Fundsmith Equity just keeps growing, but how big is too big?

We explain why funds can become too big, and consider the size of Fundsmith Equity.

22nd January 2021 09:33

by Kyle Caldwell from interactive investor

We explain why funds can become too big, and consider the size of Fundsmith Equity.

When outsourcing the investment decision-making to a professional stock-picker there are various things for investors to consider. Most important of all is to know what you are buying by swotting up on how the fund manager invests.

The size of the fund is a less obvious statistic to be drawn to when reading the fund or trust factsheet. This is a two or three-page document giving investors a quick overview of where the fund is currently investing, the top 10 holdings and the investment objective.

But it is important to consider size, particularly when a fund has many billions of pounds of assets under management.

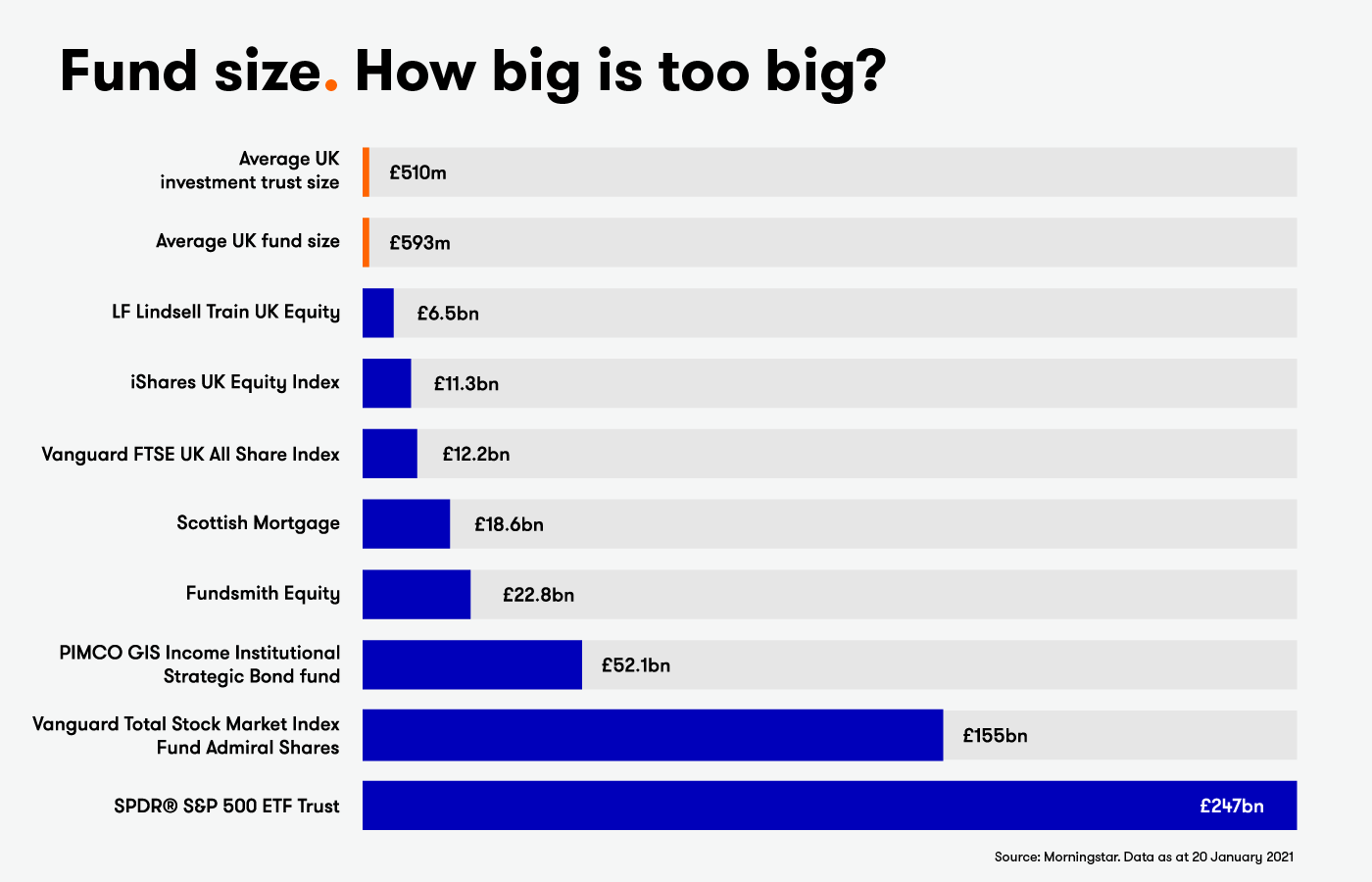

Fundsmith Equity, for example, managed by respected investor Terry Smith, has seen its fund size notably grow over the past couple of years. At the end of last month, it had £22 billion in assets compared to £13 billion just three years ago.

The UK’s largest investment trust, Scottish Mortgage (LSE: SMT), a member of the FTSE 100 index, has also seen a huge increase of assets of late. According to investment trust analysts at Investec, the market capitalisation of Scottish Mortgage has over the past year increased from £8.5 billion to £17.6 billion. It’s risen even further since they compiled these stats.

