Would a sea change in style scupper your portfolio?

Why investment trust investors should consider a tilt towards value strategies.

7th May 2021 16:53

Why investment trust investors should consider a tilt towards value strategies.

This content is provided by Kepler Trust Intelligence, an investment trust focused website for private and professional investors. Kepler Trust Intelligence is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. It is provided for information only and does not constitute a personal recommendation.

Material produced by Kepler Trust Intelligence should be considered a marketing communication, and is not independent research.

‘Quality’ investing styles have enjoyed structural tailwinds for around 40 years. Over this period, cyclical variances have happened, but the trend towards bigger companies, increased concentration, greater ease of movement of capital across borders, and economies of scale has ultimately always prevailed. Quality has consistently won out. As we discuss below, the improvement to the relative return profile of quality factor investments has been greater than any other, while value as a style has struggled relative to all others.

We think the structural backdrop which caused this may be in the process of reversal; more to the point, even if it does not reverse but merely stays in stasis, we think fundamental pathologies to market structure means investors should consider building some protection against a shift in the dominant style into their portfolios. In other words, it would be dangerous to assume that the recent value rally is just a temporary phenomenon that we will shortly be able to forget about.

Thinking past the last low

On 30 September 1981, US nominal 10-year bond yields hit 15.84% (Source: St Louis Federal Reserve). If you were a young entrant to the market place at that time, say 21 years old and starting out a career in finance, you would now be 60-61 years old. In other words, there are probably not too many remaining practitioners in financial markets who remember a time when the generalised trend for probably the most important yield in the world was higher (albeit it presumably did not feel like the corner had been turned at the time).

Falling yields on safe haven assets are one of the structural features of almost all investors’ careers at this point. Globalisation is another. The work of Daniel Kahnemansuggests that most of us exhibit biases in how we interpret information, perceiving a flow of information within the context of pre-existing patterns and frameworks. In some cases, some of us became temporarily acutely aware of this as lockdown policies eased when we first turned up to the pub without our wallet (or, indeed, trousers). With most market participants having operated in a trend pointing one way for the entirety of their careers, clearly we are likely to interpret new informational flows in line with this framework.

Despite your analyst’s last visit to the GP confirming his biological age “should qualify him for a free bus pass”, by the strict ‘passage of time’ measure the government insists on using in ascertaining age, I too have not experienced a sustained bear-market in bonds, as with most readers. We will, accordingly, be inherently disposed to treat any challenges to this model and structural trend as temporary setbacks, whilst supportive news-flow will be confirmation. Similarly, it may be tempting to view the increased focus on national, as opposed to international, solutions during the pandemic as a transitory phenomenon, and the inflation surrounding the exit from the pandemic as the same.

The recent ‘value’ rally seems, from most commentary, to be largely seen as a cyclical phenomenon, a reflection of a likely economic upswing from an extreme economic shock against a backdrop of rapidly diminishing spare capacity and significant stimulus. In many instances, it has also served as a reappraisal of the fundamental solvency/longevity of many ‘old-economy’ companies; markets do not necessarily believe these companies suddenly have a bright future, merely that economies reopening prolongs their lifespan.

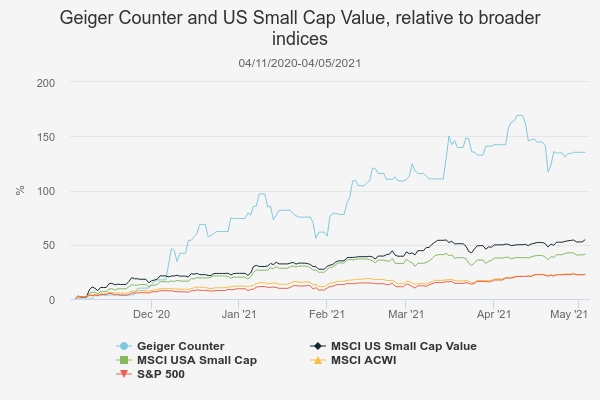

Those suggesting this rotation is merely the start of a bigger structural shift in the operating backdrop, such as the managers of the Ruffer Investment Company (LSE:RICA) seem, anecdotally, to be relatively few in number, but do also seem to be growing. Yet if it is a secular shift, and if investors are structurally positioned for a continuation of the recent market environment, there could be major investment implications. In fact, particularly given the market structure encourages crowding and momentum trades, we think there are convex opportunities to protect against such an environment. Illiquid areas of the market, especially those which are outwith the scope of passive vehicles, have, in many instances, seen huge squeezes higher on even minor increases in marginal buying pressure. We have seen this, for example, in uranium mining companies in recent months. Shunned for the past decade by the vast majority of the market, relatively minor newsflow (starting with suggestions the US would extend the life of its nuclear fleet; no new capacity, simply a longer lifetime) has triggered an extremely sharp rally. We have shown this via the performance of the Geiger Counter (LSE:GCL) investment trust below, and of US small-cap value.

