How is AI going to change the economy?

We analyse the potential impacts of artificial intelligence on economic growth and productivity, jobs and wages, sectors, government policy and regulation, and geopolitics.

22nd September 2023 13:36

by abrdn Research Institute from Aberdeen

Key Takeaways

We are cautious optimists on AI’s eventual productivity impact. The lack of a measurable impact thus far is not a good reason to downplay its potentially transformative effect. Previous general-purpose technologies have taken time to raise productivity.

Economic history suggests that job creation and productivity enhancement from technological change more than outweigh job destruction over the long run. That said, one risk is that the scope of job types under threat from AI means this time could be different.

Certain sectors will be outsized beneficiaries from AI. In the near term, these are ‘enablers’ like chip manufacturers, ‘scalers’ such as platforms, and ‘early adopters’. In the long term, those with large numbers of knowledge workers and lots of administration, such as finance, education and the law, are the biggest beneficiaries (from the perspective of capital).

Governments and regulators face a pacing problem whereby the rate of innovation is so rapid that policy struggles to keep up. We anticipate a wave of AI regulation, focused on human oversight, accountability of decision-making, privacy, and bias.

Finally, AI hardware and software will become a new locus of geopolitical competition. Export bans of leading-edge graphics processing units are already part of the arsenal of US-China rivalry. The values embedded in AI decision making, and its dual-use military and commercial applications, raise the prospect of a cyber arms race.

The promise and perils of AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the simulation of human intelligence by machines, including understanding natural language, making decisions, recognising patterns, learning from experience, and solving complex problems. This includes machine learning and neutral networks, natural language processing and generative AI, and computer vision and robotics.

The AI revolution is dominating conversations about long-term growth, structural economic change, the types of jobs people will do and the skills they need to have, and the corporate winners and losers from this change.

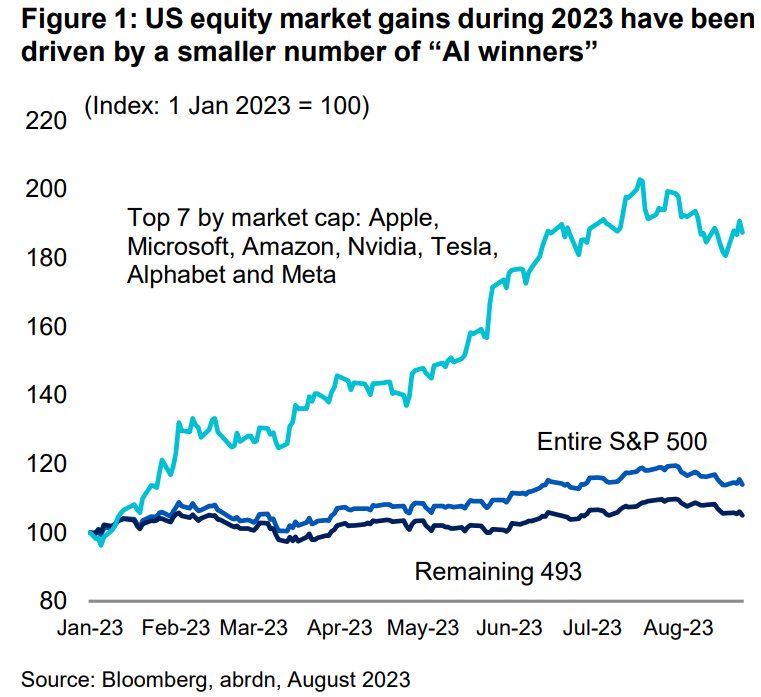

Indeed, increasingly pervasive products and services are already changing consumer experiences and corporate processes. Meanwhile, US equity market performance over the past year has been driven by a narrow number of “AI winners” (see Figure 1).

Unlocking higher productivity paradigms?

