Forget about raw returns: here’s why risk-adjusted returns matter more

Risk-adjusted returns matter most because you can scale an asset's position to match your desired risk level, maximizing your potential returns in the process.

13th December 2024 09:12

by Stéphane Renevier from Finimize

You can boost an asset's risk and return contribution to your portfolio by increasing your allocation. Since position sizing lets you target a specific risk level, focusing on risk-adjusted returns is key – it helps you maximize the returns achievable for that level of risk.

- Using sensible leverage on low-risk, high-risk-adjusted return strategies – for example, risk-parity portfolios – can amplify your returns without excessive risk. This approach can turn “boring” assets like bonds into top-performing investments.

- The implications are big: high-risk, high-reward investments may not be the best way to get the high returns you’re after. Handled strategically, those “boring”, but highly efficient assets could surprise you.

For most investors, risk is almost an afterthought – all the spotlight is on potential returns. That’s why speculative plays are so tempting: nail it, and the upside feels unbeatable. But here’s the thing: you don’t need high-risk bets to aim for high returns. With the right strategy, even “boring” assets can become return-generating powerhouses. Let’s break down why focusing on raw returns might be a mistake, and how to turn any investment into a rocketship.

Risk, or return?

Which of those two would you pick:

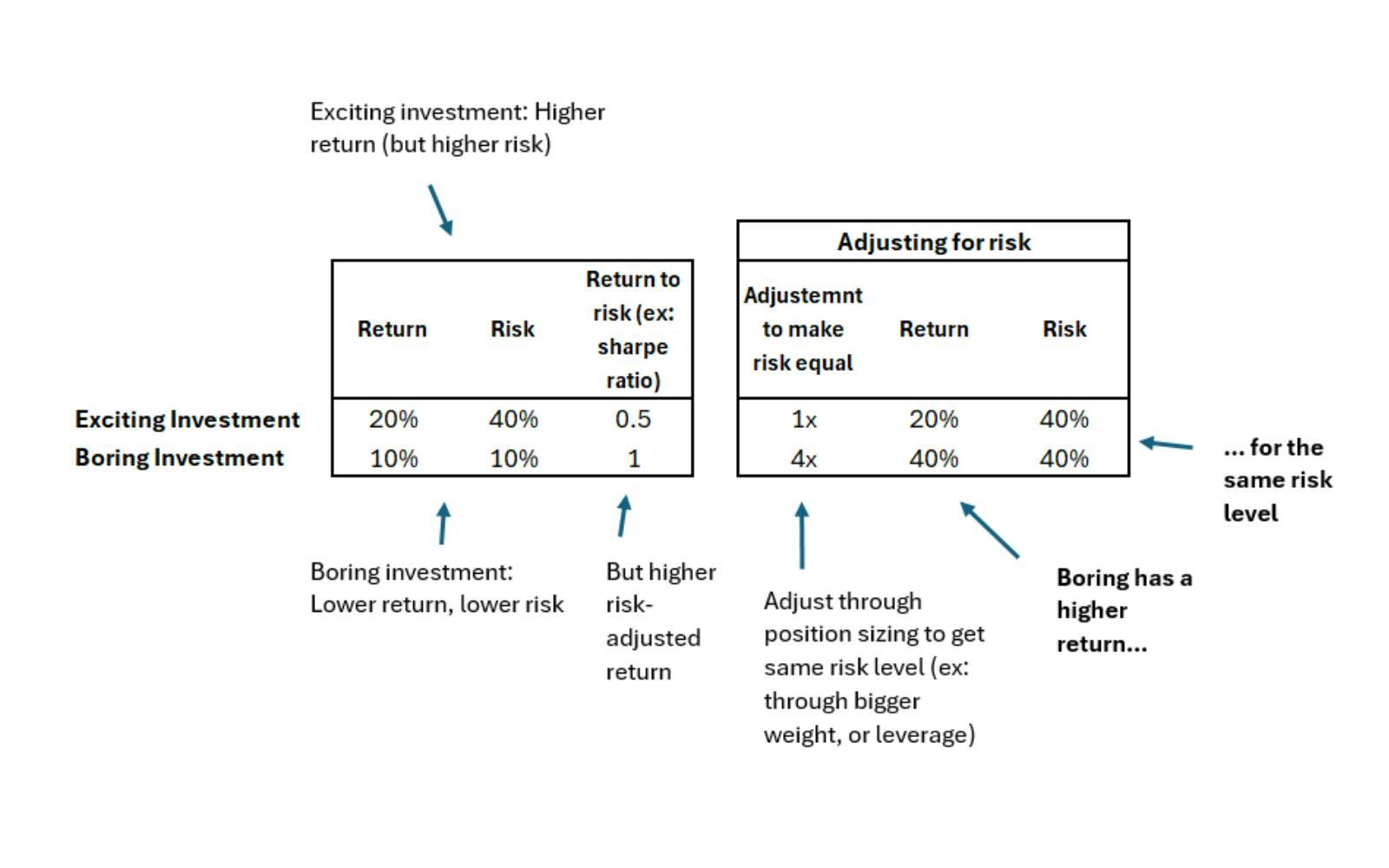

- An “exciting” investment with an expected return of 20% but a risk of 40% (whether that’s volatility, maximum loss, or something else)

- A “boring” investment with 10% expected return and 10% risk

Most investors would snap up the 20% return without a second thought. I mean, if you can stomach the 40% risk, why not grab the biggest upside? But here’s the problem: that mindset overlooks a game-changing lever: position sizing.

See, the impact an asset or strategy has on your portfolio isn’t just about its return: it’s also about how much you allocate to it. An asset’s contribution is simply its return multiplied by its weight. By tweaking that weight, you can effectively dial up or dial down its return impact on your portfolio.

