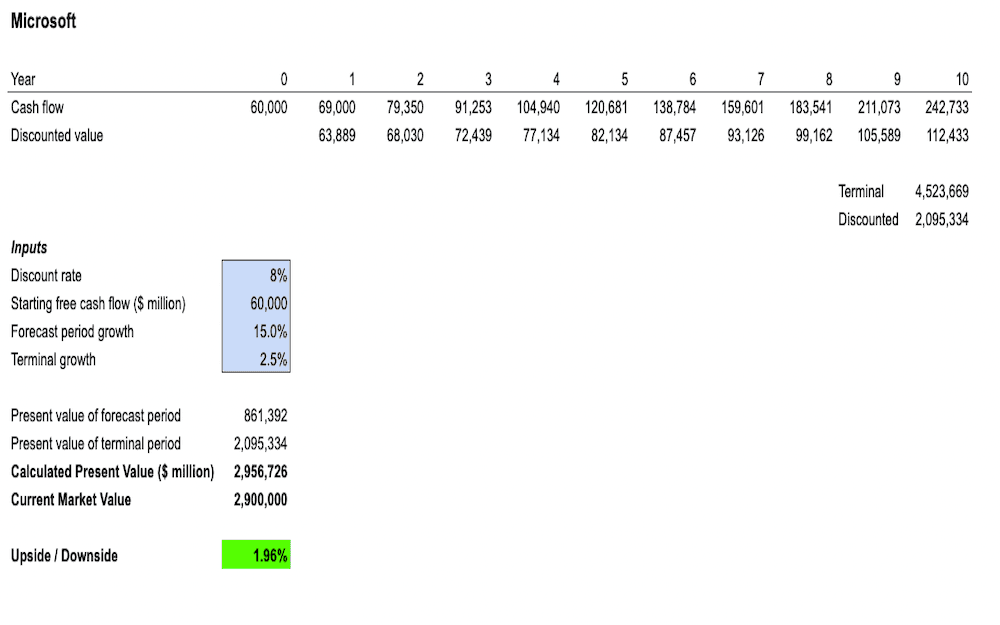

Next, let’s take Microsoft as an example. Below is the firm’s discounted cash flow (DCF), which takes forecasts of the firm’s future profit streams (cash flows) and divides them by a discount rate to get today’s company value.

Microsoft’s discounted cash flow (DCF). Source Koyfin, Finimize calculations.

The calculations take Microsoft’s cash flow ($60 billion) and assume it will grow at 15% a year for the next ten years (that’s not unreasonable) and then at 2.5% after that (roughly, the level of economic growth because nothing can grow faster than the economy forever). It then discounts that by 8% and gives you a value roughly equal to today’s market value of the firm – $2.9 trillion.

Okay, note that I used a conservative discount rate of 8%, not the current 4% rate for the 10-year Treasury plus a bit to account for stocks being riskier than bonds. And, to be honest, if I’d done the same calculation three years ago when those 10-year rates were at 1%, I’d still have used 8%. That’s because any analyst worth their salt should use an appropriately high discount rate when valuing companies. That’s why, when everyone says that higher rates kill valuations, my strong pushback is that they shouldn’t if you’re using an appropriate discount rate to begin with.

To highlight my point further, rewind three years to the beginning of 2021. Let’s say back then you were thinking Microsoft would grow cash flow by around 10% a year for the next ten years and not 15% (remember, very few people were talking about AI back then), and then the same 2.5% after that. Well, Microsoft was valued at $1.6 trillion back then, and guess what discount rate would have converted those future forecasted cash flows to equate to $1.6 trillion? Yep, 8% (roughly). And that’s when interest rates were near zero.

So, while it’s true that higher discount rates lead to lower valuations, higher interest rates shouldn’t if you’re using an appropriate rate in your valuation calculations to begin with. Just for fun, had you thought a discount rate of 6%, say, was appropriate in your math three years ago (I mean, that was five percentage points higher than Treasury yields at the time, after all), you’d have computed a valuation for Microsoft of $2.5 trillion back then. Ironically, if you’d been dumb enough to believe your own math, you’d have piled into the stock and made an absolute killing, but that’s by the by I suppose.

Paul Allison is a senior analyst at finimize

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.