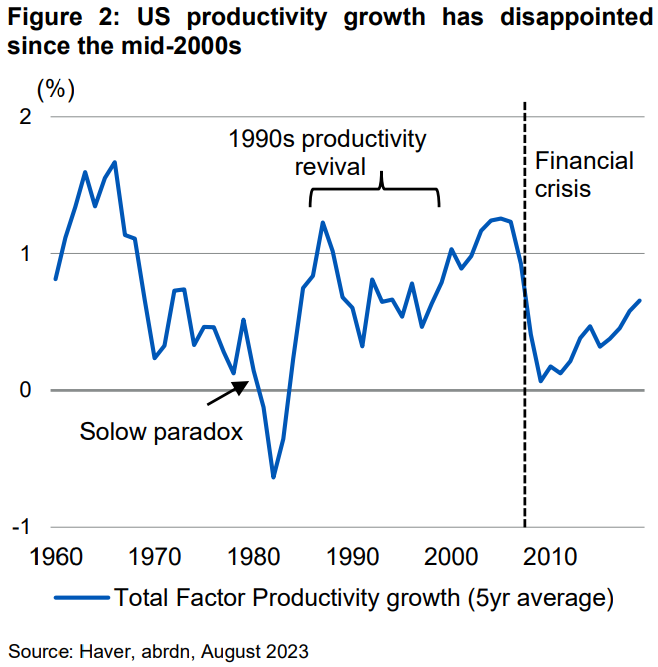

Developed economies have been stuck in a period of low productivity growth since the global financial crisis (see Figure 2). This has been attributed to exhausting the low-hanging fruit of past innovations, stagnating educational attainment, fewer spillovers from globalisation, a more intangible economy, demand deficiency and a lack of investment, and mismeasurement.

Meanwhile, technological changes of the past few decades, including smartphones, e-commerce, cloud computing, the internet of things, and now AI, have had limited impact on measured productivity growth.

But this is not surprising, and shouldn’t be extrapolated to mean a productivity boost from AI is not coming.

The “Solow paradox” referred to the absence of a measurable productivity boost from the computer revolution (the “Third Industrial Revolution”) of the 1970s and 80s – which then showed up in the 1990s. Before that, electrification and the internal combustion engine in the late 19th century’s Second Industrial Revolution didn’t show up in the productivity data until after World War One. It takes time for innovations to diffuse into widespread use.

Indeed, this delayed but eventually transformative impact appears to be a hallmark of a “general purpose technology”, or GPT (not to be confused with a Generative Pre-trained Transformer of the ChatGPT variety!). AI also shares many of the other features of a GPT – pervasiveness, continuous improvement, and innovation spawning. There are too many potential labour-saving and augmenting applications, over too many domains, to not have an impact on long-run productivity growth.

We are therefore cautious optimists on the eventual positive productivity impact from AI. While our long-term paradigms cite “back to the new normal” as the baseline, our next most likely paradigm is “productivity rebound”.

Does higher productivity mean higher wages?

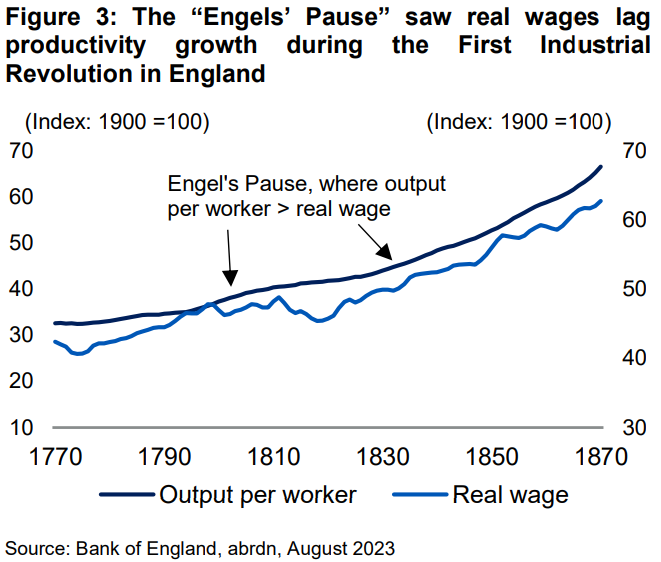

Productivity growth is a necessary rather than sufficient condition for higher real wages. It is possible to have long periods of productivity growth without an increase in wages.

