What to expect from the UK Budget

Labour’s first Budget is on 30 October. Tweaks to the treatment of Bank of England losses can create fiscal space, but material tax rises will be needed to satisfy the fiscal rules. This note surveys the economic landscape and potential tax rises.

24th September 2024 08:45

by Lizzy Galbraith, Luke Bartholomew and Paul Diggle from Aberdeen

A challenging fiscal environment The UK’s new Labour government faces a very challenging fiscal environment ahead of its first Budget on 30 October.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves has argued the government inherited a £22-billion “black hole” in the current fiscal year. While this is in part political narrative setting, some is the result of choices Labour has itself made around public sector pay settlements, which cost around £11 billion.

More fundamentally though, the medium-term fiscal outlook inherited from the previous government was built on implausible assumptions about the future path for real terms spending.

With Reeves set to keep the basic architecture of the existing fiscal rules in place, the binding constraint on fiscal policy is the requirement that government debt to GDP will be falling in five years. It is not yet clear by how much the existing fiscal plans fall short of this but estimates suggest it could be as much as £30 billion. This shortfall, which does not include reversing any of the planned real terms cuts to unprotected government spending, will need to be closed in the forthcoming budget.

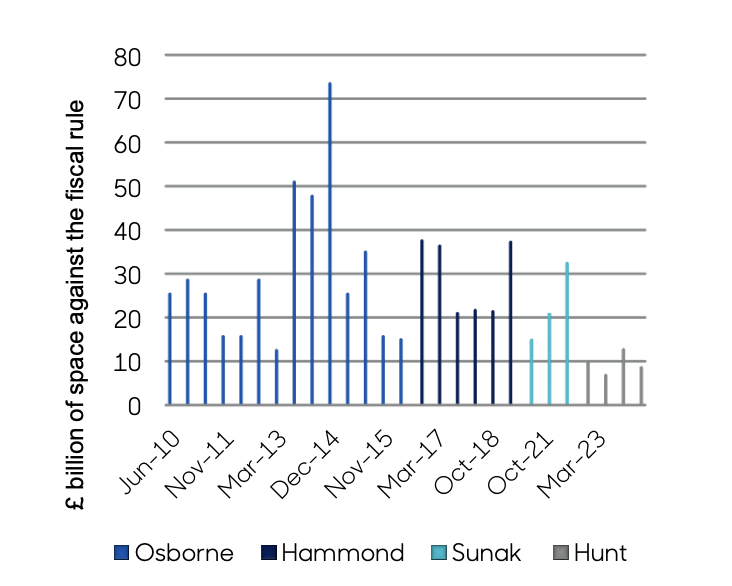

Indeed, Reeves is likely to want to build in some additional headroom against this target, which can then be used in the future. Frontloading economic “pain” at the start of a Parliament has been the standard practice of recent governments (see Figure 1). This would imply the need for an even greater degree of fiscal consolidation in the forthcoming Budget.

Figure 1: Previous chancellors have tried to create headroom against the fiscal rules

Source: abrdn, OBR, September 2024

Growth to the rescue?

In time, Labour hopes that its supply side policies will relax fiscal constraints by boosting potential growth. This agenda involves creating a more stable political environment, planning liberalisation to boost housing and infrastructure construction, industrial policy, and closer relations with the EU.

While there is certainly scope for better supply side policy along these dimensions to boost growth, they are likely to take time to have a material impact.

In fact, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) may downgrade its assessment of UK potential growth in the near term, as its current 1.5% estimate is quite optimistic.

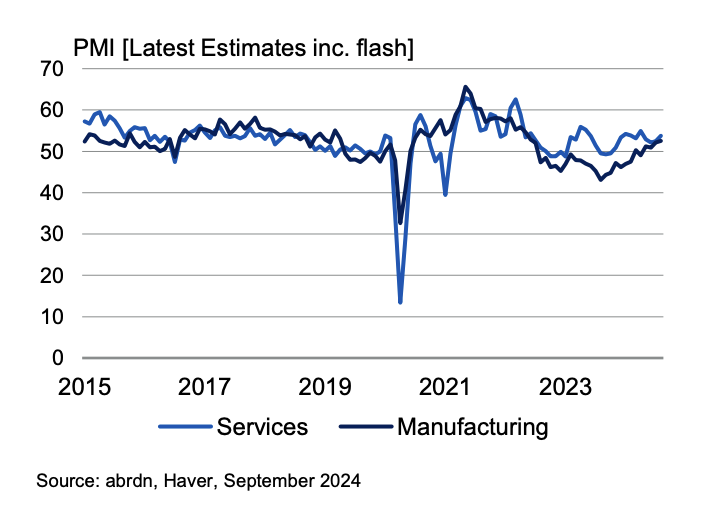

Meanwhile, the current cyclical strength of the UK economy (see Figure 2) has little impact on the medium-term fiscal outlook, which turns on potential growth.

It is even possible that the recent strength of the UK economy could mean the government’s funding costs will be higher than expected in the future, making the fiscal outlook even more challenging. To the extent that cyclical resilience is a sign that monetary policy is exerting less of a drag on the economy, this might imply that the UK’s equilibrium interest rate is higher. A higher equilibrium rate, all else equal, is likely to feed into higher gilt yields – i.e. a higher cost of debt for the government – over the longer term.

We are minded to somewhat downplay these arguments, and expect monetary policy to gradually ease over the next few years, with low global equilibrium rates combined with low domestic productivity growth in the UK, helping to keep equilibrium rates relatively low.

Figure 2: The UK economy is experiencing a cyclical upswing, although this doesn’t necessarily help Reeves

But, either way, economic growth will not solve Labour’s immediate fiscal challenge.

