How to indirectly invest in IPOs through investment trusts

Some collective funds offer exposure to IPOs, with the manager sorting the wheat from the chaff for you.

18th May 2021 11:41

by David Prosser from interactive investor

A number of collective funds offer exposure to IPOs, with the fund manager sorting the wheat from the chaff on your behalf.

Initial public offerings (IPOs) are back. There were no fewer than 20 new company listings on the London Stock Exchange during the first quarter of 2021, the strongest start to the year since 2007, according to consulting firm EY.

Other markets enjoyed a similar resurgence compared to 2020, when few companies wanted to float amid the Covid-19 uncertainty. PwC reports that global IPO issuance in the first quarter hit an all-time high.

Many retail investors are keen to join the party, as high-profile IPOs from well-known businesses continue. The brewer BrewDog, petrol stations company EG Group, cybersecurity specialist Darktrace and fintech darling Wise (formerly known as TransferWise) are among the firms expected to unveil flotations in the coming months.

- Find out more about IPOs on interactive investor here

- The 25 highest-yielding equity investment trusts revealed

- Investment trust tips: winners and losers so far in 2021

However, before you get excited about any IPO, ask yourself two questions: can I take part – and should I?

The first of those questions is a very real issue. Significant numbers of companies floating on the stock market opt for slimmed down IPOs aimed at institutional investors only. These new issues are less complicated and cheaper to organise, but retail investors cannot easily participate.

There is widespread frustration about such IPOs, particularly when businesses with large consumer followings go down this route; recent examples include footwear manufacturer Dr. Martens (LSE:DOCS) and the online card retailer Moonpig (LSE:MOON). Earlier this year, interactive investor, along with other platforms, wrote to the Treasury asking for an inquiry into how to prevent retail investors being disadvantaged in this way.

Still, even if you do have access to an IPO, you may be wise to pass on the opportunity; flotations are not sure-fire winners. Shares in some companies do rocket on the first day of dealings – Moonpig jumped 26% - which is one reason retail investors feel so aggrieved at missing out. But others perform much less well.

The standout recent example is Deliveroo (LSE:ROO), dubbed the “worst IPO in London’s history” by one analyst in the wake of last month’s flotation. Shares in the food delivery company ended their first day of dealings 26% down on the issue price; by mid-May, investors who bought at issue were 40% in the red.

Pick and choose, in other words. Analysis from the Financial Times suggests that over the four years to 2020, IPO stocks on the main London market achieved an average return of only 5.2% over the first month of trading. That’s not much of a return given the volatility of many companies following an IPO – and there were plenty of losers.

“There are lots of good quality companies seeking a stock market listing and which would likely make a decent long-term investment, but all opportunities should be judged on their own merits,” says Lee Wild, head of equity strategy at interactive investor. “As Deliveroo proved recently, and Aston Martin (LSE:AML) a few years ago, buying shares in an IPO does not always guarantee a quick profit.”

In which case, there may be a savvier way to play the IPO game. A number of collective funds offer exposure to the best IPOs, with the fund manager sorting the wheat from the chaff on your behalf. Such funds or investment trusts also often invest in the businesses coming to market well before they are ready to proceed to a flotation, during what can be the period of their evolution when they grow quickest.