GEIGER COUNTER AND US SMALL CAP VALUE: PERFORMANCE OVER PREVIOUS SIX MONTHS

Source: Morningstar. Past performance is not a reliable guide to future returns

Price is what you subcontract, value is what you extract

At the present time, investors may be evaluating the short- and medium-term outlook for cyclical inflationary pressures or economic slippage. Yet we think the potential for a structural shift merits attention too.

Although low and falling interest rates have helped quality strategies, we would argue the signing of the Uruguayan round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1994 was more important for their ascendancy, along with the establishment of the World Trade Organisation in 1995. These innovations massively eased the flow of services, capital, and intellectual property (amongst the most important areas), which made it easier to grow brands internationally.

As a result, existing moats were strengthened further in ‘quality’ companies as they were able to leverage strong domestic positions into strong global leadership.

Stock prices should typically reflect the market’s expectations for the discounted lifetime cashflows of that company. Surprises relative to these expectations cause adjustments in the share price. Quality’s outperformance has been a reflection of the surprising ability to squeeze ever more marginal gains out of the freedoms afforded them by the global economic system.

Large multi-nationals have, in recent decades, been able to shift manufacturing bases to take advantage of lower regulatory and labour costs without any of the previous costs or impediments to importing these goods to their home countries. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage has been taken to extremes in dispersion of supply chain inputs; take the typical supply-chain for semiconductors, that essential glue to modern industry and technology. Intellectual property primarily derived from US institutes is produced largely in Taiwan (and, to a lesser extent, South Korea), using machines typically built in Japan and Europe, with raw materials from the US which have been processed in Japan or Korea, and are then put to practical use through assembly/insertion into end products in China. The more labour-intensive aspects can be outsourced to low-wage jurisdictions, whilst specialist elements remain rooted in more developed countries. And semiconductors are a mere component, not even in themselves a final product for delivery to the end consumer.

Efficiency within a company is getting more productive capacity and output for less cost inputs. Prior to the establishment of the WTO, there were greater impediments to bringing overseas production back to developed consumers in the form of finished goods. Absent these challenges, the relative advantages of employing in greater numbers (but with lower costs per worker) via offshoring when compared to purchasing new machinery (for greater output per worker) rose. Borrowing again from Ricardo, this time from his ‘labour theory of value’, this increase in cost control on the side of labour can drive profit expansion without the same deployment of strategic leverage to fund capex (yet aggregate corporate indebtedness, and the share of ‘zombie companies’ has soared).

Calling the rain

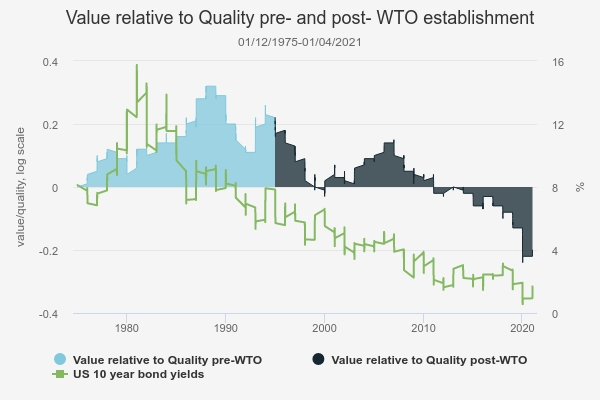

We would argue that the fact bond yields had been declining for many years prior to 1994 whilst value continued to outperform (see graph below) means trade liberalisation has been the more important factor behind quality outperforming. We suggest quality outperformance reflected operational developments favouring large multi-nationals with wide moats, whose operational outperformance were themselves disinflationary, ensuring they could better restrain end consumer pricing increases and thus increase market share whilst expanding margins by cutting input costs (proving a tailwind for bonds). In other words, the impact of offshoring in part helped drive the structural lowering of rates and bond yields after these trade liberalisations.

Below we can see the sharp reversal in fortunes in the global value factor index relative to quality from 01/01/1995, when the WTO was launched. Over history we have seen cycles beforehand favouring either style, but this marked a shift to nearly continual quality outperformance. Markets are, of course, discounting mechanisms, and the Uruguayan round of the GATT talks went on for several years beforehand. We have used a log scale to remove exponential biases from extended trends.

