How to invest like the best: Peter Lynch

In this three-part series, David Prosser explains how famous investors made their fortunes and how private investors can adopt their strategies. Peter Lynch, who ran Fidelity’s Magellan Fund, is the third to feature.

24th March 2025 09:44

by David Prosser from interactive investor

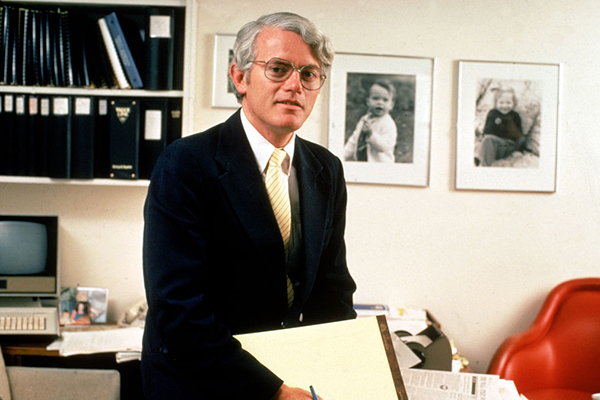

Credit: Steve Liss/Getty Images.

Only the keenest of golf historians will be familiar with Francis Ouimet – but millions of investors owe this American amateur golfer a debt of gratitude. The scholarship fund he launched in 1949 for golf caddies would eventually enable Peter Lynch to go to college – kickstarting the career of one of the best-known investment gurus of the 20th century.

Lynch, born in Massachusetts in 1944, was just 10 when his father died of brain cancer. To help support the family finances, he began working as a caddy at a local golf club, where the conversations he overhead about investment opportunities sparked an early interest in the stock market.

- Our Services: SIPP Account | Stocks & Shares ISA | See all Investment Accounts

Lynch would go on to attend Boston College – courtesy of a Francis Ouimet scholarship – graduating in 1965 with a degree in finance, and enough savings from his early investments to enrol on the MBA course at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. He continued to caddy, including for a prominent local player, George Sullivan, who just happened to be chief operating officer of Fidelity, the Boston-based fund management firm. The connection would help Lynch to clinch his first job at Fidelity, which he joined in 1969.

‘Invest in what you know’

Eight years later, Lynch was appointed to run Fidelity’s Magellan Fund, a small mutual fund largely invested in US stocks. It was an opportunity to put his investment theories into practice. Above all, Lynch operated by the maxim “know what you own and know why you own it”. He argued that investors could often outsmart the professionals by backing businesses they thoroughly understood.

“Invest in what you know” is a deceptively simple idea. “Behind every stock is a company”, Lynch argued, pointing out that most people have interests and activities that bring them into contact with these businesses. Maybe you’re a loyal customer of a particular retailer or work in a specialist field where you know what it takes to succeed. By using your knowledge and insights to identify good businesses, you can start to explore potential investments, analysing their strengths and weaknesses in more detail, and assessing how the market currently values those attributes.

For Lynch, who applied this approach on an industrial scale, this meant hour after hour of research and diligence, analysing every aspect of a business’ balance sheet, and interrogating its senior managers about their operations and plans. But the work paid off handsomely - $1,000 invested in Magellan at the start of Lynch’s tenure would have been worth more than $28,000 on his departure.

Indeed, Lynch’s record at Magellan was unparallelled, with the fund delivering an average annual return of 29.2% for investors during his 13 years in charge. When Lynch took Magellan over in 1977, it was an obscure $20 million mutual fund that few outside Fidelity would even have heard of; by the time he left in 1990, it was the biggest fund in the world, with $14 billion of assets under management. Remarkably, one in every 100 Americans invested in Magellan under Lynch.

The story of this success is told in three bestselling investment books he has written documenting his experience. One Up on Wall Street, published in 1989, Beating the Street (1994) and Learn to Earn (1995) have each sold more than a million copies. Easily accessible and full of the sort of witticisms for which Lynch’s contemporary Warren Buffett is known, they provide practical guides to applying his theories.

An example of Lynch’s share price success

His story of investing in Dunkin’ Donuts is a classic example of the Lynch approach. In the late 1980s, shares in the retailer were trading at lowly levels amid anxiety about competition in the fast-food sector. But Lynch, a big fan of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, was a regular visitor to its stores, where he often noted long queues and repeat customers. That prompted him to investigate the company’s financials and fundamentals; spotting its strong earnings growth and room for expansion, he bought the stock. It would become a “15-bagger” for Magellan, returning more than 15 times Lynch’s initial stake.

