How to make money on big merger deals

There’s profit to be made in the middle of huge bids, like the one BHP recently made for Anglo American. Russell Burns explains how you might pull it off.

3rd May 2024 09:35

by Russell Burns from Finimize

- Merger arbitrage is a highly specialist trading area. But it usually provides steady, low-volatility returns that don’t rise and fall with the broader movements of the stock market.

- The potential takeover deal between BHP and Anglo American is just the kind of opportunity merger arbitrage traders look for. Their strategy is to bet on the deal’s completion.

- BHP is attracted to Anglo American’s copper assets, with AI data centres and the green energy transition expected to drive up demand for the metal. The Australia-based BHP has until May 22nd to increase its offer, but other firms could weigh in with offers of their own.

Some hedge funds do nothing but bet on the outcome of takeover situations – it’s what’s known as merger arbitrage. It’s not a mainstream route, and certainly not one that many individual investors take, but that doesn’t mean you can’t take a page from their specialised playbook and profit from it. Let’s look at how you might do it, starting with today’s most talked-about potential deal: BHP’s unsolicited proposed acquisition of Anglo American.

First, what do you need to know about merger arbitrage?

Well, there are a few key risk factors at play when looking at merger arbitrage, and you’ll want them on your radar.

Price. Obviously, this is the first (and maybe the biggest) factor. Takeovers can be friendly, but they can also be hostile. A friendly merger is when both companies have agreed to the terms and the price to be paid. These details are released with the official announcement. The offer price is usually struck at a higher (a.k.a. “premium”) level than the current share price to persuade shareholders to accept the offer.

If it’s hostile, then the parties haven’t reached an agreement. And the target company’s bone of contention is almost always that the price is too low, and materially undervalues the firm. That dispute can be resolved if the bidder is willing to increase the price – and that’s what often happens. See, the first bid often just tests the waters, and there’s often room for negotiation.

But once the news gets out that the company is a potential takeover target, another bidder may decide to get involved – and offer a higher price. If you’re a shareholder of the target company and another bidder appears, you’re sitting pretty: that usually means the stock is about to jump again and you’ll be able to sell at an even higher price.

Regulatory issues. These thorny details can doom the whole thing. Takeovers and mergers usually require the go-ahead from regulators, competition authorities, and other bureaucrats. The approval process can be quick and straightforward or drag on for months in some cases – like if the company operates in a politically sensitive industry or if the merger would limit competition so much that it might give the combined firm a monopoly.

Shareholder votes. Generally, no deal is getting done without the shareholders’ say-so. The bidding company will need to secure a certain number of votes – the percentage required varies depending on the country and type of transaction.

Material adverse clauses. If the target company’s business deteriorates sharply before the transaction is final, the whole thing can be unraveled by a material adverse clause. This is the bidder essentially saying, “this isn’t what I bargained for” and walking away.

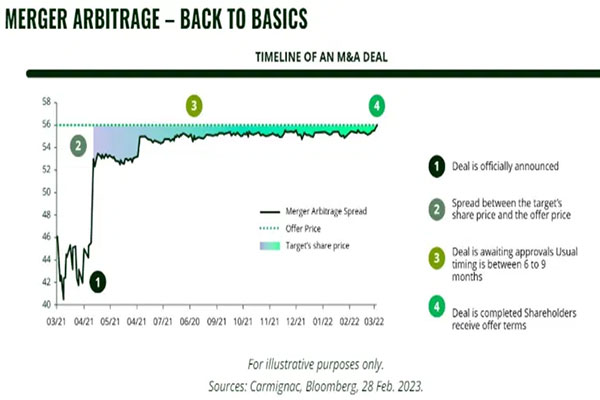

Now, the longer it takes the deal to complete and the higher the regulatory risks, the wider the gap on that potential deal price – called the spread or discount – and the more money that could potentially be made if the deal gets done.