This famously occurred during the early First Industrial Revolution, when, from 1800 to 1820, productivity increased as a result of steam power, railways and the telegram, but real wages stagnated (see Figure 3). This period is referred to as “Engels’ pause”, where the gains from higher productivity accrued almost exclusively to the owners of capital.

So, it is plausible that even if AI delivers huge productivity gains akin to another industrial revolution (the “Fourth Industrial Revolution”), those gains could be extremely concentrated.

The outcome will ultimately turn on the impact of AI on the labour market and the social institutions that mediate the distributional consequences of economic change.

Creating new jobs, enhancing existing ones, or replacing humans entirely?

On the labour market front, it is helpful to distinguish between three effects that technological adoption could have on employment: job destruction, productivity enhancement, and job creation.

Job destruction is the effect that typically gets the most attention. In particular, there is a growing sense that generative AI will automate “white collar” or “creative” jobs that were previously thought beyond the reach of “machines”.

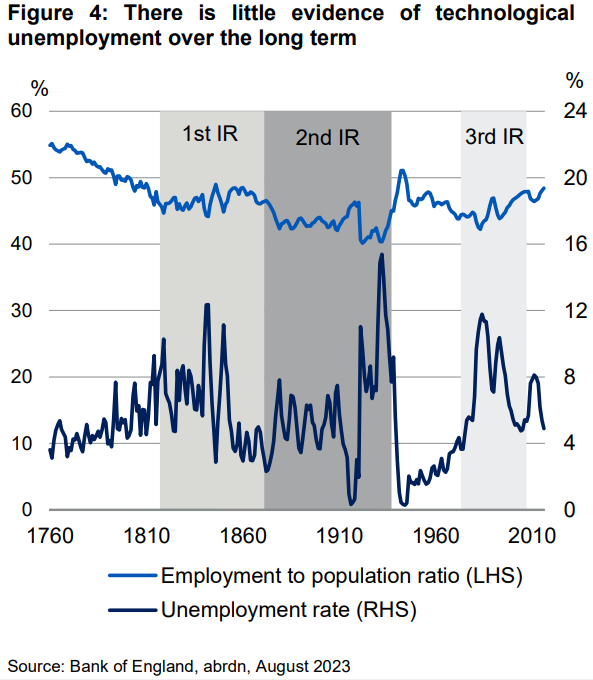

The widespread adoption of AI will almost certainly lead to some job destruction. But in the long sweep of history, there is very little evidence of sustained technological unemployment.

Swings in aggregate demand result in cyclical fluctuations in employment, but it is very hard to see any impact from technological change in the average rate of employment despite the many types of jobs destroyed by successive innovations (see Figure 4).

This is because the combination of productivity enhancement and job creation has historically been much larger than job destruction.

We’ve already argued for a positive productivity impact from AI. But the adoption of new technologies also helps create new jobs. These might be directly linked to the new technology – for example, training AI models – or in completely unrelated sectors that emerge as a result of the new spending power created by higher productivity.

Sectoral impacts will not be distributed evenly

Even in the best case scenario, there will be some sectors severely damaged by AI, while others will benefit hugely. In the near term, we think the winners will fall within three categories: ‘enablers’ like chip manufacturers, ‘scalers’ such as tech platform businesses, and ‘early adopters’ such as software companies.

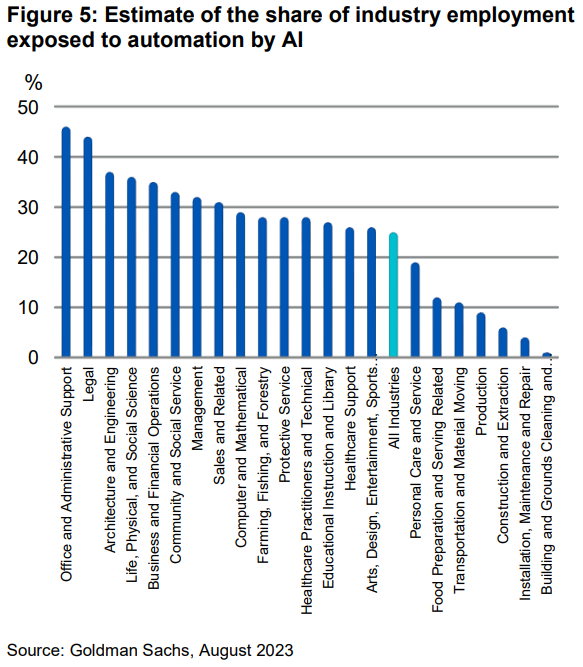

In the long term, sectoral effects are more speculative and will depend on the way the technologies are regulated. But winners (from the perspective of capital owners) are likely to be sectors with large numbers of knowledge workers like finance; administration-heavy sectors such as education, healthcare, and the law; and those with technical but repetitive tasks such as high-end manufacturing.