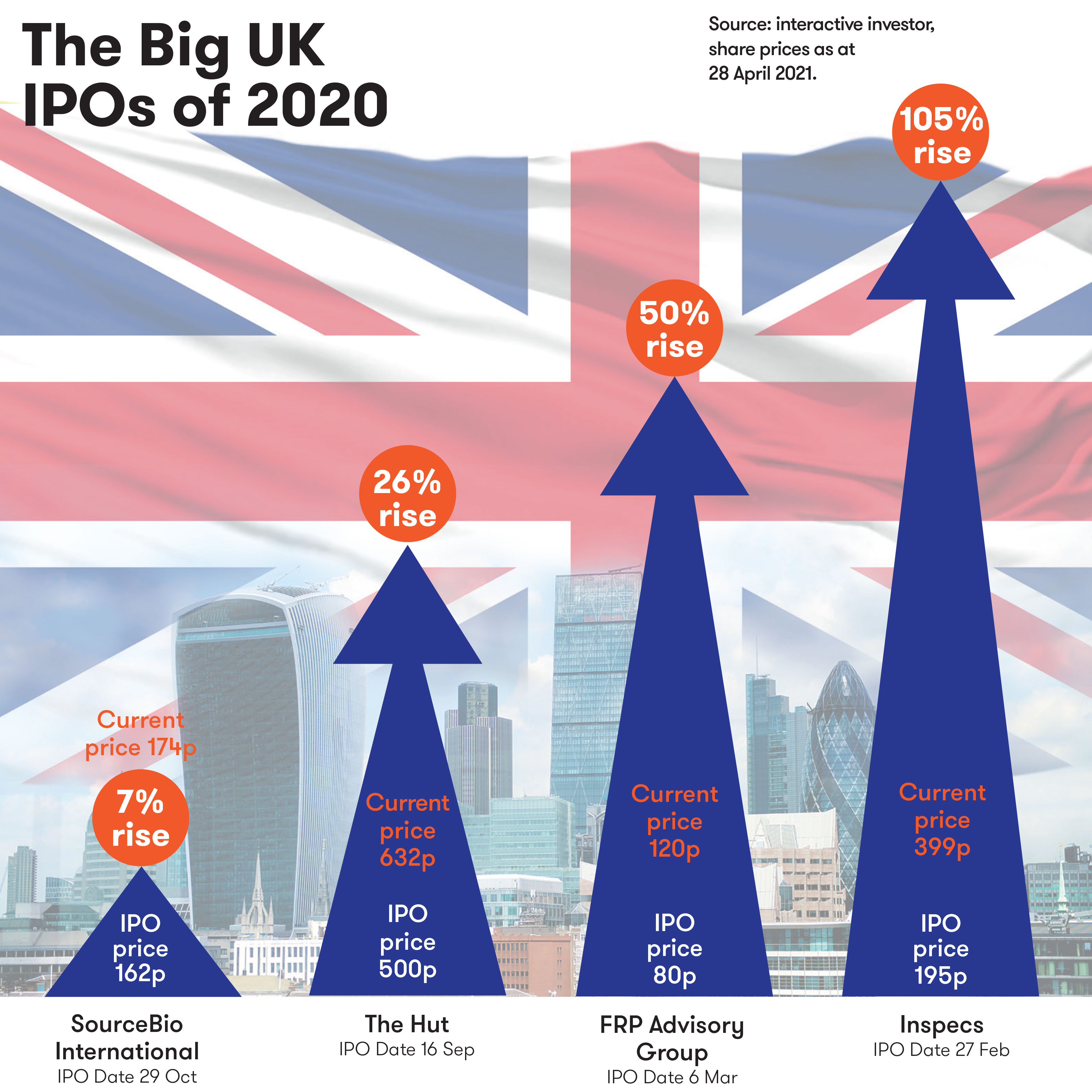

One such investment trust is Chrysalis Investments (LSE:MERI), run by Nick Williamson and Richard Watts of Merian Chrysalis, which is now owned by Jupiter Asset Management. Williamson and Watts take stakes in privately owned businesses potentially headed for an IPO, often investing additional funds during the flotation and retaining their stakes thereafter. The fund’s best-known holding is The Hut Group (LSE:THG), the e-commerce businesses that floated last September.

“Half our alpha [outperformance of the market as a whole] over the past five years has come from IPOs, but that comes from experience and understanding of how to value these companies,” says Williamson of Merian Chrysalis’s broader activities. “There are always areas of the market that get overvalued and hyped up; our job is to sift through the opportunities to identify those where the valuation is on our side.”

In practice, Williamson reckons his team has invested in somewhere between 10% and 20% of all the IPOs it has looked at over the past five years. Some companies have been ruled out because they fall outside the manager’s remit – it invests almost exclusively in small and medium-sized companies – but more often, Williamson and his colleagues have decided to steer clear for fundamental investment reasons.

That should give investors an idea of how many IPOs the professionals believe are really worth backing.

Moreover, the advantage of investing through a fund is that you get an experienced IPO investor running the slide rule over potential new issues on your behalf. A fund also gives you access to diversification benefits; even if it decides to participate in a flotation that bombs, the other companies in its portfolio provide insulation.

Chrysalis Investments is not the only investment trust that invests in both private and publicly listed companies in this way, including during IPO processes. The Association of Investment Companies’ Growth Capital sector, set up 18 months ago as a home for funds that specialise in taking non-controlling stakes in private companies, includes Schroder British Opportunities (LSE:SBO), Baillie Gifford-run Schiehallion (LSE:MNTN) and Schroder UK Public Private Trust (LSE:SUPP).

There are also plenty of funds that will include unlisted investments in portfolios that predominantly consist of listed securities. The top-performing Scottish Mortgage (LSE:SMT) is one obvious example from the investment trust sector, where the closed-ended fund structure is more appropriate for holding illiquid assets such as unquoted companies.

If you do prefer an open-ended fund, Baillie Gifford Pacific is one to consider for the growing number of IPOs taking place in the Asian region; it often takes unlisted holdings in its Pacific Horizon (LSE:PHI) investment trust vehicle and then subscribes to their IPOs in its open-ended alternative. “There are very good businesses to come through and there is a strong IPO pipeline,” says manager Ewan Markson-Brown of the year ahead.

Compared to retail investors confronted with a new IPO opportunity, these funds are well-placed to address the two fundamental questions tha all potential investors face in a business coming to the market for the first time: is it a business with strong growth prospects ahead of it; and even if there is a positive story to tell in this regard, are shares in the business being offered at a reasonable price? Market perceptions of whether the valuation is fair, particularly in the shorter term, will be a crucial driver of post-IPO performance.

- Read more of our content on funds and trusts here

- Take control of your retirement planning with our award-winning, low-cost Self-Invested Personal Pension (SIPP)

Given these complexities, Darius McDermott, the managing director of FundCalibre, the fund ratings agency, is a fan of the collective investment route into IPOs – and an investor in Chrysalis.

“Many companies are now staying private for longer because it is relatively easy to raise capital and because a stock market listing comes with certain disadvantages,” he says. “Funds can offer a way into those businesses well before an IPO and they spend all their time talking to companies at this stage of their evolution, so when it comes to a flotation, they know them well.”

This is not to suggest investors should never take part in an IPO. McDermott’s tip is to think hard about the business’s motivation for listing as you weigh up whether its shares offer fair value. “What are the business owners looking for – a way to take a chunk of value out of the business they have built up, or investment to fund further growth?,” he says. “If it is the former, it is not unreasonable to think the IPO will be more aggressively priced.”

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.