How Daniel Kahneman’s genius can help you become a better investor

With his precise understanding of human behaviour, the Nobel laureate knew all the mistakes you’d make (even before you made them). Here's what you can learn.

5th April 2024 10:27

by Stéphane Renevier from Finimize

- Daniel Kahneman understood how the human brain works and the fact that it operates on two modes of thought. There’s System 1, which is quick, instinctive, and often emotional, leading to immediate reactions like buying a stock on impulse because of FOMO, and there’s System 2, which is slow, deliberate, and analytical, leading to more thorough evaluation before making investment decisions.

- The first step to becoming a better investor is to understand when system 1 dominates (in uncertain, high-stakes, or complex scenarios), and to be able to identify your cognitive errors, emotional reactions, and belief reinforcement biases.

- The next step is to engage system 2 more, by using checklists, keeping an investing journal, playing your own devil’s advocate, calculating base rates, simplifying investing, and maintaining a clear investment process.

The key to a successful portfolio might be in making perfectly informed, cool, calculated decisions. The problem is, investors are human beings, prone to abandon rational thinking and opt for emotional conclusions instead.

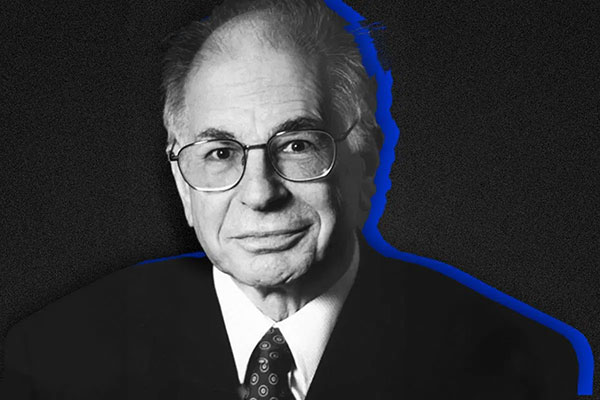

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman understood this better than anyone: a founder of behavioural economics, he could clock every one of your biases and decision-making flubs, before you even made them. Kahneman died last week at age 90. So, in honour of his genius, let’s take a look at the wisdom he left behind – and how you can use it to become a far smarter investor.

Basically, your brain operates on two systems.

Kahneman’s exploration of human cognition revealed two distinct modes of thinking that profoundly impact decision-making, which he outlined in a best-selling book, Thinking, Fast And Slow. He found that the brain has two systems:

System 1 is your brain’s fast, automatic, intuitive gear. Imagine it as your gut reaction, the instinctive decisions you make without even realizing it. It’s like seeing a stock’s price spike and feeling an immediate urge to buy, driven by a fear of missing out (FOMO). System 1 is efficient for everyday decisions that don’t require deep analysis. However, when you’re investing, it can lead you to make hasty, emotion-driven decisions – often to your detriment.

System 2 is your brain’s slow, deliberate, analytical device. It’s the voice in your head that says, “Hold up: let’s think this through”. When you’re considering an investment, System 2 prompts you to dig into the financials, consider the market context, and weigh the potential risks and rewards. It requires effort and energy, but it’s your best bet for making informed, rational investment choices.

If you want to become a better investor, Kahneman’s research lays some important groundwork. If you can learn to understand System 1 really well, you can recognize when it’s in control and identify its potential biases. And, you can teach yourself to engage System 2 more.

System 1: Know your enemy.

System 1 works all the time, but it tends to take the leading role in situations where there’s uncertainty, high stakes, emotional stress, complex information, or a group dynamic. Yes, that means pretty much every time you need to make an investment decision. Certain scenarios, though, really put System 1 to the test, like investing in highly disruptive technologies (high uncertainty), planning for retirement (high stakes), choosing what to do during a market correction (emotional stress), forecasting earnings (complex information), or exchanging views with your peers.

Of course, understanding when and why System 1 might lead you astray is only half the battle. You also need to recognize your mental shortcuts and biases for what they are. Luckily, Kahneman – and his research collaborator Amos Tversky – shed light on all those cognitive quirks. Here are some of them.

Cognitive errors

These biases arise from basic human brain limitations or errors in reasoning and information processing.

Availability heuristic. Think investing in bitcoin sounds like a stellar idea because everyone on your feed is doing it? That’s your brain taking a shortcut, confusing “easy to remember” with “likely to succeed”.

