Winners, losers and unintended consequences from QE experiment

A decade ago, quantitative easing saw central banks pump cash into the financial system; it may have ave…

12th June 2019 14:01

by David Prosser from interactive investor

A decade ago, quantitative easing saw central banks pump cash into the financial system; it may have averted a deep slump, but what have been the consequences for savers and investors?

Further rate cuts in bank rate alone might not be enough to bring inflation in line… the Bank of England remains committed to improving liquidity in credit markets that are not functionally normally.” So wrote Mervyn King, then governor of the Bank of England, to Alistair Darling, the chancellor of the exchequer, in March 2009. A decade later, the fallout from that letter is still being felt by ordinary Britons up and down the country.

King’s letter sought permission for the Bank to embark on a radical economic experiment that would be dubbed quantitative easing (QE). A version of QE had helped the US escape the Great Depression of the 1930s and also boosted the moribund Japanese economy in the early 2000s. With conventional monetary policy having failed to lift the UK out of the financial crisis-induced recession that had begun 15 months earlier – and having run out of road with official bank rates already cut to just 0.5% – the governor wanted to try something different.

The chancellor gave his permission. The Bank’s plan was to print new money that it would spend buying up gilts and high-quality corporate bonds held by the banking sector. By getting cash into the banks’ reserves, it hoped to encourage them to lend more to both corporate and personal customers, who would then spend and invest more, thereby stimulating the economy.

- Innovative Finance Isas: don’t let rewards blind you to the risks

Rising bond prices

All that cash going into the bond market would also push up the price of bonds, simultaneously bringing down yields. With interest rates across the economy set in relation to gilt yields, this would put further downwards pressure on borrowing costs, providing the economy with an additional shot in the arm.

In fact, the post-financial crisis QE experiment had begun in the US in November 2008, when the US Federal Reserve under Ben Bernanke began buying up mortgage-backed securities; by 2014, when the Fed halted bond purchases, it had acquired $4.5 trillion (£3.4 trillion) worth of assets. In the UK, meanwhile, the Bank of England’s QE programme got under way within days of the governor’s exchange of letters with the chancellor. The Bank’s purchases of gilts and higher-quality corporate bonds would eventually total £445 billion, including a £70 billion round of QE in 2016 following the UK’s referendum vote to leave the European Union.

Did QE work? Well, on the face of it, the Bank’s experiment proved successful. The UK came out of recession in the third quarter of 2009 and has since enjoyed a longer period of sustained economic growth than any other G7 nation. Unemployment peaked at much lower levels than in other countries and the recovery has seen employment hit record highs.

- How to build a core and satellite investment trust portfolio

Bravery vindicated?

Certainly, those involved in the decision to unleash QE a decade ago believe their bravery has been vindicated. David Blanchflower, a member of the Bank’s monetary policy committee at the time, said earlier this year: “It was the equivalent of 10,000 Warren Buffetts showing up… two people saved the world – Bernanke saved the world on the monetary front, and Gordon Brown on the fiscal front.” The current bank governor, Mark Carney, continues to praise the initiative.

Still, not everyone is convinced. Rob Macquarie of the think tank and campaign group Positive Money argues that QE has had little direct effect on large parts of the economy. Rather, he maintains, the rich have got richer, courtesy of asset price bubbles in markets such as bonds, equities and property as the Bank’s cash worked its way through the system.

“Bank lending to non-financial businesses has hardly increased since the crisis,” Macquarie says. “Instead, most of the new money has remained in financial markets, exacerbating a concentration of wealth in the south east of the UK and among wealthier households. Mortgage lending has resumed its steady climb. House prices, especially in London, are increasingly unaffordable.”

If that sounds uncomfortably political, other critics of QE go much further. Baroness Ros Altmann, the economist and pensions campaigner who served as pensions minister in David Cameron’s government, says QE is partly to blame for the unprecedented political volatility we have experienced in recent years.

“I believe unconventional monetary policies may have played a role in Brexit, Trump and rising populism, and the side effects may be feeding popular disaffection with the entire capitalist system – most particularly among the younger generation,” Altmann argues. “The powerful groups who benefit most from QE – governments, financial market participants and the wealthiest – have so far held sway, but ongoing redistribution may at least partly explain disaffection with the establishment and the rise of populism.”