BoE losses could be the government's gain

Labour can create some fiscal space by changing the way monetary policy operations interact with the public finances. Currently, the large losses that the Bank of England (BoE) is making on the Asset Purchase Facility (APF), which could amount to £20 billion a year over the Parliament, count towards the fiscal rules.

The BoE is set to decide the pace of next year’s asset sales at its September policy meeting. It is possible the Bank decides to slow the pace of its sales, which would somewhat reduce the speed at which the losses in the APF are crystallised. However, the ongoing financing of the APF would continue to generate losses, because of the cost of the reserves issued to finance the asset purchases. So, slowing the pace of quantitative tightening does not make the fundamental problem of monetary losses go away.

While these losses represent a very real hit to the consolidated public sector’s long-run budget constraint, there are other ways they could be reflected in the public accounts and fiscal rules, which may lead to less distortionary swings in tax and spending.

For example, the APF could be transferred directly onto the BoE’s balance sheet, while the Bank is then allowed to keep any future seigniorage revenue to eventually offset the losses. Alternatively, the government could just tweak the fiscal rules to exclude the impact of monetary operations.

It is possible that Labour is perceived as fiddling the rules by excluding these losses, risking a loss of market confidence. That’s one reason why the new government has been keen to project fiscal rectitude and further beef up the role of the OBR.

For now, Labour seems to have received little pushback from market participants or the BoE itself, so some sort of change is likely in the budget. This will help close some of the fiscal gap in five years.

A variety of tax increases likely

However, technical tweaks cannot close all of the shortfall against the fiscal rules. The result is that the Budget will have to involve several tax increases (see Figure 3).

Labour has ruled out increasing the rate of income tax, national insurance, VAT and corporation tax, so it will instead increase a variety of smaller taxes and close reliefs. It has already committed to increasing VAT on school fees, reforming the non-dom tax system, changing carried interest and extending the windfall tax on oil and gas. Collectively the government estimates these changes will generate an additional £8.4 billion in revenue, though the eventual amount is likely to be lower.

Other measures could include increasing the rate on capital gains perhaps up to the top rate of income tax, tightening exemptions on inheritance tax, and reducing pension tax relief. Labour may also allow the fuel duty escalation to kickin after years of being suspended, although this creates no fiscal room relative to the OBR’s forecasts, which are already conditioned on this increase occurring.

There are legitimate questions about the distortionary impact of some of these increases and whether they push against other aspects of Labour’s agenda. For example, increasing capital gains tax could stunt capital formation, and increasing it to an equivalent rate to income tax may put it above its revenue maximising rate.

Meanwhile, changing pension tax relief could increase uncertainty over retirement planning and blunt the push towards a greater home bias in pension investments.

All told, higher-than-expected borrowing strains on public services and alleviating planned real terms cuts to departmental spending will require the government to raise significantly more revenue than it implied during the election campaign.

Figure 3: Additional revenue raising measures beyond those announced are likely, but their magnitude will depend on the OBR’s fiscal forecasts

Measure | Current situation | Possible changes |

| Capital gains tax | Capital gains are taxed at 10% for basic-rate taxpayers and 20% for higher-rate taxpayers. There are different rates for property sales. | Changes to reliefs are very likely. There has been speculation Labour may align capital gains tax rates with income tax rates to reduce the disparity between different forms of income. However, the Treasury is currently assessing what the maximum tax optimising rate would be, which could lie somewhere below full alignment. It may also dissuade investment in certain assets like |

| Inheritance tax | Inheritance tax is charged at 40% on estates above £325,000, with exemptions and allowances (e.g., the family home allowance). | Changes to rates and reliefs are very likely. Labour may seek to lower the threshold or increase the rate, especially targeting large estates. Higher inheritance tax may be presented as addressing wealth inequality but may prompt more estate planning or tax avoidance measures. It may also be unpopular with older voters and property owners. |

| Employer national insurance contribution | Employers currently pay NIC at a rate of 13.8% on employee earnings above £9,100 per year | Possible. During the campaign, Labour committed to not increasing National Insurance. But subsequently, that rhetoric has been softened to not increasing employee contributions, leaving opening the possibility of increasing the employer component. |

| Fuel duty | Fuel duty is 52.95p per litre for petrol and diesel. Stated policy is to reverse the latest 5p cut and do RPI uprating. The OBR conditions on this increase, which raises the tax take by £2.5 billion to £27.3 billion in 2025-26. In practice, fuel duty has been frozen since 2011. | Possible. Labour may break with previous precedent and allow fuel duty to increase in line with stated policy. However, this is likely to be politically painful given it high-profile and broad-based impact |

| Reducing pension relief for top-rate taxpayers | Pensions contributions are tax-deductible at the marginal rate of income tax (20%, 40%, or 45%). | Labour has not ruled out lowering pension tax relief for 40% and 45% taxpayers down to 20%. Changes in this area are unlikely to be a priority, especially as it clashes with other objectives such as increasing pension saving. But it is an option if the government needs to raise large amounts of revenue. |

| Increase in the bank surcharge | 8% on profits above £25 million, on top of the 25% corporation tax rate. | Unlikely. Labour could consider increasing the bank surcharge or closing loopholes. It may deal with political concerns about paying banks’ interest on reserves without interfering in monetary policy operations. But it may make the UK less attractive as a financial centre. |

Lizzy Galbraith is political economist at abrdn.

Luke Bartholomew is deputy chief economist at abrdn.

Paul Diggle is chief economist at abrdn at abrdn.

ii is an abrdn business.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.