For example, doubling your allocation to a 10% return asset has the same impact as doubling its expected return. And if you’re using leverage (which means you’re not limited to a 100% allocation), this means you can pretty much target any return you’d like, whether it’s from a high-octane investment or a boring one.

Back to the example: here’s how boring could actually beat exciting. The boring asset is four times less risky than the exciting one, so you could allocate four times as much to it and it still wouldn’t be any riskier than the exciting option. And here’s where it gets interesting: with four times the allocation, it’s got the same risk, but its return jumps to 40% (that’s 4x 10%) – double the exciting option’s 20%. By picking the highest risk-adjusted asset and tailoring your position size to your risk tolerance, you’ve squeezed out the maximum possible return for that level of risk – turning a “boring” investment into a top performer. Not so boring now, is it?

Risk-adjusted returns matter most because you can scale an asset's position to match your desired risk level, maximizing your potential returns in the process. Source: Finimize.

Why should you care?

The key lesson here so far is that an asset or strategy’s raw return isn’t what matters most as it can be dialed up or down based on how much you allocate to it. The same goes for risk. What really matters is risk-adjusted return because that’s how you wring out the most return, with only the risk you’re willing to take.

Of course, in practice, things aren’t that simple. Estimating an asset’s true risk is tricky, and even the investment industry’s most commonly used risk-adjusted metrics – like the Sharpe or Calmar ratios – are just starting points. Plus, allocating more to lower-risk assets means tying up more of your money. But in most cases, pairing Sharpe ratios with a little common sense can get you pretty far. And for the money issue, responsible use of leverage can be a game-changer.

Take a risk-parity portfolio, for instance. A classic, unlevered version might hold 15% in stocks, 40% in bonds, 20% in gold, and 25% in other commodities. For the reasons explained earlier, the higher weight in bonds reflects their lower risk. By allocating more to them, you can balance out their impact on the portfolio with stocks, creating a more even and stable mix.