Here’s a typical timeline and share price moves for mergers and acquisitions. Sources: Carmignac, Bloomberg.

When traders expect that a higher bid will materialise, they may send the share price higher than the current offer (it’s said then to be trading at a premium to the terms).

It’s worth pointing out that merger arbitrage returns come along with the M&A deals, and that means they defy whatever is going on in the broader stock market. An energy stock can rally on news that it might be acquired, even if the rest of the sector is falling. And that makes these stock plays a good portfolio diversifier. Your typical merger arbitrage fund manager could bring in annual percentage returns in the high single-digits in a good year, and the low single-digits in a bad year.

What’s going on with Anglo American?

BHP, the world’s biggest commodity company, announced a proposal last week to buy UK-listed Anglo American in a £31 billion ($38 billion) all-stock deal.

Anglo owns a range of commodities, including copper, iron ore, platinum, coal, and manganese. BHP offered to pay shareholders roughly 0.7 shares of BHP for each share of Anglo American. Before completion, the Australia-based BHP would distribute the shares held by Anglo – in South African-listed Anglo American Platinum and Kumba Iron Ore – to existing shareholders.

See, it’s the high-quality copper mining assets that BHP is after – and if it sells the iron ore and platinum assets – it reduces the overall cost of the acquisition.

The total value was worth £25.08 for each Anglo American share. Anglo’s stock initially rallied 16% to £25.60, a small premium to the terms, but a premium nonetheless. The company rebuffed the deal, saying the terms “significantly undervalues” Anglo – and then major shareholders and the South African government got pretty vocal too, saying the price was far too low.

And you could say they’ve got a point. Copper is expected to see a huge demand pick-up from AI data centers and the green energy transition. Anglo’s got copper in spades and that’s valuable: it’s hard to find and develop new copper mines. BHP – already one of the top copper miners in the world – sees Anglo as a big supply solution. Buy, don’t build.

And that view has probably not changed. Despite that first rejection, traders expect BHP to come back to the table with a higher bid. And if, for some reason they don’t, other companies like Rio Tinto or Glencore might well be thinking this as a too-good-to-miss opportunity. See, once a company is in the shop window – others will take a closer look and may decide to get their wallets out.

And it won’t just be potential acquirers checking Anglo out. Activist investor Elliott Management disclosed last week that it had a £1 billion ($1.2 billion) holding in the miner – and traders think that even if a takeover doesn’t happen, pressure on Anglo’s higher-ups will build and push them to make some value-enhancing strategic decisions – maybe spinning off some plum assets. And that probably means that Anglo’s share price will stick above pre-bid levels – even if no new bids emerge.

What’s the trade, then?

Anglo American’s share price is currently trading around £26.70 ($33.40) – about 6.5% higher than the initial bid.

Takeover rules in the UK mean that BHP has until May 22nd to make a better offer. Basically, this is “put up or shut up” time.

What you decide to do here will depend on your appetite for risk. But for the moment the best two trading strategies would appear to be:

Buy Anglo American shares. This works on the assumption that BHP will return with a sweeter offer – or that another company will sweep in and spark a competitive bidding auction. With new bids at play, the stock could see a gain of, say, 10% to 20%, which is pretty nice. Then again, if no new bids materialize, the stock could fall by a similar amount.

Avoid the situation altogether. Instead, take advantage of the shortage in copper supply that could be looming. You can do that through the iShares Copper and Metals Mining ETF, or, if you live outside of the US, the iShares Copper Miners UCITS ETF GBP (LSE:MINE). Alternatively, you could invest directly in one of the ETF’s biggest holdings: Freeport McMoRan or Antofagasta.

Or short Anglo American. If you think there won’t be a higher bid from BHP or anyone else, then you’re probably expecting Anglo American’s share price to fall from here. So you could consider shorting that stock – borrowing Anglo shares and selling them into the market – with the expectation of profiting by buying them back at a lower price. [this option is not available on the ii platform]

Russell Burns is an analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.