Lloyds Bank shares: Brexit discount 'too good to miss'

Jamie Clark, co-manager on the Liontrust Macro Equity Income fund, gives his view on UK banks.

28th March 2019 12:13

Jamie Clark, co-manager on the Liontrust Macro Equity Income fund, gives his view on UK banks.

How 'Brexit discount' has created a margin of safety in shares of UK banks

The UK-centric nature of Lloyds Banking Group (LSE:LLOY) and Barclays (LSE:BARC) means that they have been hit heavily by the 'Brexit discount'. Their valuations now price in a Brexit recession that may never happen, providing a substantial margin of safety which allows us to confidently invest in these businesses on Macro-thematic grounds.

Time was when we wouldn't touch large-cap UK banks with the proverbial ten-foot barge-pole. We felt deeply uncomfortable about the contribution of banks to the global financial crisis and the way this made them vulnerable to open-ended recriminations.

In pursuit of returns, the pre-crisis era saw loan books swell as credit was extended on overly-lax terms. This created credit quality issues and meant that wafer-thin capital buffers were depleted when the crisis erupted. Non-performing loans continued to lurk unseen in the darkest recesses of complex balance sheets.

Seemingly ignorant of their own role in this mess, regulators and politicians were quick to attribute blame. Banks were subject to financial penalties, stricter oversight and higher capital standards. Lower shareholder returns ensued.

This was a deeply unattractive set-up for investors and it's little wonder that UK banks, with the exception of HSBC (LSE:HSBA), have performed so poorly in the last decade. We had zero-weighting to large-cap UK banks for much of this time.

But, as the Righteous Brothers crooned about matters less arid, 'time can do so much'. In the last decade, UK banks have made strides in atoning for the errors of the pre-crisis period. Balance sheets are smaller and less geared, capital cushions are more robust, loan funding is more sustainable and surplus capital is now returned to shareholders.

The fruits of self-help complement our view that global rates have bottomed, which is the crux of our Rising Rates Macro Theme. Higher rates allow banks to progress margins, as loans are repriced more quickly than deposits. They should also be earnings accretive, as sleepy, low-yielding current account balances are deployed in interest rate hedges. Not to mention that higher rates are typically consistent with economic growth, rising credit demand and fatter bank profits.

This may seem a tough argument to make, given the Fed's March moratorium on tightening. But it's imperative to untangle cyclical influences from the long-term factors that may push rates higher in time. A mesh of demographic, political and structural forces tell us that UK rates are at their lowest ebb. More on this to follow in my next blog.

But the real clincher in favour of UK banks, is the extent to which Brexit has suppressed the valuations of those companies with domestic exposure and gifted us an attractive buying opportunity. Last year we took full advantage of this, in initiating overweight holdings in both Lloyds and Barclays.

The referendum was a moment of rupture on several counts. Aside from the obvious political and social schisms, it drove a wedge between the performance of UK businesses with domestic sales and those with international revenues. Since the referendum, the FTSE local United Kingdom Index has trailed the more international FTSE 100 by around 32%.

The argument seems to be that because Brexit is without precedent, predictive models offer little insight and UK-centric assets warrant a discount. This is moot and likely says more about the limitations of forecasting. Far more tangible, is the fact that the likes of Lloyds Banking Group and Barclays appear cheap by the standards of history.

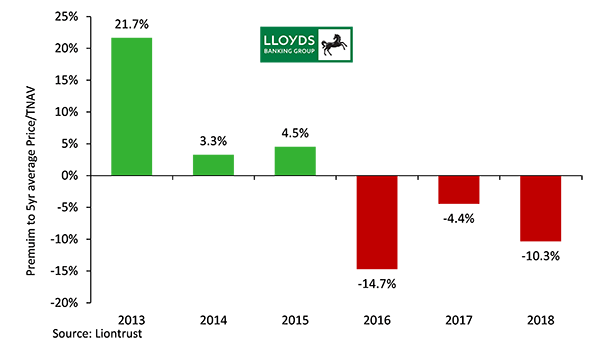

We demonstrate this below in using a measure known as Price to Tangible Net Asset Value (P/TNAV). This simply expresses whether a bank's share price is cheap, or expensive relative to the per share value of its net tangible assets.

The charts show both Lloyds' and Barclays' P/TNAV ratios compared to the average of the last six years. Both banks' have traded at a discount to their average since the 2016 referendum. Lloyds' share price has typically traded at 1.34x TNAV over this period, but now sits at 1.19x, a 10% discount. Barclays trades at 0.63x, a 21% discount to its 0.79x six year average.

Prospective earnings multiples yield the same insight. Over the same six year period, Lloyds has on average traded at nearly 10x forward earnings and Barclays at 10.25x. Following the referendum, both banks slipped to material discounts; Lloyds presently sits at a 20% discount to the average, whilst Barclays 30% discount makes it look as popular as a tax demand. Make no mistake, both banks are already pricing a Brexit recession that may never happen.

But 'so what?' you might say. Cheap doesn't necessarily mean good value. This is partially true, but it does give us a margin of safety. That is, by buying a good business on attractive terms, we also acquire a cushion against the vagaries of markets, analytic errors and inescapable behavioural biases. This is a nugget of common-sense closely associated with value investors like Ben Graham and Seth Klarman.

Our margin of safety in Lloyds and Barclays looks wider still, if we consider the gap between their modest valuations and the abundant operational progress they've made in the post-crisis era. Capital reserves are bigger and, as per the Bank of England's Financial Stability Report, sufficient to weather another financial crisis; whilst improving measures of shareholder returns demonstrate that these are well run and increasingly profitable businesses.

In turn, this has significant implications for cash returns. Both Lloyds and Barclays are intent on growing ordinary dividends as circumstances permit. Barclays' strong full year update also signalled that it will soon join Lloyds in returning surplus capital through share buybacks.

This is manna for income investors like us and only serves to demonstrate that the Brexit discount is offering us a margin of safety that's too good to miss.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.