Two decades after the tech bubble: Is it different this time?

We look at lessons learned from the 2000 tech crash and suggest four tech investments to buy and hold.

29th October 2019 12:03

by Jeff Salway from interactive investor

We look at the lessons learned from the 2000 tech crash, considers high-profile stocks such as Uber and WeWork, and suggests four tech investments to buy and hold.

With the backing of several Wall Street banks and some of the world's biggest fashion names, Boo.com caught the eye when it went live in November 1999. Its aim of becoming the first genuinely global online fashion retailer, providing services in different languages and currencies, made for a compelling proposition. Yet six months later it was over, as liquidators were called in and investors were left with burning holes in their pockets.

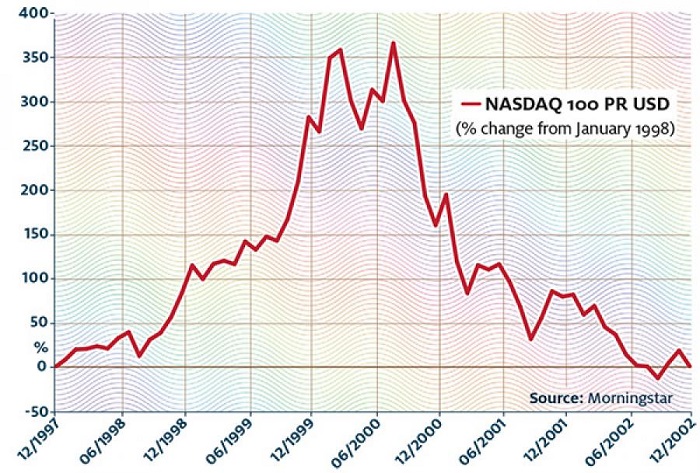

Boo.com lives on as perhaps the most famous symbol of the dotcom boom and bust story. It was a salutary lesson for investors, as was the wider impact of the dotcom crash. The tech-dominated Nasdaq index rose sharply to a peak of 5049 on 10 March 2000, before tumbling 76% to 1140 by 4 October 2002. Most listed dotcom companies had gone bust by the end of 2001, while even major technology brands such as Oracle and Cisco lost a large chunk of their value, leaving investors nursing painful losses.

Two decades on and tech-focused public offerings have been in the headlines again, with the amount raised in 2019 expected to beat the record set in 2000. But with a number of tech firms seemingly overvalued and several of those initial public offerings (IPOs) falling short of expectations, there are whispers of history repeating itself.

Snapchat owner Snap Inc (NYSE:SNAP) was valued at $24 billion (£19.6 billion) when it listed in 2017, but shares now trade well below the listing price and it posted heavy losses in early 2019. Ride-hailing service Uber (NYSE:UBER) went to market in May at a valuation of $82 billion, only to see its share price fall immediately on the opening of trading and remain well below that initial figure. Rival Lyft suffered a similar experience.

The example of Uber in particular is held up as echoing the stories of the dotcom boom.

"It shows no more sign of becoming profitable than it did before," says Simon Edelsten, manager of the Artemis Global Select fund and the Mid Wynd International Investment Trust (LSE:MWY). "It's relying on the kindness of strangers and its IPO takes me back to the worst of 2000."

Thomas Becket, chief investment officer at Psigma Investment Management, agrees, pointing to an admission in Uber's offering document that it "may not achieve profitability". "When companies can come to the market and tell people they might never make money, then questions have to be asked," says Becket.

"In the case of Uber, it should be obvious that there is a potential long-term growth story, but the numbers just don't back it up in terms of operating margins or the ability to make profits."

Further echoes of 1999 may be found in the example of WeWork, which in September aborted its planned stock market listing due to a lukewarm reception from investors. Like many dotcom start-ups, WeWork is not a technology company. However, its pricing and marketing creates a perception that it is, beguiling the market into giving it a higher valuation.

The same goes for certain other high-profile stocks, according to Becket. "WeWork and Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA) are not tech companies – they are property and automakers, respectively – but they are priced like tech companies," he explains.

"If you applied valuations to them as being in the property and automaker sectors, they would be much lower."

The same could apply to other big technology brands. Is Amazon, for example, a technology company, a cloud computing infrastructure provider or a retailer?