VALUE RELATIVE TO QUALITY, PRE- AND POST- ESTABLISHMENT OF WTO

Source: Morningstar, St Louis Federal Reserve. Past performance is not a reliable guide to future returns

Similarly, if quality outperformance were solely a function of falling rates expectations, we might reasonably expect to see just as great, if not more so, a rotation in favour of growth strategies as quality. After all, growth companies benefit from lowered discount rates, from presumed greater ease of funding and from rising duration.

In the table below, we can see the median rolling 12-month returns of quality relative to growth and value factor indices both pre- and post-WTO ratification, and growth relative to value. We can also see how often quality outperformed value and growth pre- and post-WTO ratification, and the performance of growth relative to value. Quality has been the clear winner in the post-WTO environment.

QUALITY ROLLING 12-MONTH RETURNS RELATIVE TO VALUE AND GROWTH, AND GROWTH RELATIVE TO VALUE

| MEDIAN RELATIVE RETURNS | MEDIAN RETURNS PRE-WTO | MEDIAN RETURNS POST-WTO | DIFFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth relative to Value | -2.66 | 1.14 | 3.8 |

| Quality relative to Value | -4.13 | 5.4 | 9.53 |

| Quality relative to Growth | 0.85 | 1.71 | 0.86 |

| % occasions outperformed | Pre-WTO | Post-WTO | Difference |

| Growth outperformed Value | 28.6 | 57.3 | 28.71 |

| Quality outperformed Value | 37.8 | 69.3 | 31.52 |

| Quality outperformed Growth | 54.8 | 65.5 | 10.67 |

Source: Morningstar 01/12/1975-01/04/2021 Past performance is not a reliable guide to future returns

And once you're gone, you can't come back(?)

Clearly if the structural tailwinds become headwinds, this has important ramifications for the performance of quality. This doesn’t mean that quality is a worthless strategy. It offers stability, while the crowding driven by passives and investor bias offers greater potential upside in extreme scenarios. Combining the two strategies in a portfolio means investors can be prepared for shifting market environments.

We think, however, it may be time to tilt more towards value strategies and set out further below some evidence that we think suggests there is some reversal in these trends that have driven value underperformance ongoing. However, mere stagnation at the current state of affairs will impact future dynamics. If globalisation has merely reached saturation point and the diversification and specialisation of supply chains has reached its maximum extent, the ability to leverage this to positive surprises relative to expectations will likely negatively impact the performance of quality stocks. In fact, we think recency bias may lead investors to overlook the evidence that a structural shift away from ever increasing globalisation could be imminent.

Janet Yellen, US Treasury Secretary and former Fed chairwoman, recently called for a global minimum corporate tax rate. This was met with receptiveness in many seats of power. Scepticism abounds, but what we would contend matters is not necessarily whether it is successful at this time, but what it tells us about the direction of travel.

The relationship of China to the West is fundamentally altered. This is not a sudden rupture, but the flow is likely to one way. An assumption that costs previously outsourced to China will simply be relocated to other low-cost hubs might be fair. However, it ignores Chinese assertiveness on the world stage and the likely increasing bifurcation into aligned blocs (and convenient middle-parties, with India, Russia and Turkey likely prominent amongst the latter). Meanwhile, the EU has made clear it is re-evaluating ‘strategic dependencies’, with a view to bringing supply chains closer to home.

It is not only in trade relationships, however, that we are starting to see re-alignment. Politically, we have seen seismic shifts. Canny politicians increasingly suggest that voting constituencies are less focussed on aggregated GDP than on a mixture of tangible big-issue matters and localised economic health. Generational issues also seem at play; younger, influential, political players, from Hawley and Cotton in the Republicans to Cortez and Yang within the Democrats, are focussing on structural challenges they perceive, often in alignment on the nature of the problems despite approaching from entirely different perspectives.

We’re going to need a bigger moat

Antitrust is perhaps amongst the most tangible and important potential shifts in the dynamics of surprises intra-market, and the recent appointment of Lina Khan to Commissioner on the Federal Trade Commission (and her approving reception by most Republicans) seems a pretty clear signal of the direction of travel. And now, all of a sudden, steel tariffs have been deemed of strategic importance, with bipartisan support.

