Your essential guide to: the state pension and how the goalposts will shift in future

We demystify the complex rules applying to those reaching retirement age after 6 April 2016.

18th November 2019 11:15

by Ceri Jones from interactive investor

We demystify the complex rules applying to those reaching retirement age after 6 April 2016.

Like everything to do with pensions, the state pension is fiendishly complicated – and the goalposts keep moving.

In 2016, faced with escalating costs, the government decided to overhaul the system and introduce what it called a new ‘flat’ rate state pension. However, it is not in fact flat at all and depends on the national insurance (NI) record an individual builds up over their working life.

- Steve Webb's Pension Clinic

- Biggest pension regrets revealed and gender gap laid bare

Time sensitive

For those who had already reached retirement age on 6 April 2016, nothing has changed; but for everyone retiring after that date, the eligibility rules are more onerous. Under the new system, to get a full state pension requires 35 years of NI contributions, compared with 30 years previously. Moreover, you need to have made at least 10 years of NI contributions, otherwise you will receive nothing at all.

- Learn more: What is a SIPP? | ISA vs SIPP | SIPP Tax Relief Explained

The full state pension rate is £168.60, so for example if you have accumulated 10 years of NI contributions, you’ll be paid 10/35ths of the total, or around £48 a week.

A rough guide to how much state pension you’ll get is to multiply the number of years you’ve worked by £4.80 to calculate the weekly pension amount.

However, your ‘qualifying years’ of NI contributions are not only based on years in work but also take account of time spent raising children up to age 12, caring for someone who is sick or disabled, or in full-time training.

You are credited automatically if you are a parent registered for child benefit for a child under 12; but it has been estimated that around 200,000 families are effectively giving up their entitlements, because the higher earner is the partner registered for child benefit, when it would be more usefully registered to the partner staying at home to enable them to accrue state pension credits.

Grandparents under state retirement age who care for grandchildren under 12 years for 20 or more hours a week can also qualify for NI credits if the working parent donates the child benefit credits they receive.

You can check your national insurance record at gov.uk/check-national-insurance-record, which will list your contribution record on a year-by-year basis.

If your contribution record falls short, then you can pay voluntary NI contributions to plug the gaps. Similarly, people with fewer than 10 qualifying years may want to make voluntary contributions to bring their record up to the eligibility minimum.

These voluntary contributions are a good deal. Class 3 NI contributions cost £780 in this financial year and will boost your annual state pension by around £249.60 (52 weeks x £4.80). They must normally be paid within six years of the tax year to which they relate.

You can instead pay cheaper Class 2 NI contributions, but only if you are self-employed on low earnings, unemployed and not claiming benefits, or living abroad. These cost £156, which is even better value.

So far, so good, but there are additional complexities. In particular, under the old rules, employees were able to top up their state pension, firstly under the State Earnings Related Pension Scheme (Serps) and then under the Second State Pension (S2P). However, many people contracted out of this scheme in the late 1970s and 1980s because both they and their employer were allowed to pay slightly lower NI contributions if they did so.

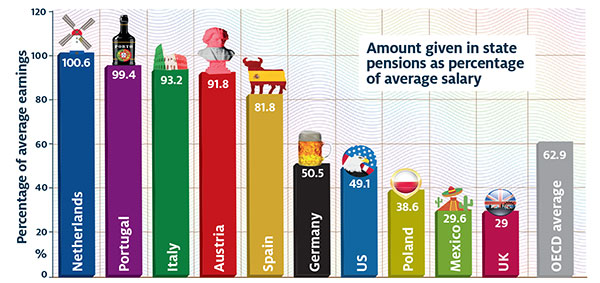

State pension national ratings

Source: Organisation for Economic Cooperation & Development, December 2017

Opt-out extension

Initially people could only opt out if they were members of a final salary scheme, but in 1988 the government extended this to defined contribution schemes, and for five years paid an extra 2% of the individual’s earnings into their personal pension as an incentive. This encouraged more than five million people to leave Serps for a personal pension over the next four years. When these individuals retire, they will typically receive less than the full state pension.

Unfortunately, it is not as simple as saying that each year they were contracted out amounts to a one-year deduction from their NI record. The Department for Work and Pensions tries to ensure it is fair by making individual reductions to state pensions – known as the Contracted Out Pension Equivalent or Cope – based on the extra funds it assumes people built up with the rebates they received when they contracted out, calculated according to its view of the investment returns that could have been achieved.

The Cope will show on your state pension forecast as the amount of additional State pension you would have received, had you not contracted out. The part of your private pension earmarked as having been created by these NI rebates is called the Guaranteed Minimum Pension (GMP) and is the amount the private pension scheme has to pay you if you contracted out.

For those who continued to top up their state pension in good faith by contributing to Serps and S2P, the government has promised to pay the better of the amount they would have received under the new and old systems. Serps was the more generous of the two top-up schemes and as it was abolished nearly 20 years ago, fewer people over time will be better off under the old system than the new one.

Finally, it’s important to know that the state pension is not paid automatically – you have to claim it. Around two months before you reach state pension age, the government’s Pension Service will send you a letter telling you how to do this.

You can defer claiming your state pension, which may be useful if you’re still working. For every nine weeks you defer, your weekly state pension will rise by 1%, or for a year’s deferral it will rise by 5.8% (amounting to an extra £9.78 per week for life). Go to gov.uk/deferring-state-pension.

-Steve Webb: state pension deferment could make financial sense

State pension ages

As everyone who reads a newspaper will know, the state pension age is being raised to 66 for men and women by April 2020, then to 67 by 2029, with a further rise to 68 between 2037 and 2039. It is likely to climb again to 69 in the 2040s and 70 by the mid-2050s.

Campaign group WASPI (Women Against State Pension Inequality) has argued that the pace of the rise for women has not allowed sufficient time to make other provision for retirement, but the government has refused to make any concessions.

The Liberal Democrats have, however, pledged to help, and there have been suggestions of a one-off payment of £15,000 to women born in the 1950s.

Sustainability in the medium term

The state pension is funded like a bank current account, with money coming in as NI contributions and being paid out as state pensions. However, as life expectancy has soared, the system has become unsustainable.

In 1942, when the Beveridge Report laid the foundations for the basic state pension, life expectancy for a man was just 63, while today it is about 80. Currently, there are 1,000 workers to every 310 pensioners, but by 2036 the ratio is projected to be 1,000 workers supporting 360 pensioners.

Even the Government Actuary’s Department says funding for state pensions will run out by 2032; yet the UK has the least generous state pension of any developed economy in the world, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (see graph), so not much can be done to scale down benefits.

One response would be to abolish the triple-lock guarantee, which promises state pensions will grow each year by the highest of inflation, average earnings or a minimum of 2.5%.

This is an intergenerational fairness issue, as younger working people are paying for the inflated annual increases of pensioners, leading the House of Lords Intergenerational Fairness and Provision Committee to recommend the triple lock be removed and the state pension uprated in line with average earnings to ensure parity.

The main political parties have committed to keeping the triple lock until at least 2020, pushing the problem into the long grass.

The elephant in the room is means-testing. This could be seen as a betrayal for workers who made NI contributions for decades on the basis it would pay them an income in retirement, and is much more likely under a Labour government, which might divert funds to those it thinks need it more.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.