Rise and fall of the Nasdaq

-gained 358% Jan 1998 to March 2000

Learning from history

Similar questions arose as the dotcom era gathered momentum. The likes of Boo.com and Pets.com were retailers using the internet as a distribution channel, but they were considered to be tech stocks and their valuations reflected that. It was the same with Webvan, the grocery delivery service that saw its price tumble from $30 a share at IPO in November 1999 to just 6 cents a share when it ceased trading, 20 months later.

This is why focusing on fundamentals and the business model of a company can help investors avoid repeating the mistakes of the dotcom crash, when many were dazzled by the hype surrounding certain firms rather than focusing on their actual value, says Mark Leach, portfolio manager at wealth manager James Hambro & Partners.

"Always focus on value, cash and profits. It's a lesson that investors repeatedly fail to heed – that's why these bubbles happen."

Investors can avoid the value traps by seeking to establish what a company is really worth and steering clear if it’s too hard to value. Edelsten at Artemis has so far avoided the Chinese internet giants for that very reason. Similarly, the difficulty in predicting the impact on future valuations of a steep increase in regulatory oversight and costs keeps him away from Facebook (NASDAQ:FB) and Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL).

The problem, according to Becket, is that when investors find a story compelling, they tend to give a company extra leeway. But good stories don't always make good investments.

"People are always looking for the new next big thing, and have done all through history. They want to back the winners of tomorrow and will often give a lot of latitude to those they like the look of."

While huge amounts of (largely venture) capital have been invested in WeWork, Uber, Lyft (NASDAQ:LYFT) and other tech-like organisations, those companies aren't making profits. Indeed, as Leach notes, 84% of US companies pursuing IPOs have no profits to report.

"If the 17th-century Dutch bubble was a mania for tulip bulbs, today's Silicon Valley bubble is an obsession with unicorns – tech companies that can hit $1 billion valuations,” Becket says. “The irony is that the inspiration for this is the success of companies like Amazon and Google – the phoenixes that rose from the ashes of the last tech crash."

Don't look back in anger

That crash left a trail of broken dreams and investors with burnt fingers. But that's just one side of the story, as the lessons of the survivors may equally be worth heeding. After all, the notable successes from the era include the likes of Google and Amazon.

"Not every tech stock that came to market was rubbish," Edelsten points out. "Those that survived had a 'network effect' – the quality of products got better as the companies grew, which is unusual for big companies."

It's worth remembering too that the dotcom boom also saw a surge of investor funds into media and telecoms firms as well as tech start-ups. The technology, media and telecoms (TMT) sector accounted for more than 40% of global merger activity in 2000, at a total value of more than $1.5 trillion.

Looking back now, however, Edelsten notes that it was largely the internet stocks that made it through the crash. "In the media sector, the broadcasters were eaten up and print lost its advertising revenue to the internet. In 2000 you might have thought these companies were all on the same side, but each of the TMT sectors has a different story."

Tech performance turns few heads over 20 years

| Fund sector | Cumulative total return (%) | Annualised total return (%) | Value of £100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biotechnology | 430 | 8.7 | 530 |

| Con Goods & Services | 192 | 5.5 | 292 |

| Communications | 96 | 3.4 | 196 |

| Ecology | 137 | 4.4 | 237 |

| Energy | 151 | 4.7 | 251 |

| Financial Services | 187 | 5.4 | 287 |

| Healthcare | 559 | 9.9 | 659 |

| Natural Resources | 441 | 8.8 | 541 |

| Precious Metals | 531 | 9.6 | 631 |

| Technology | 190 | 5.5 | 290 |

Note: Table shows total returns from 10 different Morningstar UK fund sectors over 20 years to 31 August 2019. Source: Morningstar Direct

Fangs for the memory

The companies that survived were those with the financial resilience to cope when the funding dried up. They included the likes of Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), Google and eBay (NASDAQ:EBAY), who took greater market share as their competitors fell by the wayside. "We kept an eye on Google and Amazon and could see that the underlying cash flows were still improving and that revenue growth was fantastic. That wasn’t true of the rest of the TMT bubble," Edelsten explains.

