Global Economic Outlook: after the hikes

What happens after the hikes? As many central banks ponder cutting interest rates next year, we look at the diverging paths of the main economies. Read on to find out more…

8th December 2023 09:54

by abrdn Research Institute from Aberdeen

Resilient growth and moderating inflation in the US reflect positive supply shocks that are almost exhausted. We forecast a slowdown and then a mild US recession from mid-2024 onwards.

European economies are already weak, and we expect them to remain so until the middle of next year, although positive real income growth should limit this downturn.

Most central banks have finished hiking interest rates and should begin cutting them in 2024 as inflation fades further.

China’s recent policy easing is now stabilising economic activity, but there are still long-term headwinds to growth. Emerging markets elsewhere are benefiting from weaker inflation, and they are entering a cycle of lower interest rates.

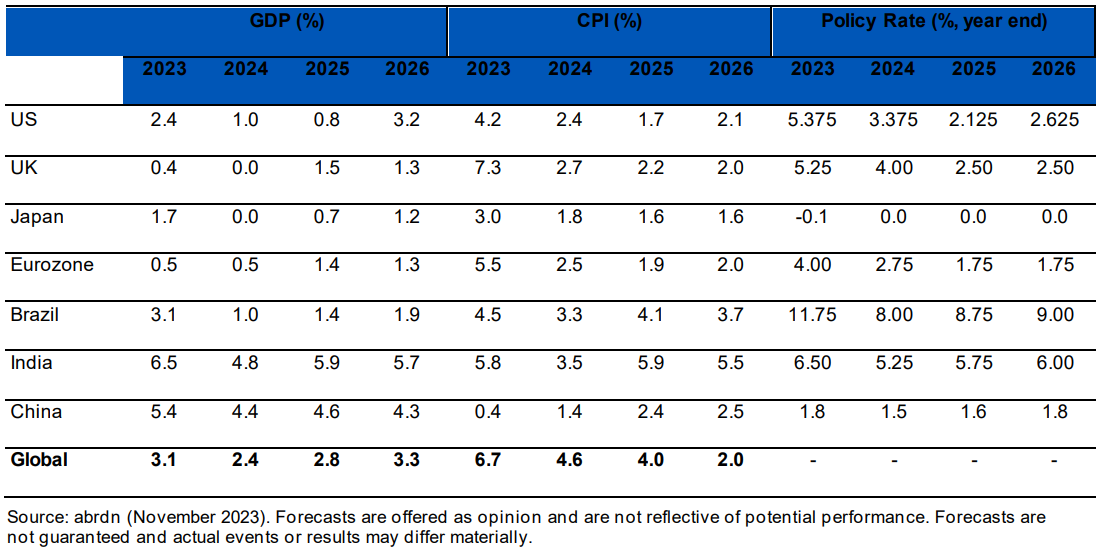

Figure 1: Global forecast summary

US strength abating

Robust US economic activity, along with moderating inflation, have further increased the probability of a ‘soft landing’ – the prospect of inflation back in check while avoiding a recession.

This favourable growth/inflation trade-off is the result of positive supply shocks – rising labour-force participation, improved labour-market matching, unwinding global supply-chain pressures, falling energy prices, and higher productivity growth.

But in our base case – our ‘most likely’ scenario – we think these improvements may now be largely exhausted. Meanwhile, household savings buffers are close to being used up, which, alongside tight credit conditions, should see US growth slow. Activity already seems to be moderating from the strength seen in the third quarter, amid slower payrolls growth and falls in purchasing managers’ indices.

In fact, the recent rise in unemployment is close to triggering the Sahm rule – a 0.5 percentage-point increase in the three-month average of the unemployment rate over a year has always been associated with recession. While this time might be different due to strong supply rather than demand weakness driving the increase, other medium-term recession signals are still elevated.

Despite the sharp moderation in headline US inflation, underlying inflation pressures are not back to target levels. While we think the Federal Reserve (Fed) has finished raising interest rates, it may not be able to cut them until it’s too late. That’s why we continue to expect a mild US recession and Fed rate cuts from mid-2024 onwards.

Mild recession in Europe

By contrast, economic stagnation or small contractions in the Eurozone and UK reflect standard business- cycle dynamics following a period of rate hikes. That said, activity surveys have recently shown signs of stabilisation, and real-wage growth has turned positive. This should keep European recessions mild and help drive the recovery later next year.

Headline inflation in Europe has declined substantially due to slowing increases in energy and goods prices and economic weakness. But, with wage growth still well in excess of inflation targets even after adjusted for productivity growth, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) are unlikely to start cutting interest rates until mid-2024 despite this period of economic weakness.

Interest rates going lower

As and when interest-rate cutting cycles begin, we think these will be more rapid, and reach a lower level, than financial markets expect. This reflects our view that so-called ‘equilibrium’ policy rates, or r*, will remain low amid ongoing structural headwinds and fading pandemic-era distortions.

But while r* is still low, the risk premium that bond investors demand may keep bond yields structurally higher than before the pandemic, even if they settle lower than they are today. Large deficits at a time when economies are beyond full employment and interest rates are high have increased concerns about the health of government finances.

While we do not forecast fiscal crises, the fiscal impulse – the extent that taxation and government spending can affect an economy – will turn more negative. Fiscal policy has little room to loosen in any downturn. In addition, changing central bank balance sheet policy, especially in Japan, means the anchor on bond yields from stimulus policies such as quantitative easing and yield curve control (YCC) is fading.

Indeed, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is a notable outlier among the developed markets, as we now expect it to marginally tighten policy further. The BoJ may feel comfortable enough about underlying wage growth to exit YCC, and end a prolonged era of negative interest rates, in 2024.

That said, with higher inflation expectations only weakly embedded, Japan may only swap negative rates for a long period of zero rates.

EM stabilisation

Chinese activity data are now bottoming, and 2023 economic growth should beat the government’s 5% target. While this is partly thanks to statistical revisions, policy support is gaining traction, and we think additional fiscal stimulus and property support is coming.

Negative inflation in China is being driven by temporary factors including volatile pork prices. It should rise soon, even though underlying inflation remains subdued. China’s economy faces structural headwinds, including from a battered real estate sector. That’s why our 2024 forecast is marginally below consensus. However, pessimistic long-term comparisons with Japan are wide of the mark.

Meanwhile, headline inflation in other emerging markets (EMs) should continue to fall rapidly. Underlying inflation pressures in those markets are receding amid tight monetary conditions, softer growth, and favourable base effects.

While El Niño-driven food-price volatility and possible energy-market shocks continue to be risks, a broader EM easing cycle can begin in mid-2024, especially given the high starting point for real interest rates in EMs.

Political uncertainty

Political risks will be heightened during 2024, given the large number of important elections scheduled and existing geopolitical tensions.

In the US, opinion polls now marginally favour ex-president Donald Trump over the incumbent, Joe Biden. Trump may have less scope to cut taxes given a likely split-Congress and the size of the US deficit. Alongside proposals to increase trade tariffs, this could make another Trump term more challenging for investors.

There are also downside economic risks from an escalation of conflict in the Middle East and a surge in oil prices, although we give this scenario a low probability given diplomatic efforts.

Upside risks to the global economic outlook are primarily from a US soft landing, a scenario which has become more likely.

Written by abrdn Research Institute

ii is an abrdn business.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.