Richard Beddard: high score surprises the scorer

A clean set of accounts impresses our companies analyst who rates this share 8 out of 10.

16th October 2020 15:15

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

A clean set of accounts impresses our companies analyst who rates this share 8 out of 10.

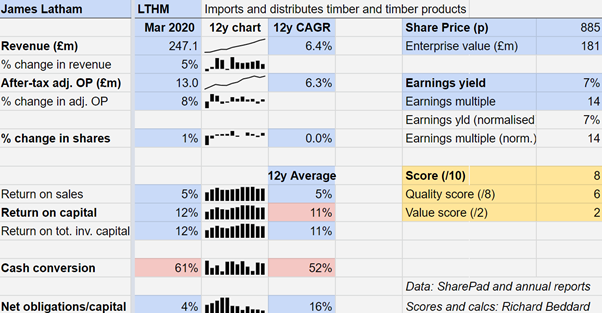

James Latham (LSE:LTHM) is something of a stalwart. An importer and distributor of timber it has grown both revenue and profit at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of more than 6% over the last 12 years.

That is not an exciting rate of growth, but it compounds. In Lathams’ last financial year ending in March 2020, revenue and profit were more than double the level they were in the year to March 2008 - before the construction industry went into recession during the financial crisis.

Although James Latham earned less profit in 2009 and 2010 than it did in 2008, post-tax Return on Capital (ROC) bottomed out at a reasonably healthy 7%.

As solid as oak

Fast forward to the current pandemic and Latham is showing signs of resilience once again. At its Annual General Meeting (AGM) in September, the company revealed that revenue in the first five months of the year to March 2021, from April to August, was 20% lower than in the same period last year and the company had been profitable.

In the early days of the pandemic, reduced operations served the NHS and other customers, but revenue fell to 40% of the prior year. Since then builders and joiners have been busy and trading has recovered, although as the second wave of coronavirus intensifies we cannot know that will continue.

Lathams owns brands, has centuries of experience in sourcing timber, and was early to recognise the importance of sustainable wood products, but it essentially supplies commodities and products for which there are plenty of alternatives: softwood, hardwood, plywood, engineered wood, door blanks, cladding, decking and even acrylic paving.

Through its “How well do you know us” campaign, James Latham is introducing customers to its widening product range. Source: James Latham

Though Lathams is stocking more higher-margin ‘specialist’ products, they are not that special, so what else is driving growth?

Cash conundrum

My investigation starts with perhaps the weakest looking of James Latham’s financial ratios: Average cash conversion:

Investors are generally reassured when cash flows are high in relation to profit, preferably equalling or even exceeding it. But 2020 was a good year for James Latham, when it earned just over 60% of profit in cash. Its 12-year average is only 52%.

This could be a sign that the profit being reported is not real, that it has been inflated somehow by creative accounting.

I doubt that. Lathams’ accounts are among the cleanest I have come across.

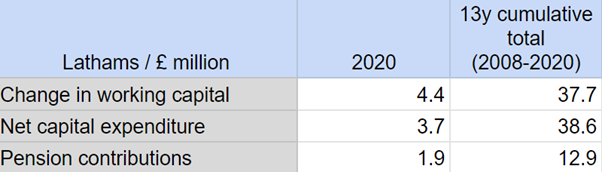

This table shows where the cash has gone:

Main uses of cash. Net capital expenditure is purchases of property, plant and equipment less sales of property, plant and equipment. Pension contributions are payments to the pension scheme in excess of the charge to profit. Sources: SharePad, and annual reports.

At the bottom of the list is pension contributions in excess of the amount charged to profit. Pension accounting is very complicated and, to be honest, I do not know whether profit or cashflow gives the truer picture. Relative to net capital expenditure and changes in working capital, at £12.9 million, pension contributions have been a modest drain on cash over the years.

Over the long term, net capital expenditure has gobbled up most cash, a total of £38.6 million, although in 2020 capital expenditure little more than depreciation, which is charged to profit. Capital expenditure varies a lot because once in a while, for example in 2017 and 2018, Lathams splurges on new facilities, buying land, buildings and equipment, and relocating so that it can sell more.

The company experiences the cash impact of investment as soon as it spends the money, but profit is only reduced by a fraction of the investment each year as the cost is spread out or depreciated. When the company buys land, the cost is not deducted from profit at all.

Working capital has used up a cumulative £37.7 million in cash since 2008. Lathams holds a lot of stock and each year that it plans to grow it must buy more. It also gives customers more than 50 days to pay on average, which is credit it must finance.

This would be a concern if the company were extending more credit to customers or building up ever bigger stocks in relation to the revenue it earns, but working capital has grown at the same rate as the business. For reasons I will come to in a moment, the company wants to maintain high levels of stock and receivables, even though it is costly.

If Lathams was happy not to grow, its thirst for capital would be slaked. It would only need to spend enough to replace the stock it had sold in the year and maintain its warehouses and showrooms.

Growth though, is capital intensive, which is why cash flow lags profit.

Capital intensity as competitive advantage

Having read some of its annual reports I am sure James Latham does many things well, but I think one of its biggest strengths stems from its apparent weakness: cash conversion.

James Latham wants to be the “supplier of choice” in the UK and Ireland to joiners, door and kitchen manufacturers, shopfitters and other market sectors.

Timber largely comes from abroad, and to be sure you can supply it when and where customers want it, you have to maintain large stocks and a nationwide network of distribution centres.

Combine its financial commitment to buy and store all this wood with the company’s vast experience (it is 282 years old), and motivated staff, and you end up with a good reputation. That reputation should be burnished during the stop-go conditions induced by the pandemic. Customers will value suppliers that deliver in the most trying circumstances.

A thirst for capital, and the company’s prudent financial policies, mean it is unlikely to grow rapidly, but perhaps it will continue to grow dependably.

Strategies like this are not fashionable among investors, who generally prefer “asset light” businesses, but it has been good for Latham’s shareholders.

Lathams reminds me of kitchen supplier Howden Joinery (LSE:HWDN), which may well be a customer. It maintains near 100% stock availability and gives builders enough credit to complete a job before they pay the company.

It also reminds me of ingredients company Treatt (LSE:TET), which stockpiles citrus oil when prices are low to ensure it can supply customers at reasonable prices when demand is high.

James Latham prospered through the minor recession in construction and housebuilding after the financial crisis, but we have not had a really big crash in the housing market since the 1990’s.

What effect an event like that would have on Lathams, I cannot say. But the company is debt free and thinks it is strong enough to survive any downturn. I agree.

Scoring James Latham

Does the business make good money? [1]

? ROC is adequate but not exceptional

? Profit margins are modest but may be improving

+ Cash flow is weak

What could stop it growing profitably? [1]

+ Competition unlikely to be as committed

? Major recession, especially in housebuilding

? Non-payment of receivables

How does its strategy address the risks? [2]

+ Investment in stock and facilities maintains reputation

+ Widening product range exploits it

+ Prudent finances

Will we all benefit? [2]

+ Latham family are owner-managers

+ Directors not overpaid

+ Looks after staff

Are the shares cheap [2]

+ A share price of 885p values the enterprise at £181 million, or about 14 times adjusted profit

This was a difficult article to write because it felt like I was spreading a heresy: that weak cash flow can be a good thing. That conflict did not leave me when it came to scoring the share.

As one of the least profitable and cash generative firms I follow, I am surprised James Latham achieved 8 out of 10 even though I am the scorer!

Nevertheless, it is probably a good long-term investment.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

Richard Beddard is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.