The resurgence of the technology sector in recent years suggests that a certain amount of what people hoped or expected to happen when they invested in dotcom stocks has actually happened. To some extent it's just taken longer than they thought, with the advance of technology belatedly allowing services to deliver on their promises.

While the problems experienced by the likes of Uber and WeWork may take some investors back to 1999, the companies in the vanguard of global technology tell a different story.

Five tech giants – Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Google (in the form of owner Alphabet), Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT) – are all among the top 10 stocks in the US's S&P 500 index. The so-called FAANG stocks Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX) and Google are a feature of many global growth funds and trusts, alongside the likes of Tesla, Oracle (NYSE:ORCL), Microsoft and, increasingly, Chinese giants Tencent (SEHK:700), Baidu (NASDAQ:BIDU) and Alibaba (NYSE:BABA).

Two decades ago the internet was groundbreaking and the potential seemingly endless. Yet smartphones were still several years away and broadband was in its infancy. Now, tech business models are based on proven technology infrastructure, says Leach. "Many of the most powerful businesses of recent times have used the proliferation of the internet to build global networks that have created exceptionally profitable and cash-generative businesses. The success of these companies has allowed them to out-invest or buy any new competition that has emerged."

Making the right calls

There may be a few parallels between the current market and the dotcom hype of the late 1990s, not least in the form of valuations that can seem difficult to justify. But the lessons to heed when investing in technology stocks and funds are relevant across all sectors – don't believe the hype, do your own research, diversify and remember that a good story doesn’t always make for a good investment.

"It's quite right to get excited about the products that are going to sell well, but it doesn't mean you then go off and buy the shares," says Edelsten.

"Look at the financials and try to work out the relationship between what you're paying and things like earnings, cash flow and margins. Unless you do that, you could find yourself invested in a company that looks very successful but unable to work out why the share price is going down."

Four tech investments to buy and hold

Loomis Sayles Growth Fund Technology is the biggest sector exposure in manager Aziz Hamzaogullari's portfolio, with an emphasis on patient investing and holding on to the stocks it favours. Amazon, for instance, has been in the portfolio since 2006, with Facebook and Alphabet (owner of Google) also long-term holdings.

Polar Capital Technology Trust (LSE:PCT) US tech stocks account for around 70% of the holdings in the portfolio. Manager Ben Rogoff looks for the next big tech winners, but the top 10 holdings list currently reads like a rundown of global tech giants, including Apple, Amazon, Tencent, Microsoft, Alphabet and Facebook.

Allianz Technology Trust (LSE:ATT) run since 2007 by Walter Price, a tech investor since the mid-1970s. The trust doesn't rely on the big beasts: while Facebook and Microsoft are the biggest holdings (and the US accounts for almost 90% of the portfolio), the top 10 also features less well-known names such as Zscaler (NASDAQ:ZS), Octa, Micron (NASDAQ:MU) and Akamai (NASDAQ:AKAM).

Scottish Mortgage (LSE:SMT) This global vehicle has a big focus on tech. Manager James Anderson looks for companies whose technological innovation keeps them ahead of their peers, and remains invested in them over the long term. Amazon and Netflix are in the top 10, alongside Chinese businesses including Alibaba and Tencent.

Heroes and zeros of the dotcom bust

In February 2000, the Jupiter Global Technology fund was launched. Weeks later the dotcom crash began and the fund saw its price fall 32% in just two months. It was far from the only fund to fall victim when the dotcom boom came to an abrupt end, with Gartmore UK Techtornado, Investec Wired and Framlington NetNet among the others to pay the price for launching too close to the peak of the market. Some fund managers did get it right, though. Bill Mott of Credit Suisse sold out of most of his TMT holdings before the market peaked in March 2000, investing instead in 'old economy' companies that had fallen out of favour.

As manager of the Invesco Perpetual Income funds, Neil Woodford made his name by avoiding sectors or companies that were in fashion and considered overvalued. While he suffered during the dotcom boom, he was rewarded for his patience when his funds avoided the worst of the crash that followed.

Then there was Tony Dye, of Phillips & Drew. He avoided tech stocks entirely and kept a large chunk of investors' money in cash. They left in droves and performance suffered, but Dye was vindicated when the company swerved the dotcom crash. Unfortunately for Dye, his employers had lost patience at the peak of the market and he was sacked before events proved that he had called it right.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.