Representativeness heuristic. Spot a young company with rocket-like growth and immediately dub it the next Apple? That’s your brain oversimplifying, mistaking a good story for a sure bet – without checking the fundamentals.

Anchoring and adjustment. Ever cling to the last price of a stock before it dropped? That’s your brain anchoring – getting stuck on initial impressions or specific levels, and then struggling to adjust.

Emotional reactions

These biases are primarily influenced by emotional responses.

Prospect theory. Ever notice how losing £500 stings more than winning £500 feels good? The brain is wired to fear losses more than it values gains, making humans odd risk assessors, by nature.

Endowment effect. Holding onto an underperforming stock because you picked it? That’s the endowment effect – a tendency to overvalue what you own, just because it’s yours.

Belief reinforcement

These biases reinforce or justify pre-existing beliefs, often in the face of contradictory evidence.

Overconfidence bias. Convinced you’ve got the Midas touch after a few investment wins? Careful, that’s overconfidence. Your record may not be as golden as you think, because the brain tends to underestimate the role that luck plays in the short term.

Hindsight bias. Convinced you knew that market crash was coming all along? That’s hindsight bias – the brain’s ability to make you believe you’re Nostradamus after the fact.

Optimism bias. Feel certain that the earnings of your favourite stock will keep growing at the current high rates for years to come? That’s optimism bias – most people wear rose-coloured glasses when predicting their financial future.

Confirmation bias. Only tuning into news that backs up your bullish or bearish stance? That’s your confirmation bias at play – ignoring or discarding any info that doesn’t fit into your narrative.

System 2: Contain your enemy.

Alright, so you’ve come to grips with your biases, but – be careful – that doesn’t mean they’ve packed up and left. The goal now is to limit the impact of those stubborn impulses and give your analytical side, System 2, the upper hand.

Here are a few practical things you can do to make that happen:

Run through checklists when you’re making investing decisions. They can help you tackle your brainwork head-on. General questions like “Can I prove that I’m making this decision with solid logic, not the predispositions mentioned above?” or bias-specific ones like “Would I buy this stock today if I didn’t own it?” can save you from facepalm-inducing mistakes.

Understand yourself better through journaling. Keep a diary of every investment move, jotting down why you’re making each decision, how you feel, and what the market mood is like. Those little notes can be like a mirror, showing you the real face of your decision-making process.

Play devil’s advocate against yourself. Dive into views that clash with yours. Flipping the script and arguing against your own stance can unveil blind spots you never knew you had. Or conduct a pre-mortem analysis of your view or trade, imagining it’s a future date, you were wrong, and identifying as precisely as possible the potential reasons for failure (including both fundamental and psychological factors).

Have a clear, rule-based, investment process. Spell out your game plan – what you’re chasing, what terrifies you, where you’re looking for ideas, your personal no-go zones, your entry and exit strategies, and how you’re spreading your bets. The more rules you have, the less room for your biases to intervene. And make sure you do it in advance: A rulebook crafted in calm waters can keep you from making waves when a bad storm hits.

Try to calculate the “base rate”. Learn to balance “inside views” (subjective judgments and narratives) with “outside views” or the “base rate” (objective, hard data) in your forecasting. By starting with the objective likelihood of events based on historical data and then adjusting for unique factors of the current situation (the inside view), you can make more accurate predictions while avoiding the biases that often skew subjective judgment.

Make investing as uncomplicated as possible. Simplify, simplify, simplify. A straightforward, hands-off strategy means fewer chances for biases to butt in. You should also diversify to avoid putting all your eggs in one unpredictable basket.

Profit from the biases of others. Consider adopting strategies that benefit from other investors’ biases, like value, or trend-following. Value investors take advantage of people reacting too strongly to bad news, focusing too much on available information, sticking too closely to their first impressions, being overly confident, overly optimistic, or overly fearful of losses. These mistakes lead investors to pay too much for popular growth stocks and too little for less-exciting value stocks. On the other hand, trend-following aims to capitalize on these errors by going along with emotionally driven market trends for as long as they last.

It may take some trial and error, but the more you tune into the way your brain works, the more you’ll understand why other investors behave the way they do – and the more opportunities you’ll find along the way. And most importantly, it might help you tame your worst enemy: yourself.

Stéphane Renevier is a global markets analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.