Inside the Dragons' Den of Gervais Williams

18th September 2015 13:21

by Lindsay Vincent from interactive investor

Gervais Williams, something of a god of small things corporate, is not unlike one of those business people in Dragons' Den, the television programme where people with big ideas and small wallets go in search of capital from the show's principals.

Predictably, since this is the world of dreamers, many aspirants are weird, wacky or a waste of time. Even fewer have worthwhile, fundable ideas.

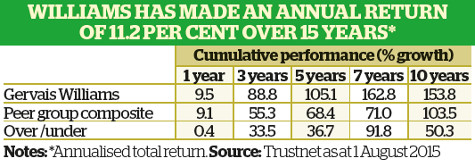

Williams, 56, who made his mark at Gartmore, a fund management firm now buried in the shifting sands of time, is today managing director at Miton, a firm at a formative stage, where he manages five of its investment vehicles.

Miton was assembled from bits of dismembered and defunct fund management groups such as Exeter Fund Managers. It has been an entity for some four years and now manages more than £2 billion, roughly half of which is in Williams's grip. He is a key shareholder in the enterprise.

The real diamonds stand out

The portals of fund management premises see a daily stream of suited men and fashionably dressed women arriving to present their wares and seek support. This is especially true of smaller and medium-sized companies.

"We see between 60 and 80 companies a month," says Williams - a flow that allows "the real diamonds to stand out". He adds: "We get more decisions right than wrong from these meetings."

One such Dragons' Den-type investment oddity is , a company that makes high-quality board and paper products from silver birch trees - but just the bark, not fibres from the trunk.

It is based in Finland, where there is rather a lot of silver birch. What makes its products different is their resistance to water, just the thing for packaging Farmer Giles's washed lettuce.

Williams was not a founder shareholder in Powerflute, but the business reflects his highly varied, innovative patch. A more mundane investment, , a Hertfordshire speciality brick-maker, illustrates his readiness to provide assistance to sound companies in need of critical support.

Williams backed its 2004 flotation but sold out ahead of the global financial crash. However, in 2013, with the company then heavily geared, he returned with a cheque in return for fresh equity. This lifeline allowed Michelmersh to fully participate in the housebuilding boom.

More recently, Williams also gave vital support to , a distributor of pneumatic and hydraulic parts. He describes the company as "a brilliant business that was starved of capital and had too much debt". He adds: "We bought equity and that allowed it to take out the debt. We are a large shareholder and are excited about the company."

The smaller company asset class, as many investors are aware, has proved the best long-term equity asset class, but, inevitably, the long-term proviso means some investors will die waiting for a reward. Minnows are especially vulnerable to the business cycle.

Yet, over the past decade - one that has seen the mother of all recessions - by one yardstick, the smaller companies sector was still the one to have been in.

The key figures have emerged from an analysis of the whole investment trust sector by Winterflood Securities. These show the total return from smaller companies trusts at the top of the pile, alongside Asia Pacific (excluding Japan) trusts.

However, crude numbers rarely tell the whole story. Much of the gain will reflect the narrowing of discounts to net asset value, an assured reality in stronger equity markets.

Sector for the specialist

Williams has a different perspective on what has been going on. "The past 30 years have seen a super-cycle of growth, but smaller companies have been a sideshow," he maintains.

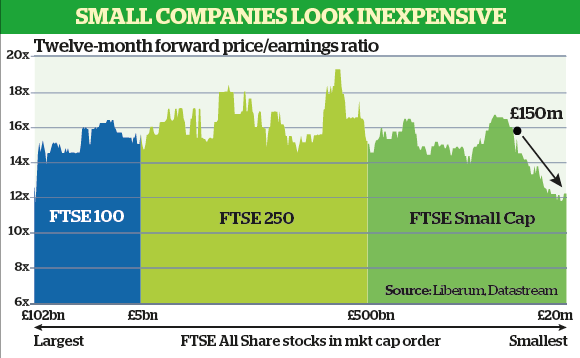

That they perform best over the longer term is well known, he says, yet some investors will say: "They are good, but so what?" Smaller companies peaked in 2014, he adds, "and then fell out of fashion". However, lately they have made something of a comeback as indices for larger companies have stalled.

