Big final salary pension schemes dump UK shares

30th May 2023 13:28

by Alice Guy from interactive investor

Equities ruled the world of final salary pensions for decades, but a dramatic shift has occurred that leaves shares in UK companies out in the cold. Is the balance of power about to change again?

In the 1980s and 90s, big corporate pension schemes were massively underfunded. At the end of September 2016, the combined deficit for bigger final salary schemes was £419.7 billion, more than half the cost of total government spending for that year.

It was arguably more luck than judgement that schemes weren’t even worse off. A dramatic stock market bull run, aided by the 80s Big Bang, fuelled a near-700% surge in the FTSE 100 between 1984 and 1999. If stock markets had underperformed, deficits could have been catastrophic.

- Invest with ii: Open a SIPP | What is a SIPP | SIPP Cashback Offers

Today, the big pension funds are properly funded and back in the black, with the surplus in March 2023 a healthy £359.3 billion. And UK final salary (defined benefit, or DB) pension schemes are still a big player in the UK economy, with assets worth £1.28 trillion in September 2022, according to figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). That compares with £545 billion for defined contribution schemes and Pensions Policy Institute future book.

But there’s been a dramatic shift in the exposure of final salary schemes. Where once UK equities were king of the castle, it is bonds and international shares that now dominate.

With Jeremy Hunt reportedly encouraging pensions to invest in UK plc, we revisit history to understand how we got here and what the implications of backing the chancellor might be.

The ‘cult of equity’ to the ‘cult of bonds’

Until the 1990s, pension schemes were flying by the seat of their pants, with huge exposure to equities, relying on stellar stock market performance to balance out under-investment. There was a “permissive approach to corporate governance” and the “cult of equity” held sway. By the 1990s, the average UK final salary pension had 81% of its money invested in equities, and 57% on average in the UK stock market: an aggressive strategy even for an individual investor. In 1992, pension schemes owned a massive 32% of all quoted UK shares. Now, overseas investors own most UK quoted shares (figure 3).

In the 1990s, employers quickly began to wind up their lucrative pension schemes as poor management decisions came home to roost, and the true cost of DB pensions became clear. And as the pension schemes closed their doors, they also began reducing risk, increasingly moving from UK equities to bonds and overseas shares. There was an increasing focus on corporate governance, and pension funds quickly moved to “de-risk” and protect their existing increasingly older members with fixed and inflation-linked payments.

In 2009, Citigroup's global equity strategist Robert Buckland commented on poor equity performance, saying “the cult of the equity is dead. Long live the cult of the bond.”

- Benstead on Bonds: are bonds now the only game in town for income?

- How your portfolio will be impacted if higher interest rates endure

Instead of investing in the UK, pension schemes sold domestic stocks and spread their remaining equity exposure around the world. Just like a private investor who chooses a global fund, the big schemes sensibly diversified their geographical investment risk.

In 1993, the final salary schemes invested 57% in UK equities. That allocation dropped to 48% by 2000, 31% by 2010, 16% by 2015 and a paltry 6% by 2022. In contrast, investments in overseas equities remained relatively static, peaking at 30% in 2006 before gradually reducing to 19% in 2022.

But bonds have been the big winners. From 51% in the early 1960s, their exposure declined over the next 30 years to just 10%. However, they have become increasingly popular since hitting that low point in 1993, rising steadily to a record 58.5% in 2022.