Political ructions running contrary to the political orthodoxy have become more frequent in recent years, whether it be Trump’s victory in 2016, Syriza forming a Greek government, Le Pen putting in a credible challenge for the French presidency (indeed, Macron’s successful run from outwith the party system perhaps also fulfils this criteria), the ascendance of Modi, the death of Forza Italia and the PD, and rise of the Lega, Five Star Movement and Brothers of Italy in their place, the poll-lead of the Greens in Germany, Brexit, Obrador in Mexico or Bolsonaro in Brazil. Systems are being challenged. These are disparate forces, but scepticism of the societal impact of ever-expanding globalisation are common themes. A return of income, whether it be via ‘bringing jobs home’, ‘a green new deal’, or others, also runs commonly throughout.

Small wonder, perhaps, that populations are restive when the labour share of GDP has declined in most of these countries since 1991, the fall of the Soviet Union and ‘the end of history’ (rejoice, citizens of the UK. Along with France, but otherwise alone amongst G7 economies, ours has marginally risen over this period).

Perhaps this is why we are starting to see more wage inflation pressures; as Gavekal highlight, the Covid-19 recession was unusual in seeing wage growth unaffected; there is a different zeitgeist in the air when compared to the 2008/09 great financial crash. By contrast, as the Wall Street Journal has noted, in tough conditions during 2009 US companies cut 5.3% of their workers in the US, and 1.5% of those abroad[4]; firms cut higher wages to maintain lower ones and profit margins.

We have seen an environment of increased corporate concentration since the WTO formed, and the financial sector has not been immune. Despite access to basic financial metrics, markets can tend to extrapolate historic operational challenges faced by industries and specific businesses out eternally (particularly with the increasing incorporation of algorithmic filtering systems). Value strategies typically have had to rebrand as boutique, niche, or ‘guardians of the flame’ type strategy, fighting the good fight against a market that at times seems not to care what price it pays.

A multitude of factors (from reshoring, inflationary pressure, antitrust, re-evaluation of strategic imperatives) look, to us, to be potential tailwinds to value strategies globally relative to their peers. However, as an investor, the possibility or probability of all materialising is not relevant, merely sufficient a shift in dynamics (even a state of stasis) so as to force markets to readjust their future expectations.

Cry Havoc

The Miton UK Microcap (LSE:MINI) trust was launched with the expectation of a seismic shift in the dynamics of globalisation in mind, and the investment process aims to be aligned with much of what we have set out above. The manager believes that we are already amidst a stalling and/or reversal of the trends of globalisation and that moves to reshoring will create a virtuous cycle for incomes, smaller companies, inflationary pressures, and value strategies. As supply chains shorten, the aggregated bargaining power of labour rises, and income inflationary pressures rise. The increase in marginal capacity to choose in spending creates the potential for much more extended cycle and exponential challenges to the marginal positive surprises of quality strategies. His portfolio and strategy specifically look for under-researched and undervalued stock where there are catalysts in the near-term future to drive significant cash returns.

Then spring became the summer

The shoe has very much been on the foot of dominant buyers in Western economies as economies of scale have won out. However, inflation in raw materials will prove hard to offset, especially whilst supply discipline remains within the sector and when the private sector is increasingly competing with governments. Moreover, many firms further up supply chains are in essence at the subsistence level; reliant on the goodwill of their dominant buyer to give them a good enough price to keep the lights on. It is simply not tenable for these suppliers to absorb increased input costs on raw materials.

Countries which are suppliers of raw materials will benefit from improving terms of trade, as we have previously highlighted. Even if there remains some ‘wiggle-room’ to continue to relocate a widget factory, for example, to a lower cost jurisdiction, materials largely have to be produced where they are. The recent Greenlandic election pointed to the tensions for raw materials that will become systematic, with the US interested in accessing Greenland’s supply of rare earth metals (whilst China is also interested, seeking to protect its dominance in this market).

Latin America, with positive sensitivity to rising commodity prices and falling within the Monroe doctrine sphere of influence, stands out as having the potential to perform well. Valuations, we would suggest, most assuredly do not reflect this, as we have previously discussed. BlackRock Latin American (LSE:BRLA), offers exposure to this market, and is itself trading at a discount to NAV of circa 11.4% (as at 29/04/2021).

Markets where quality may yet win out

Nominally, a move towards structurally higher inflationary pressures should be bullish for European stocks, at least on a relative basis to US stocks, and particularly so for European value stocks. Such a reflationary environment should reduce insolvency concerns, which stalk the corporate zombie-infested Eurozone economy. However, the inability of the Eurozone economy to rebalance in the same fashion, as companies can still arbitrage costs across member states, mitigates any benefits. Germany’s seemingly structural trade surplus is not a sign of economic strength, but of weakness; it represents an inability of the economy to rebalance towards consumption when it has an undervalued exchange rate.

