Olympics special: why Japan’s Nikkei feels a bit like 1989

28th July 2021 08:52

by Julian Hofmann from interactive investor

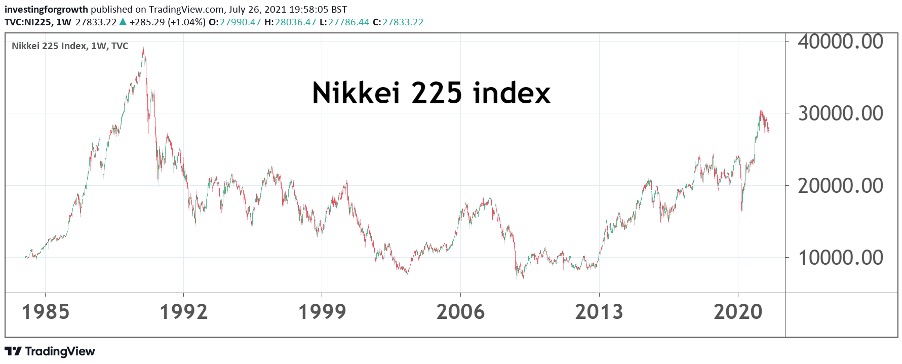

With Japan’s Nikkei passing the 30,000 mark for the first time in 30 years, it is worth remembering the strangeness of that era when you buy Japanese equities in this Olympic year.

Investors with long memories will recall watching Saturday Night Clive on ITV in the 1990s. Aussie writer and broadcaster Clive James would always be very amused by a Japanese game show called Endurance, where competitors had to undertake a series of painful, masochistic tasks (being covered in fish food and nibbled by catfish, for instance) in the name of winning a prize. That impression of whacky strangeness is something that lingers on when investors contemplate buying Japanese equities.

The sheer excess and craziness of the Nikkei peaking at over 38,000 in 1989, before crashing spectacularly, always seems to leave an indelible mark. However, with many of the competing indices trading on huge price-to-earnings multiples, the relative bargain status of Japanese shares is worth a sober assessment when it comes to diversifying a portfolio. Surprisingly, the truth about Japanese equities is much more conventional than their game shows ever will be.

- Japan: trusts have edge over funds in medium to long term, research finds

- Subscribe to the ii YouTube channel for our latest interviews and video content

Anatomy of a bubble

Japan went on a 40-year bull run between 1950 and 1990. At the height of the boom in 1989, the price-to-earnings ratio for the Japanese market was an astonishing 70 times, while the subsequent crash destroyed a mind-boggling $2 trillion in shareholder value. In fact, that number doesn’t capture the scale of the disaster. Many assets, including equities and property, lost 99% of their value from the very height of the boom.

There was also the sense that whoever benefited from the Nikkei’s rise, it certainly wasn’t the average Japanese investor – between 1982 and 1992, which encompassed the peak boom era, retail investors in Japanese mutual funds saw an average rate of return of only 1.74%, compared with a market return of over 9%. So, who made the profits?

At first glance this seems completely counter-intuitive, but it is only when you dig into the history of the bubble that you understand how utterly, shamelessly, corrupt the entire system was. In fact, this was as much a symptom of Japan transforming itself from a high-growth economy to one where earnings were slow and mature, as of natural excess, but the level of graft is jaw-dropping, nonetheless.

- Find a great way to invest in Japan with these ii Super 60 recommended funds

- Buy low, sell high: should investors follow Warren Buffett into Japan?

The main problem was not so much that investors were deluged with suspect IPOs – getting a stock market listing in Japan was always notoriously difficult – it was that botched regulation created perverse incentives for a whole host of dodgy practices. For example, in 1989 it was estimated that 67% of companies on the Nikkei had crossholdings in other firms, often in supposed competitors, which led to cosy management deals and created little incentive to reward shareholders – dividends were always historically low in Japan. There simply was no discernible corporate governance.

The Big Bang

The list of shame is embarrassingly long: small retail investors saw their ring-fenced funds used to illegally compensate the losses of larger clients; the government set up secret investment vehicles to invest in the shares of politically connected companies, often with ties to the Yakuza (Japan’s equivalent of the Mafia); banks lent indiscriminately to property developers to shore up their own asset prices– the list goes on and on...

So, has anything in the intervening 30 years changed? The short answer is yes. A host of accounting scandals - Olympus, Toshiba – came to light largely because of a “Big Bang” in 1996 that completely overhauled corporate governance standards and ended the perverse incentives that the previous regulatory regime had created, particularly the maintenance of asset prices as the only goal.

Overall, it is fair to say that the drive for reform means that the Nikkei has conclusively lost its “Wild East” reputation – that dubious honour now belongs to Shanghai. The proof of this is that foreign investors now account for up to two-thirds of the trading volumes on the Nikkei and TOPIX exchanges. Not all of this is down to the strange disappearance of the Japanese investor - a phenomenon linked to the defensive saving habits that Japanese consumers took on in the aftermath of the bust – but disclosure, accounting and accountability reforms have given outsiders confidence in the system.

How to invest in Japan

If you want to diversify into Japanese equities as part of a broad allocation strategy, there are relatively easy ways for UK-based investors to do so.

If, like me, your Japanese is a little rusty, trying to stock-pick from a list of small and medium-sized companies is going to be very difficult, not to mention the tax problems associated with holding individual foreign shares.

Inevitably, then, most investors are going to take the funds route. The following funds are a representative sample of what is available on the market and are not an investment recommendation.

1) Japan-focused managed funds

Sometimes pairing investments across different fund classifications can make sense, particularly in terms of averaging out costs.Baillie Gifford Japanese Smaller Companies is the actively managed sister fund to Baillie Gifford’s investment trust and has an ongoing charge of 0.62%.

Investors looking for exposure to larger companies can opt for a value approach with Lindsell Train Japanese Equity. The fund is run to value investment principles with holdings of around 35 companies. The focus is on consumer goods, media and software companies, with low asset turnover being a prime objective so as to reduce costs.

2) Japan-focused investment trusts

Fidelity Japan Trust (LSE:FJV)has been going since 1994 and has a long-standing reputation for decent returns. The basic management fee is 0.70%, falling to 0.5% if the trust underperforms the reference index.

Baillie Gifford Japan (LSE:BGFD)was started in 1981 and is the second-highest performing investment trust, according to Citywire data, returning 24% over the past 12 months. The trust focuses on smaller companies with an above average potential for returns and so has a natural bias towards growth strategies.

3) Japan ETFs

Liquidity is always a consideration when buying exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and the iShares Core MSCI Japan IMI ETF (LSE:SJPA)ETF gives investors exposure to more than 1,200 stocks in the MSCI index, better than the TOPIX on its own. The management fee is a typically low 0.15%.

Further reading: a good English language introduction to Japanese equities is Japanese Equities: a Practical Guide to Investing in the Nikkei by Michiro Naito, published by Wiley.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.