Don’t blame pensions for falling UK asset prices

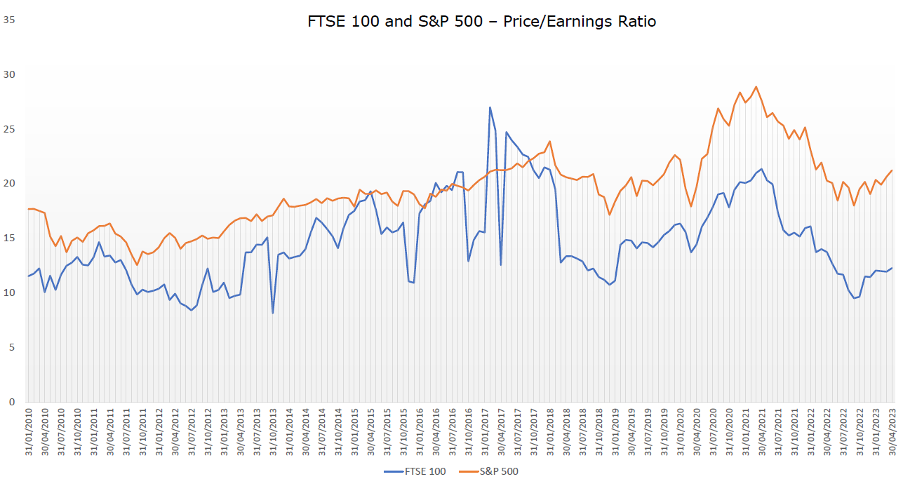

Some blame big pension funds for low valuations applied to UK stock compared to US peers. The price/earnings (PE) ratio (a measure of the relationship between price and earnings) of the FTSE All-Share was 12.3 at the end of April 2023 compared to 21.2 for the S&P 500.

But two trends happening at the same time doesn’t prove one caused the other. This chart shows that the fall in UK stock values compared to the US occurred mostly since 2016, after most of the pension scheme sell-off had already taken place. In fact, UK and US PE ratios were very similar throughout 2015 and 2016.

Source: Morningstar. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Rather than pension schemes being to blame for lagging UK share prices, Sam Benstead, deputy collectives editor at interactive investor, believes the change in fortunes is mainly due to market differences: “America’s thriving technology sector has driven its strong returns relative to UK shares. Meanwhile, British shares tend to be more mature business, returning plenty of cash to investors via dividends (the FTSE 100 index yields around 3.5% while the S&P 500 index pays out 1.5% in dividends), but lacking the big disruptor stocks from across the Atlantic.”

Hunt’s plan to force more risky UK pension investment

So, what is the future for the UK pension system? It seems the honey pot of defined contribution pension assets - expected to rise from around £545 billion today to £1.3 trillion by the 2040s - is proving too tempting for the Treasury.

Hunt recently hinted that he could force pension funds of all types to invest in UK private equity. Likewise, shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves has backed a proposed £50 billion ‘future growth fund’ and hinted at forcing pension funds to invest in fast-growing, highly risky UK companies, saying “Nothing is off the table.”

- Jeremy Hunt and his plans for your pension

- Work till you drop: government minister issues state pension warning

But, if the defined benefit pension debacle teaches us anything, it’s that we need to manage other people’s money carefully and match our risk to our investing needs. Jeremy Hunt’s plans to force more investment into private equity are extremely risky as small companies can and do fail, especially in the early stages. That’s why experienced investors often choose to invest through an investment trust, rather than an opened-ended fund. Investment trusts are closed ended, meaning that investors can often buy the trust at a discount to the value of assets – the net asset value, or NAV - held within the trust.

Dabbling in the world of private equity is not for the faint-hearted and is normally suitable only for informed investors with a high-risk appetite.

Like their DB cousins, defined contribution, or DC, pensions are currently well managed and have a duty to their members. Schemes are already investing 70% in equities for members 20 years from retirement, and de-risking as members get older, according to the Pensions Policy Institute’s DC Asset Allocation Survey.

Private pension savers also already invest more heavily in the UK than DB pension schemes. The extremely popular Vanguard LifeStrategy funds have a home bias, for example. The brochure states, “the home bias within the LifeStrategy fund range and the classic model portfolio range includes a 25% weighting to UK equities and a 35% weighting to UK bonds. The inclusion of a home bias within the fund range and the classic model portfolio range stems from a historic preference for domestic investments among UK investors.”

- Day in the life of a fund manager: Vanguard’s Mohneet Dhir

- Vanguard LifeStrategy funds: everything you need to know

- Vanguard LifeStrategy: the outlook for the next decade

Likewise, several of the top 10 most-popular funds and trusts bought by interactive investor customers are UK focused, including Fidelity Index UK, City of London (LSE:CTY) and Merchants Trust (LSE:MRCH).

We’ve reached a time when both DC and DB pension schemes are thankfully well managed, black holes are plugged and individual savers already invest heavily in the UK. Hunt should think carefully before he launches a potential firecracker into the system.

Graph shows the proportion of UK quoted shares owned by overseas investors. Data from the ONS.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.