By contrast, labour in these sectors could be under significant pressure (see Figure 5). By contrast, sectors with a seemingly lower ability to increase productivity using AI include manual and outdoor labour, the hospitality sector, and personal care. That said, “dumb” automation and self-service are all potential productivity enhancers in these sectors

Governments and regulators have a lot of catching up to do

The institutional arrangements under which the adoption of AI will take place are crucial. Norms, laws, and taxes all shape the pattern of income and wealth distribution.

These social processes are in part endogenous to economic outcomes. Trade unions and friendly societies arising from the First Industrial Revolution were a response to the perceived inequality of the “Engels’s pause”.

In turn, those institutions helped bring that period of stagnating living standards to an end.

Similarly, new institutions and regulatory frameworks will need to be developed in response to the impact of AI. However, governments may face a “pacing problem” whereby the rate of innovation is so rapid that policymakers struggle to keep up.

AI regulation is still at a very early stage. The European Commission is negotiating with member states to seek approval for a draft AI Act, which would be the first comprehensive AI law. The UK government is at an earlier consultative stage, while in the US the White House has introduced a non-binding “AI Bill of Rights”.

The outcome of all three regulatory frameworks will be affected by elections next year, including European Parliamentary elections in summer 2024, and UK and US elections in autumn 2024.

These nascent regulatory efforts are focused on human oversight of autonomous systems, responsibility for AI decision making, transparency of decisions, privacy, and bias. We anticipate a wave of AI regulation over coming years, although different countries will strike different balances between the strength of regulation and incentives to innovation.

Because transformative innovations are by their nature hard to predict, it is unlikely that childhood education systems can equip future workers for all the appropriate skills demanded by the future labour market. Instead, adult education and retraining is likely to be especially important to help workers acquire the necessary skills and help displaced workers find new work. A flexible labour market combined with a generous safety net could be the institutional arrangement that countries gravitate towards.

Indeed, higher rates of taxation on capital and even a “citizen’s income” are potential tools to more broadly distribute the gains to capital and ameliorate the potential harm to labour’s share of income from AI.

The geopolitical angles

Given the likely economic significance of AI, its many dualuse (military and commercial) applications, and the location of leading-edge hardware production, the AI revolution is also likely to have a significant geopolitical angle.

The training and running of AI systems relies heavily on the most advanced graphics processing units, which are designed in the US and built in Taiwan by a very small number of firms. This geographical and firm-level concentration means hardware production is already being used as a tool of geopolitical influence, for example via controls by the US and its allies on exports of advanced chips to China. More speculatively, blockades or military action that threatened chip exports from Taiwan could significantly impede AI development globally.

The development of AI software may also become something of a cyber arms race. The physical location of software developers, and the location and security of intellectual property, is likely to be politically sensitive. We are starting to see this play out, with the UK’s decision to include China in its forthcoming AI summit in November criticised by Japan, the US and the EU. But the more diffuse, mobile and intangible nature of AI software, as opposed to the hardware on which it runs, means governments’ ability to exert control is more nebulous.

Finally, the values embedded in AI decision making (for example, around gender or ethnicity), and the uses to which AI is put (for example, surveillance, political influence, or even battlefield use) are all likely to vary between countries. There are initial efforts at international co-ordination on these issues, such as via the UN’s “AI and global governance platform”. But the fractured global economic and political system means countries are likely to pursue “digital sovereignty”.

Written by Paul Diggle, Chief Economist at abrdn, and Senior Economist Luke Bartholomew.

abrdn's Research Institute produces original research at the intersection of economics, policy and markets.

ii is an abrdn business.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.