How money is really created in a modern economy

Hint: central banks don’t have much to do with it. Stéphane Renevier’s got a breakdown that can help you understand the whole scene.

6th June 2024 12:20

by Stéphane Renevier from Finimize

- Contrary to popular belief, central banks aren’t the lead players when it comes to creating money. They play second fiddle to commercial banks, which can make new loans with deposits created right out of thin air.

- That doesn’t mean they can create money without limits: they are restrained by profitability concerns, strict regulatory capital requirements, and the need for market confidence, all of which prevent unrestricted lending. Broader economic conditions and central bank monetary policies also have a significant effect on loan demand and supply.

- To get useful insights into the economy, you could track broad money indicators (essentially: currency held by the non-bank private sector and bank deposits), like the M2, M3, or M4.

Here’s something that might surprise you: contrary to popular belief, central banks aren’t the lead players when it comes to creating money. They play second fiddle to commercial banks, which are the real source of it all. And maybe that seems like useless financial trivia, but it’s actually not. Here’s what it means and why it matters.

First, what is money?

Money today is more than just paper and polymer notes and tiny metal discs: it’s a globally trusted IOU that circulates through the economy, paving the way for the exchange of goods and services.

There are three main types of money: currency (your everyday coins and bills), bank deposits (including your run-of-the-mill accounts for consumers and certain bank bonds for investors), and central bank reserves (funds that commercial banks hold in accounts at the central bank, which are used to manage liquidity and fulfill other monetary requirements).

Each of those three represents an IOU from one place in the economy to another. With currencies, it’s from the central bank to (mostly) consumers. With bank deposits, it’s from commercial banks to consumers. And with central bank reserves, it’s (naturally) from central banks to commercial banks.

Currency held by the private sector (other than banks) and bank deposits make up what’s considered the “broad money” – the fuel for important spenders like households and companies.

And that remaining piece, central bank reserves pairs with currency to form the “base money” – the central bank’s stake in the financial game.

The vast majority of money in the modern economy is in the form of bank deposits: in the UK, it’s about 79%, with another 18% in reserves, and 3% in currency.

So, then, how is money actually created?

A lot of people assume that central banks and governments are responsible for actually creating the money. But the surprising truth is, most of what flows around actually springs from commercial banks, those everyday financial institutions we use for direct deposits and bill-paying.

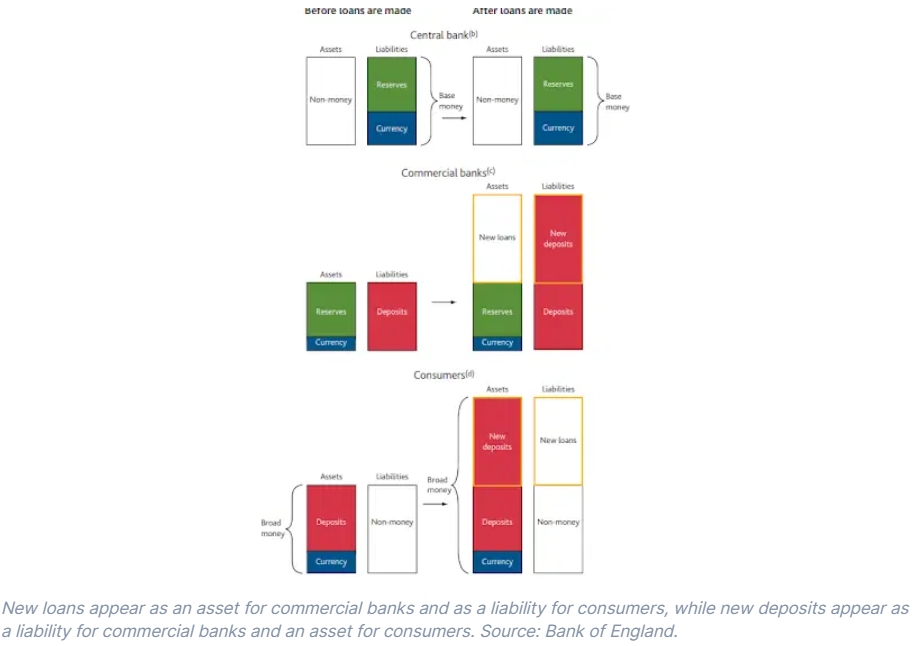

See, commercial banks can easily create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans. When they approve loans, like for a new house or a car, they don’t dole out physical cash. Instead, they just jot the loan amount as a deposit right into your bank account – and boom, new money is born, a process so slick it’s nicknamed “fountain pen money”. That new loan shows up as an asset on the bank’s ledger, while simultaneously, a matching deposit is logged as a liability.

But this money can disappear just as quickly. Consider your credit card shopping spree; it boosts the store’s cash register balance but piles up your debt. Settle that bill at the end of the month, and your bank shrinks your balance owed – and poof, the money vanishes. Sure, there are other ways money can be created (like “quantitative easing”, or QE, which we’ll get to later) but when it comes to the sheer scale and economic impact of newly created money, commercial banks are the real MVP.

Wait, money isn’t just created by central banks?

It’s definitely not. And while we’re on the subject, let me bust a few other myths.

First, contrary to popular belief, banks aren’t just middlemen, holding and lending out the deposits savers give them. In reality, the act of lending itself generates these deposits. See, banks essentially create new deposits right out of thin air – without first having money deposited with them. And that’s a major shift from the traditional “multiplier model” you might have read about in some dusty old textbook, where deposits start the lending process. The point is, banks are so much more than an intermediary.