The data does lend weight to this theory. The Bank of England’s own analysis, published last year, suggests the wealth of the average household in the richest 10% of the UK has increased by more than £350,000 during a decade of QE. Other groups in society have not kept pace. The Office for National Statistics calculates that the UK’s “Gini coefficient”, a widely used measure of inequality, rose 10 percentage points between 2010 and 2016.

QE, in other words, appears to have pitted rich against poor. It has also created a generational divide, since people over the age of 45 in the UK own 80% of the financial assets buoyed by the cash injection.

Turn to unintended consequences, and the granular detail of market performance over a decade of QE is remarkable. For savers with cash in bank and building society savings accounts, the depressive effect of QE on their returns has proved devastating. In December 2009, the average cash individual savings account paid an annual interest rate of 4.5% a year; by the end of last year, that figure had fallen to just 0.9%.

The introduction of QE was disastrous for savers,” says Anna Bowes, co-founder of website Savings Champion. “Savings providers no longer needed to attract cash from savers as they had access to cheap funding; this meant that best-buy rates dropped heavily to discourage savers, leaving old accounts paying comparably high rates – and these were therefore cut too.”

- What you need to look at before investing in a tracker fund or ETF

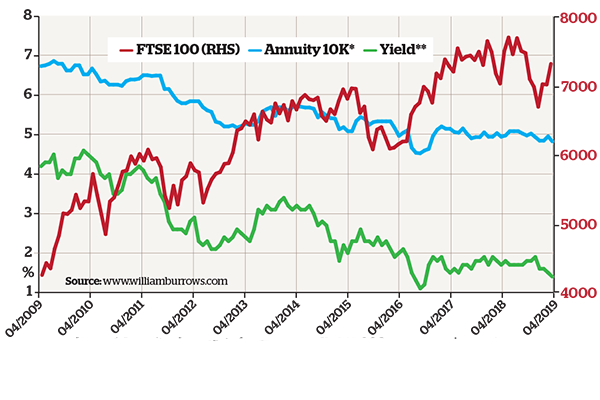

Shares soar; gilt yields and annuities slump

Notes: * Annuity shows rate for man aged 65, £10,000 purchase, single life and level payments. ** Yield shows 15-year gilt yield. Source: williamburrows.com

Better for borrowers

There has been better news for borrowers, with mortgage costs having fallen sharply alongside savings rates. The average fixed-rate mortgage deal has come down from above 6% in early 2009 to about 1.7% today. Still, while that will have been welcomed by many borrowers, it’s worth pointing out that first-time buyers have not necessarily benefited. As the average house price in the UK rose from £154,452 in March 2009 to £226,234 a decade later – a whacking 47% gain – many have simply been priced out of the market.

Meanwhile, more risky assets – generally the preserve of richer and older Britons – have soared in value. The FTSE 100 index of blue-chip equities dipped below 3,850 in March 2009 as investors fled risky assets in the face of recession and financial collapse; by March 2019 it was above 7,400, closing in on a 100% gain. Bond markets have returned average annualised returns of around 3.5% over the same period, a remarkably strong performance from what is supposed to be a low-risk, low-return asset.

Investors with holdings in these assets will be delighted with the returns they have earned. However, Jason Hollands, managing direct of Tilney Investment Management, warns that danger lies ahead because QE has effectively distorted the marketplace. “One distortion has been high levels of correlation across asset classes, which has broken down some of the traditional benefits of diversification,” Hollands warns. “As QE is withdrawn, this presents the very real problem of a potentially synchronised downturn in both equities and bonds, with few places to hide.”

What I learned when I met two financial planners

Forgotten about bear markets

That will take many investors by surprise, Hollands adds, because people have forgotten what a bear market looks like. “By helping underpin the longest bull market in history, QE has made many investors way too sanguine about risk,” he says. “Until last year, many investors had never endured annual losses on their investments; but beyond the decade of QE, down years for markets are actually quite common and should be expected.”