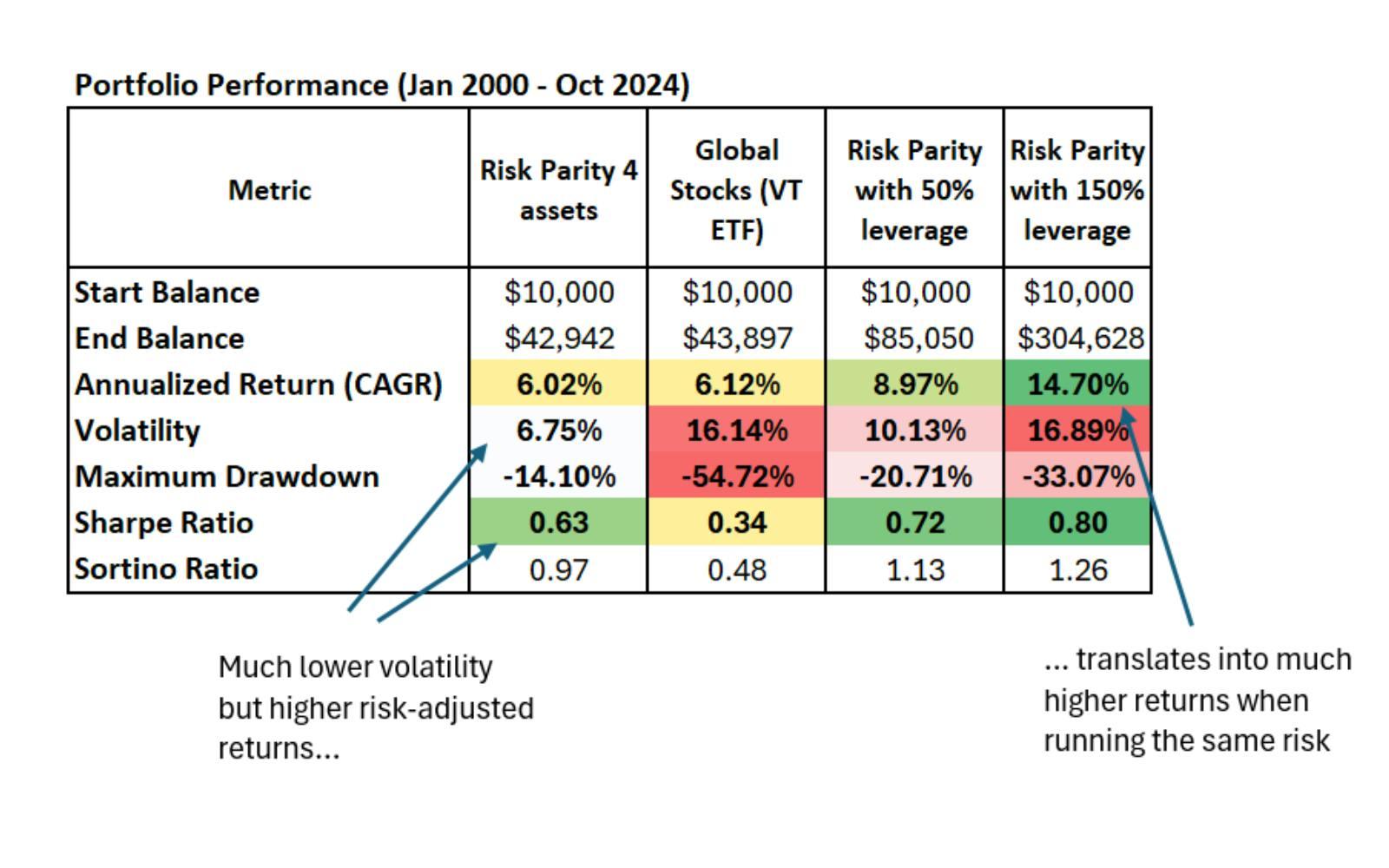

Now, I backtested a simple four-asset risk parity portfolio (with weights calculated dynamically), and here’s what I found: it delivered 6.3% annual returns since 2000, on par with global stocks. But here’s the thing: it did so with only a third of the volatility and a maximum loss of just 15%, compared to 55% for global stocks. Its Sharpe ratio was 0.63, double that of global stocks at 0.34, meaning you can expect twice the return for the same unit of risk. And sure, Sharpe ratios aren’t everything, but it’s hard to argue that risk-parity doesn’t beat global stocks in risk-adjusted terms. And however you define risk, it’s much less risky.