Still, smaller companies will always be something of what Williams terms a sideshow, since a lack of liquidity makes many of them difficult to trade. With billions of investable capital at their disposal, institutional investors will always regard them as an irrelevance - even if there is money to be made.

Smaller companies is a sector for specialists, and Williams is undoubtedly one of the best-regarded, best-connected men in their ranks. He has sat on two government-run committees on quoted smaller companies and is currently a member of the AIM Advisory Council.

Today, he manages five funds, the largest of which is , worth some £450 million. This fund is a lookalike to the closed-ended fund , a top-quartile performer with assets of some £350 million.

The entities may be all but the same, yet the OEIC yields 3.8%; the investment trust, on a premium of around 2%, yields 2.6%.

The third fund, , has assets of less than £130 million and, as a fourth-quartile performer over the past 12 months, is the poor relation. But, as Williams readily points out, recent performance figures have picked up.

This improvement has proved timely, since in April, the Williams conveyor belt pushed out yet another small company vehicle - Milton UK Microcap Trust, a £50 million offering that has gained 8% since listing.

The trust is not a shadow of the smaller companies fund - itself 80% invested in micro-cap stocks, AIM-listed creations with capitalisations of below £150 million. The new investment trust is wholly invested in micro-cap stocks, but there is an overlap of some 50% in the portfolios of the two entities.

Williams is unequivocal about AIM. "We are lucky to have it," he says. "It is a vibrant and wide-ranging market." The two larger funds have 65% of their assets outside of big companies, he adds, as this is where he can add value.

Starved of finance

Williams casts his net widely. "My highest-conviction stock is only 1.5% of funds. We look to lots of smaller holdings coming right, rather than the odd 'scorching' performer, he explains.

What is common to all of Williams's target investment areas is their limited access to bank finance. The latest figures show that bank lending to industry is now on a rising curve but that smaller companies find it hard to borrow. Yet, he maintains, this state of affairs can be an advantage.

"This means smaller companies tend to have better balance sheets (with cash and no gearing). It also means relatively good productivity figures," he says. Williams cites one unnamed company as an example of the opportunities on offer. He says: "It is a tiny business with a price/earnings ratio of eight and a yield of 6%. I had no trouble writing it a cheque."

Williams says there are "stunning" valuations around. He adds: "The valuation gradient between big firms and micro-companies is the most extreme I have seen in 30 years." The downside is that "smaller companies rarely trade, and it's not always easy to sell".

Still, he has advantages over peers because of the way Miton manages its trading processes. "We are better able to sell," he says. The annual turnover of the Diverse Income Trust is some 25%.

Another reality for smaller companies is that investment analysis is hard to come by. The best analysts in top investment houses simply have better things to do with their time.

This, says Williams, means "a lot of smaller companies produce their own research and issue it through their brokers". He adds that such research "is not entirely independent", but offers "opportunities, as independent outsiders, for us".

One of Williams's top holdings is , an intriguing business that manages captive insurance companies, businesses that add to the brass plate count in places such as Hamilton, Bermuda. Captive insurance is self-insurance funded by companies operating and competing in the same line of trade.

"Charles Taylor is an outstanding business," says Williams, "and it manages about 25% of all captive insurance companies in the world. "Another insurance-related investment is , an upmarket, no win, no fee business.

He says it helps fund legal cases, usually small companies versus bigger companies, and takes a share of the settlement. About 90% of the cases it takes on have some resolution.

Beyond the realm of smaller companies, one of his largest investments is Provident Financial, a door-to-door lender with form at the Office of Fair Trading and National Consumer Council. Another familiar enterprise is , the Caribbean telephony operator. "This company is not well researched. It is a lovely business," he says.

Williams has one eye on the impending rise in UK interest rates, but he is not fretting about its arrival. "Higher interest rates will make it harder for companies to make money. We just have to find a way of making money despite these challenges."

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.