It’s also worth considering the effect of QE on pension savers, where this period of remarkable monetary policy has also had a profound impact. Savers accumulating pension assets in preparation for retirement will have benefited from the strength of bond and equity markets, but there is a problem. The cost of an annuity, which large numbers of savers still use to convert their savings into guaranteed pension income during retirement, has soared because of QE.

This is because annuity rates are typically set with reference to gilt yields. Since these have fallen to historic lows courtesy of QE, so too have annuity rates. Roughly speaking, a £100,000 pension fund would have bought a 65-year-old man an annual income of £7,850 in 2008; 10 years later, the same fund would have secured a pension of just £5,480. That’s almost a third less.

This is one reason why such large numbers of savers have taken advantage of the pension freedom reforms, opting to draw down an income directly from their pension funds, rather than buy an annuity. Bear in mind, however, that pension funds left invested in equities and bonds to generate that income are now at risk of the problems identified by Hollands. Pension savers with little long-term experience of financial market volatility may be in for a shock.

Even savers with defined benefit pension schemes run by their employers have not been immune from the effects of QE. The complicated formula used to calculate whether a final salary occupation pension fund has sufficient assets to meet the promises it has made to workers also depends on gilt yields. As a result, pension fund deficits have soared during the era of QE.

“Go back a couple of years and the total deficit on final salary pension schemes had ballooned to over £400 billion,” says Tom McPhail, head of pensions policy at Hargreaves Lansdown. “That’s an embarrassingly large shortfall between the cost of the promises made to employees and the amount of money available to meet them.”

While McPhail points out that deficits have eased over the past two years, employers sitting behind occupational schemes have come under intense pressure. Many have abandoned defined benefit schemes in the face of the rising cost of financing them, putting an end to further accrual of benefits for their members. Others have cut costs elsewhere in the business – on spending on wages and other benefits, for example – to try to get on top of deficits. In the most extreme cases, employers are going out of business because of the black hole in their pension schemes, jeopardising workers’ livelihoods today and their financial security in retirement.

Complicated consequences

All in all, what seemed 10 years ago to be an appealingly simple rescue remedy for economic misery – just printing more money to pump into the economy – has turned out to have remarkably complicated consequences. The UK may have avoided meltdown, but there has been plenty of collateral damage along the way.

One final thought. Will QE ever be unwound? While central banks still talk about moving towards qualitative tightening (QT), neither the UK nor the US – nor the European Central Bank, another QE enthusiast – has even begun the job. Even hints of QT to come have prompted market wobbles.

Baroness Altmann’s suspicion is that QT will never happen, with the Bank of England choosing instead simply to cancel the gilts and bonds it has bought without ever demanding repayment. “QE will then have resulted in a permanent redistribution of wealth and income, achieved via monetary policy, rather than the usual fiscal route and without the necessity of repaying all the accumulated past debts,” she says. “Only time will tell how history will judge this period.”

Winners and losers from the QE experiment

Five winners from QE

• ‘Risk-on’ investors, whose equity and bond holdings have been buoyed by the flow of central bank cash.

• Homeowners, for whom low interest rates and increased liquidity have reduced the cost of mortgage borrowing while raising the value of their properties.

• Passive fund managers, whose sales have soared in a marketplace where the rising tide of QE has pushed all equities upwards.

• Successive governments, which have been able to run up national debt to unprecedented levels without the UK going bust thanks to gilt yields that have sat at all-time lows.

• Donald Trump, Nigel Farage and their fellow populist politicians, whose support has increased on a wave of disaffection from non-wealthy voters angry about increasing inequality.

Five losers from QE

• Savers, who have suffered long periods of losing money in real terms on cash held in bank and building society accounts.

• First-time buyers, for whom cheap mortgages are less and less relevant with rising house prices moving the first rung on the property ladder ever higher.

• Credit card and overdraft borrowers, who are paying higher interest rates today for debt than 10 years ago, with banks seeking to increase profitability in this low-margin market environment.

• Pensioners, many of whom have locked into annuities at very low rates or opted for drawdown arrangements they are ill-equipped to manage.

• UK plc, which has had to cope with huge pension deficit volatility; many of the UK’s largest companies are now dwarfed by the size of their pension liabilities.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.