Still, 6.3% might feel underwhelming if you’re aiming for higher returns. Some might think sticking with stocks is better – even though they haven’t delivered better returns over the same period and come with bigger losses and more wild swings. Point is, risk-parity is a lot like the second asset in our earlier example: it offers solid risk-adjusted returns, even if the raw returns don’t seem very exciting at first glance.

What’s the opportunity then?

So here’s what you could do. If you’re comfortable taking on more risk, you could use a reasonable amount of leverage to boost both the risk and return of the steady risk-parity portfolio. For instance, adding 50% leverage would have increased returns to 9% per year while keeping volatility at 10% and your maximum loss at 20%. That’s still less risky than stocks, but it now generates bigger returns (in fact, even higher than the top-performing index – the S&P 500 – over the same period). That’s what allocating to a higher risk-adjusted return strategy can do: for the same level of risk (or, in this case, even less), you can get higher returns.

Now, I can practically see the fear in your eyes at mere mention of the word “leverage”. And look, I won’t sugarcoat it: leverage is risky. It amplifies both your gains and losses, which means if markets swing more than you expect, you could face margin calls (that’s your broker demanding that you put up more money to cover your bets) or significant losses. That’s why it’s crucial to use leverage responsibly: focus on strategies or assets you’re confident are less risky, keep its maximum level reasonable, and always have a plan for handling worst-case scenarios (yes, even worse than anything we’ve seen before). If that’s how you use it, then adding leverage to a less-risky strategy like unlevered risk-parity isn’t any riskier than adopting a riskier strategy like an all-stock portfolio.

Of course, you could crank up the leverage further to match the risk level of stocks and aim for even higher returns. With 150% leverage, you’d get the same volatility as stocks – but you’d get 15% return per year (assuming there’s no cost of using leverage, which isn’t quite true in practice). Yep, for the same volatility, you’d now gettwicethe return on stocks. And that’s no coincidence: the risk-parity portfolio’s Sharpe ratio is twice that of stocks, meaning for the same level of risk, you’d be getting twice the bang for your buck.

Lower volatility but higher risk-adjusted returns strategy translates into much higher returns when running the same risk level. Source: Finimize.

That said, cranking up leverage to match stocks’ high volatility is purely for illustration – this is not a recommendation. As I mentioned earlier, it’s wise to stick to a reasonable amount of leverage – and for most people, that’s around 50% in this case. And that’s great: by applying sensible leverage to a portfolio with better risk-adjusted returns, you can achieve higher returns for the level of risk you’re comfortable taking. This isn’t just a tweak – it’s a serious alternative to going all-in on stocks.

What’s more, this tactic can be useful for your whole portfolio or for individual assets. Take bonds: many retail investors write them off because of their low returns. But hedge funds know better. By using leveraged instruments like bond futures, they turn these “boring” assets into high-octane performers, often racking up double-digit – or even triple-digit – returns.

Remember: the point isn’t to go all-in on leverage as you chase some sky-high return. Leverage can be costly and risky, and it requires caution and a proper risk management process – even for a seasoned pro.

Rather, the point is to reconsider how you view investments. Don’t dismiss high risk-adjusted return assets just because their headline returns seem modest. By sizing your positions to dial up the returns on an asset or strategy, you can shift your focus to finding the highest risk-adjusted opportunities. That opens up a world of possibilities – no asset is off the table. And it means you can body-swerve the market’s dangerous obsession with high-risk, high-return plays. You don’t have to rely on them to chase big returns. By focusing on risk-adjusted strategies instead, you can aim for those high returns – but in a smarter, more strategic way.

Stéphane Renevier is a global markets analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.