Second, central banks are only secondary players in the creation of money. That’s because they have little direct control over the amount of credit issued by commercial banks – which then gets injected into the economy. The influence that those policymakers have is far more nuanced, and primarily comes through setting and influencing interest rates, which, in turn, improves or worsens the lending opportunities available to banks.

Third, money creation depends mainly on the confidence and incentives of the banks. When they are confident, they create new money by giving the okay to credit and new bank deposits. But when they’re fearful, they get shy about lending. And, really, it’s those lending decisions that determine how much money gets created.

Can regular banks just create money without any limits, then?

Thank goodness, no. Banks aren’t free-wheeling money printers: they operate within a tight framework that keeps wild lending in check. Banks have to stay profitable – and when loans default (remember: the associated deposit is a liability for the banks), that hurts their bottom line. Plus, they’re under the watchful eye of regulators who set strict rules on how much capital they need to hold against the loans they make. And, finally, their reputation in the market matters. A bank that’s seen as risky might find itself frozen out of interbank loans, which are crucial for maintaining day-to-day operations, or they could become vulnerable to a bank run, with customers attempting to withdraw all their deposits all at once. This combo of profitability concerns, regulatory requirements, and the need for market confidence keeps banks from going on a fast-and-loose lending bender.

And, keep in mind, the supply and demand for loans are influenced by factors that everyday banks can’t control. That stuff is influenced not just by the overall economic climate, but also by monetary policy (broadly, interest rates), which is set by central banks. And interest rates are a huge factor: by altering lending rates, central banks can make loans more or less costly for consumers , and more or less profitable for banks – affecting how much households and companies want to borrow, and how much banks are willing to lend.

And, one more thing: money creation is also capped by the behavior of the money holders – households and businesses. The ones who receive the newly created money might respond by undertaking transactions that immediately destroy it, for example by repaying outstanding loans. (Again, poof – money gone).

OK, so what was that about quantitative easing, then?

When commercial banks aren’t creating enough money – that is, when folks aren’t borrowing – that tends to send

Inflation to worryingly low levels. And in those times, central banks can try to perk up borrowing and spending, by slashing interest rates.

But sometimes, even that is not enough, and that’s when central banks can resort to a more extreme tactic: QE. It’s essentially a massive asset-buying program that uses freshly minted money to purchase truckloads of government bonds, which boosts the amount of central bank reserves – and hence money – in the economy.

Now, commercial banks and other financial institutions that sell their assets to the central bank will suddenly find their pockets deeper with fresh deposits, having swapped bonds for cash. Issue is, they might find themselves with more cash on hand than they’d like. So to rebalance their portfolios, they’ll likely shift gears and pour this extra dough into juicier assets like corporate bonds and stocks seeking better returns. This shift is expected to pump up the value of these assets, while also making it cheaper for companies to raise the funds they need to expand and develop. The hope is that this has a positive ripple effect on the economy: with companies having access to cheaper capital and households growing wealthier, they’re likely to ramp up spending, giving the economy a nice little boost and putting inflation back toward healthy, stable levels.

But it’s not a perfect system. While QE pumps up the reserves banks hold, it doesn’t automatically compel them to lend more. They could just sit tight, or businesses might take advantage of low rates to simply pay down debts rather than borrow more.

So while QE does increase “base money”, it doesn’t necessarily boost “broad money”. That’s why, in the context of tracking money creation in the economy, paying attention to bank deposits (and broad money) is much more important than central banks reserves (and base money).

Why should you care about all this?

Changes in the money supply can reveal a lot about the spending trends and inflationary pressures within the economy. When broad money increases, it can indicate that banks are ramping up their lending activities, which typically suggests that the economy is doing well. If this lending translates into economic value, it can also point to potential future growth. And that’s reason for real optimism.

There are a few gauges you can use to track broad money. For the US, the best starting point is M2, which measures the total amount of money in the economy, including currency in circulation and various bank deposits (both consumer and corporate). It provides insights into consumer spending and saving patterns, making it useful for assessing and predicting inflation and economic changes driven by consumer behavior.

For Europe, you can keep tabs on the M3 and for the UK, there’s the M4. They’re even broader, covering everything in M2 plus less-liquid assets like big-time deposits and money market funds (in the UK, M4 also includes money held by non-bank financial institutions). By capturing a broader spectrum of financial assets, M3 and M4 offer deeper insights into overall economic health, including investment trends and financial stability, which are also crucial for long-term economic forecasts and for understanding inflationary pressures.

Some central banks also provide more specific measure, like M4 Lending in the UK, which specifically tracks the amount of money that banks are actually lending out to consumers and businesses.

Here’s an example of how M4 and M4 lending have evolved over the past few years in the UK.

Both money (blue line) and lending (orange) grew at a fairly stable rate from 2011 until the pandemic. But then you can see a huge spike in broad money creation, which arguably played a major role in fuelling inflation during that period. But the velocity of money creation has plunged since then, even dipping into negative territory recently – yep, that means money was essentially being destroyed.

Interestingly, despite this massive increase in money supply – at least partly spurred by QE – we didn’t see an increase in lending or a big boost to economic activity (though it probably did give stocks and real estate a lift). That hints at an underlying economic weakness in recent years. But, there’s also a silver lining in this chart: there’s been a recent uptick, suggesting that the economy might finally be picking up some steam again.

Stéphane Renevier is a global markets analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.