Lynch’s strategy paid off because he knew and understood the company, but also because his investigations showed him that it was cheap. “If you can’t find any companies that you think are attractive, put your money in the bank until you discover some,” he advises.

Assessing the attractiveness of a stock can be as much an art as a science, of course, but Lynch paid particular attention to a number of key metrics. In particular, he popularised the use of “PEG ratios”, which he argued offered a better indication of a business’s value than the more widely-used price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio.

A company’s P/E ratio is a measure of its share price relative to the earnings that it generates for each share; in other words, it shows you how much you must pay for the earnings the company is producing. A PEG ratio, by contrast, is a measure of the company’s P/E ratio relative to its expected growth rate, based on analysts’ estimates. It shows you how much you’re paying both for earnings today and the company’s potential future earnings.

The lower the PEG ratio, the more the stock may be undervalued given its future earnings expectations. Lynch looked for businesses with a PEG ratio of less than one, the ratio he suggested denoted a fairly valued company.

Growth at a reasonable price

Such methods explain why Lynch is now widely regarded as the original “growth-at-a-reasonable-price” (GARP) investor. The GARP approach, often characterised as a hybrid of growth and value investing strategies, is to look for companies delivering earnings growth that consistently outstrips the broader market, while excluding contenders that are on very high valuations.

If that sounds too good to be true, Lynch argues these businesses are waiting to be discovered – if you’re prepared to make the effort. “There are always pleasant surprises to be found in the stock market,” he says. “If you study 10 companies, you’ll find one for which the story is better than expected; if you study none, you’ll have the same success buying socks as you do in a poker game where you bet without looking at your cards.”

As for Lynch himself, years of making the effort enabled him to quit while he was ahead. Turning 46, the age at which his own father had died, Lynch decided he wanted to spend more time with his family and doing the things he loved. “When the operas outnumber the football games three to zero, you know there is something wrong with your life,” he observed, standing down from Magellan in mid-1990.

How to invest like Peter Lynch

Can you put Peter Lynch’s methods to work for yourself? Yes, argues Ben Yearsley, a director of Fairview Investing. “Simple observations can lead to interesting investments,” he says. “Is your favourite shop always busy? What about that company you use that’s just put its price up by 20% but you’re still using because it’s the best?”

There are several fund managers who are fans of the Lynch approach, Yearsley points out. “Lynch was more of a growth investor with a nod to value,” he says. “The obvious fund suite is the Artemis “smart GARP” range of funds - their emerging markets’ fund is particularly hot at the moment.”

Another possibility could be one of the two funds run by Nick Train, known as a bottom-up stock picker who looks for high-quality companies with strong long-term growth potential. The WS Lindsell Train UK Equity Acc fund and Finsbury Growth & Income Ord (LSE:FGT) Investment Trust aren’t run explicitly in accordance with GARP principles, but Train’s approach isn’t a million miles away.

- Watch our video interview: Nick Train: ‘the Americans have discovered Guinness!’

- Watch our video: Nick Train: ‘generational’ opportunity to buy UK growth firms

As for individual stocks, Richard Hunter, head of markets at ii, singles out two current contenders, based on PEG ratio analysis of the UK stock market.

“Airline easyJet (LSE:EZJ) has a PEG of 0.5 and is some 41% below its estimated fair value. The shares have fallen by 10% over the last year and by 52% over the last five, but the group is starting to see additional benefits to its core profit on two fronts. Ancillary revenue, which includes the likes of customer payments for personally allocated seats, baggage and food has been a success. In addition, and from a standing start, the group’s holidays unit recently reported a gain of 39% in the latest quarter to record a profit of £43 million, while being 93% sold for the first half of this year.

“The second stock is Prudential (LSE:PRU), which has a PEG of 0.3 and is 60% below estimated fair value. The shares have also been under pressure, with a decline of 14% over the last year and 50% over the last five. The group has its eyes on the prize of the burgeoning wealth sector across both Asia, where it has long had an established presence and where prospects are not confined to China, and Africa.

“The group has previously estimated that with a combined population of around four billion, the addressable market is $1 trillion of additional annual gross written premiums by 2033.”

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.