- Fund spotlight: Fundsmith Equity

- What to invest in when getting started: a beginner’s guide

- ii Super 60 investments: quality options for your portfolio, rigorously selected by our impartial experts

Investments trusts vs funds

The first thing to point out is that for investment trusts with a large amount of assets, size is not an issue. With investment trusts, a fixed number of shares are issued, raising a fixed amount of money for the manager to invest in a portfolio of assets. Those shares are traded on a stock exchange and their price fluctuates according to demand and supply. But the fund manager does not have to sell or buy shares depending on whether they are attracting or losing investors.

In contrast, funds must invest when they receive inflows of cash, or sell investments held in the fund when there are more sellers than buyers asking for their money back at the same time.

Tom Becket, chief investment officer of Punter Southall Wealth, describes inflows into a fund as “a positive feedback loop” and outflows “a negative feedback loop”.

When a fund is performing well, the addition of new money is usually a good thing, he points out, as the fund manager has more cash to invest to buy more shares in existing holdings in the fund. In a rising market, this could prove beneficial in terms of performance.

There is such a thing as too much cash

It is much easier to invest new money coming into a fund when there is a steady amount of inflows each month, rather than a large inflow all at once. Under the latter scenario, it could be trickier for the fund manager to quickly invest the money – although, as I explain later, it depends on what the fund invests in. If the fund manager cannot invest the money quickly, performance in a rising market can be compromised by having a bigger cash position.

A sustained period of investor outflows can have the reverse effect. Here, the bigger the fund becomes the more sizeable the potential outflows could be.

Becket says: “The size of a fund becomes a concern when things start going against a fund manager. If the style of the fund, in terms of the way the fund manager invests, goes out of favour or if performance becomes more sluggish for a separate reason, then this can then lead to investor withdrawals.

“When this happens, the fund manager has to raise cash to redeem investors by reducing or selling some of its underlying holdings. This is a headwind that negatively impacts fund performance as the fund manager is having to sell when they may not want to.”

When selling is the hardest thing to do

For funds that invest in large global companies that are liquid (easy to buy and sell), meeting investor redemptions is usually not a problem. The opposite, however, is true when a fund invests in illiquid companies that are harder to sell, such as unlisted companies, which led to the downfall of Neil Woodford.

But for the biggest funds, even if they invest only in large companies, selling down holdings can be a trickier exercise compared to funds with a smaller amount of assets. This is because big funds have larger stakes in companies. Smaller funds are nimbler, so in theory can buy and sell quicker.

Adrian Gosden, who formerly co-managed a fund with a large amount of assets (Artemis Income), and is now manager of the GAM UK Equity Income fund, has previously pointed out: “Running a big fund means having bigger stakes in companies, and you can end up being the biggest shareholder. If you want to sell, the market can work out that the biggest shareholder is selling [and that causes the share price to fall as other investors sell too].”

Big fund, less choice

In addition, as a fund grows in size the investment universe becomes smaller. Funds with billions of pounds of assets cannot buy shares in smaller companies for two reasons.

The first is the potential liquidity risk of not being able to sell easily when owning a large stake in a smaller company. The second, is that even a large stake in a small company would not be significant compared to the size of the fund, so the impact on fund performance would not be meaningful.

Again, it is a case of looking under the bonnet and understanding how the fund invests and what its main objective is.

Some funds that are set up to invest in smaller companies grow so big they can invest only in the largest of the smaller companies sector. They may even widen their exposure to include medium-sized companies in the FTSE 250 index. This can be a cause for concern as the fund manager is straying from their original remit and has a hand tied behind their back.

Here’s what Terry Smith told interactive investor

In the case of a fund that invests in large global companies, such as Fundsmith Equity, fund size is less of a concern. Terry Smith has, on a number of occasions, addressed the growing size of the fund. The average market capitalisation of the fund’s 30 holdings is £147 billion, way above the £22 billion in assets the fund holds. Smith has pointed out that if the fund held 1% in each, it would be over £40 billion.

With regards to whether the list of investment opportunities has shrunk due to the growing fund size, Smith told interactive investor: “It hasn’t ‘shrunk’ in the sense that our investable universe of stocks we would be willing to own has not declined in size. But we can no longer invest in a $2 billion market value company like we did with Domino’s Pizza at the outset of the fund, or we would have an illiquid position in the stock and we have always been alive to the risk of combining illiquid holdings in an open-ended daily dealing fund.

“But it is easy to lose sight of the fact that just as our fund has grown in size, so have some companies. We could still invest in Domino’s today as it’s now a $15 billion market value company. For smaller and newer companies, we set up the Smithson Investment Trust (LSE:SSON) which can invest in smaller companies than the main Fundsmith Equity Fund and has no liquidity issues.”

- Income prospects for 2021: fund and trust tips

- Three income trusts the pros are picking for 2021

- Take control of your retirement planning with our award-winning, low-cost Self-Invested Personal Pension (SIPP)

A final point to make is that taking larger stakes in a company can result in giving a fund manager greater access to company management, as well as being able to exert influence.

James Anderson, fund manager of Scottish Mortgage, notes the growth in its assets has helped “build our underlying competitive advantage” in terms of the level of engagement he and his team have with company management. “In that context, scale is a virtue rather than a hinderance.”

So, how big is too big?

In summary, funds become too big when they can no longer fulfil, or stray from, their remit. It is important to look under the bonnet and assess whether the growing size of a fund has changed the way the fund manager invests. If, when the fund had a smaller amount of assets the fund manager was investing in smaller companies, but this has now changed due to its fund size increasing, it is a warning sign that the fund has become too big.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.