Undoubtedly, European ‘value’ has tactical upside beta if the global recovery accelerates, but without resolution of these fundamental pathologies it is hard to see Eurozone banks, for example, as anything other than long-term value traps. Appeals to consider only the companies and not the locale of listing have some merit, as the structural inertia in these economies means there are unlikely to be competitors with the dynamism arising to take the place of the structural winners of the previous 30 years.

However, geographically we think investors with a ‘yen’ for quality [that’s enough – Ed] investing styles are best placed to look to Japan. Japan retains a highly fragmented corporate market, ripe for consolidation. In deference to social stability, impairments have been quietly absorbed by the corporate sector en-masse to ensure employment remained high and wages reasonable relative to the cost of living over the past 30 years. There is, frankly, room for pushback by the corporate sector, and we can observe very easily clear measures put in place to incentivise improvements to shareholder returns in recent years.

Reifer and Atherton of Man GLG have recently highlighted an unusual valuation anomaly within the Japanese market. Government regulations now push listed companies to achieve a return on equity of at least 8%. For those that do not over three consecutive years, shareholders are encouraged to remove the board. As a result, firms meeting this 8% ROE target enjoy sharp valuation premiums to other companies. In most markets, the relationship is relatively linear. In Japan, it is convex, as a result of regulation. Quality companies are being actively incentivised in a market ripe for consolidation and margin expansion. Blending valuation and quality considerations, the Coupland Cardiff Japan Income & Growth trust (CCJI) could, we think, be well placed to benefit. CCJI last reported portfolio level ROE in excess of this 8% level, but hunts in grounds where substantial valuation uplift seems not only feasible but plausible.

Similarly, AVI Japan Opportunity (LSE:AJOT) focuses on fundamentally high-quality businesses with substantial valuation discounts. As this strategy also utilises active engagement to achieve goals, successful engagement strategies could have disproportionate success when married to wider market re-appraisal in our view. In the meantime, in a fractious and uncertain world, these companies offer substantial margins of safety.

Conclusion

“Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM”, as the old investment saying used to go. Nobody would blink an eye at buying the FAANGs now, for example. And the fact is, many of these companies enjoy premium status because they are extremely well-run companies with highly attractive goods, services and products. However, it is hard to argue this is not now reflected in the price.

What matters now for ‘quality’ investment strategies is not whether we are at some seismic shift in structure. It is whether it is really tenable to support the idea that continuous positive adjustments can be expected from those factors which have driven quality outperformance.

Cyclical tailwinds to value investing styles certainly exist. Whether they convert to a structurally improved market environment likely depends on whether feedback loops start to generate, reversing the structure. However, the perversion of market structure by the invasive creep of the passive overhang means that convex opportunities by seeking out off-benchmark, under-appreciated value areas of the market should remain, and not holding exposure to these areas could prove costly.

The sands seem, in any event, to be shifting. The Overton window in global geopolitics has shifted, and benign assumptions of the global brotherhood of nations in a post-ideological world are shifting into the rear-view mirror. End markets, production facilities, raw materials, and strategic imperatives will all count against some of the seemingly embedded ‘quality’ winners.

We don’t believe markets are ready for this. Market movements suggest that most struggle to believe that these are anything more than transitory difficulties in a linear progression. This is understandable; for the majority of market participants, such a trend will have been relatively ever-present over their investing careers. Yet history respects no ones’ lived experience, and longer-term frameworks place the most recent epoch as just one of many long-cycle variations.

Kepler Partners is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. Neither Kepler Partners or interactive investor will be responsible for any losses that may be incurred as a result of a trading idea.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Important Information

Kepler Partners is not authorised to make recommendations to Retail Clients. This report is based on factual information only, and is solely for information purposes only and any views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment.

This report has been issued by Kepler Partners LLP solely for information purposes only and the views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment. If you are unclear about any of the information on this website or its suitability for you, please contact your financial or tax adviser, or an independent financial or tax adviser before making any investment or financial decisions.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. The information in this website is not for distribution to and does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy any securities in the United States of America to or for the benefit of US Persons.

This is a marketing document, should be considered non-independent research and is subject to the rules in COBS 12.3 relating to such research. It has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research.

No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not to be taken as advice to take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm's internal rules. A copy of the firm's conflict of interest policy is available on request.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

PLEASE SEE ALSO OUR TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Kepler Partners LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales at 9/10 Savile Row, London W1S 3PF with registered number OC334771.

Kepler Partners LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.