Castings: a reliable cash-rich crisis survivor

It ended the financial crisis on top and will likely survive the pandemic and its economic fallout.

10th July 2020 15:31

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

It ended the financial crisis on top and will likely survive the pandemic and its economic fallout.

In the year to March 2008, as the Great Financial Crisis loomed, Castings (LSE:CGS) was well prepared. It went into the crisis highly profitable and cash rich, and it emerged highly profitable and cash rich.

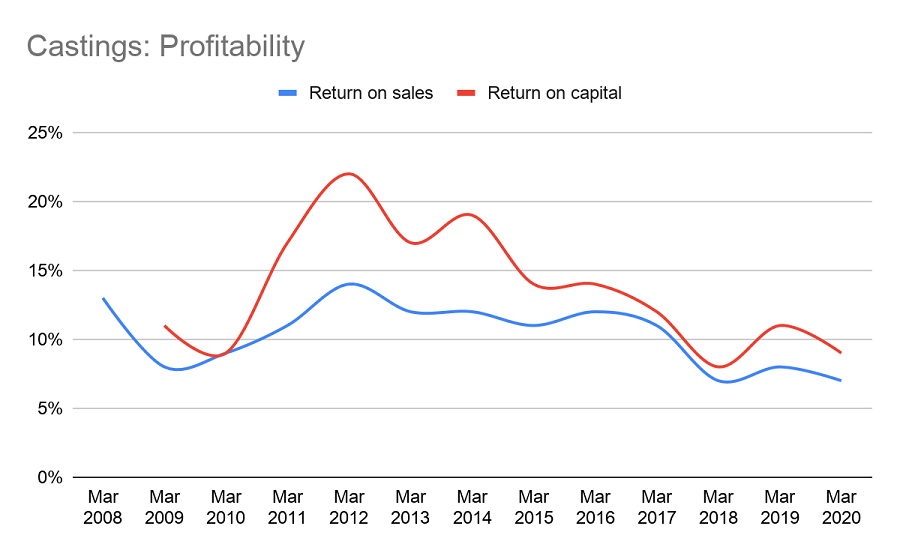

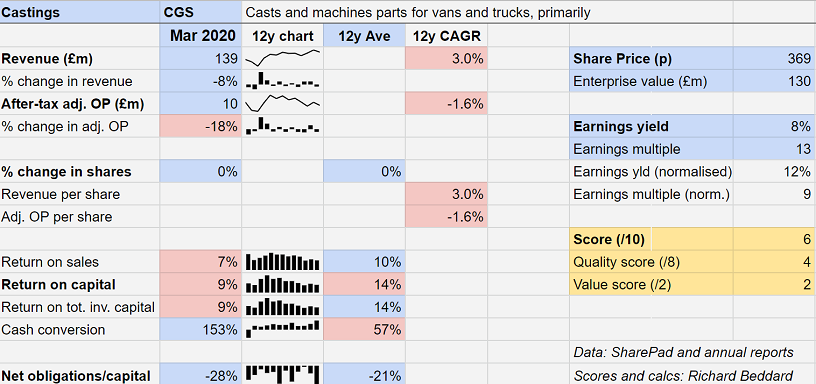

In March 2020, as a global pandemic loomed, the company was still cash rich, but Castings’ after-tax return on sales for the year just gone was 7%, and its return on capital was 9%. These are the figures of a viable company, rather than an outstanding one and the direction of travel does not look good.

Although profitability rebounded after the financial crisis, it has been under pressure for most of the last decade:

Because of its strong balance sheet, Castings (LSE:CGS) will almost certainly survive the pandemic and its economic fallout. The question is, what will emerge when the economy recovers? The highly profitable business of 2011 to 2014, or the merely adequately profitable business it has since become?

Trouble in the machine shop

Castings casts iron and machines it into components, principally for manufacturers of commercial vehicles (trucks and tractors), but it also makes components for cars as well as gates and the hammers used by panel beaters.

The company’s foundries, where the casting is done, experienced a decline in demand in the year to March 2020, even before the pandemic closed customers’ factories in the final two weeks of March. Its machine shop, CNC Speedwell, has been losing money since 2018. In 2020, it looked as though that might change, but the lower volume of castings from the foundries meant less machining, and CNC Speedwell made a small loss.

Castings has never been explicit about the cause of the losses at CNC Speedwell, but it probably took on work for customers outside its commercial vehicle niche, for which it was not equipped or did not have adequate capacity. In recent years, it has retrenched, focusing on machining the output of its foundries for commercial vehicle customers who are outsourcing more manufacturing.

Strength also a weakness

Castings’ strength is also potentially a weakness. It has long associations with three very large customers, Scania, Volvo, and DAF. Together they contributed about 50% of Castings’ revenue in 2020.

The relationship is stable because Castings gives customers what they want, which is rapid prototyping, a high-quality finished product, and the wherewithal, through its own cash reserves, to invest while demand is low but expected to rise.

Once a component is designed for a commercial vehicle, it is likely to remain in use for the lifetime of the chassis (usually about 10 years), which means Castings can expect repeat business. Sales, though, fluctuate roughly in line with demand for the vehicles themselves, which has been stable enough for Castings to profit through thick and thin.

It is a symbiotic relationship but perhaps it cannot be taken for granted. Losing significant chunks of business is not a risk Castings lives with every day, but it does happen. CNC Speedwell lost out in 2017, when Landrover ceased production of the Defender model. Since 70% of Castings’ revenue is earned in Europe, it could lose customers if the terms of trade worsen following Brexit.

One way of making good lost custom is to recruit new customers, and while this happens in the supply chain, Castings also supplies component manufacturers, other European commercial vehicle manufacturers like Daimler also have long standing relationships with foundries in Germany and Turkey.

Castings’ strategy, therefore, is to supply more components to its big customers as they outsource more. So far, though, this strategy has yielded very modest revenue growth and no profit growth at all, mainly due to Castings’ inability to machine more complex components profitably. Castings earned less profit in 2012, than it did in 2008.

Scoring Castings

Does the business make good money? [1/2]

+ Profitable through thick and thin. Achieved 8% return on capital in 2008

? Cashflow improving

− Profit margins are at a record low (7%)

What could stop it growing profitably? [1/2]

+ Resilient balance sheet

? Customers requiring more finished components

? Dependent on three big customers, all European

How does its strategy address the risks? [1/2]

+ Investment in automation and training keeps it competitive

? Yet to demonstrate it can machine components profitably

− Strategy does not address concentration of customers

Will we all benefit? [1/2]

+ Veteran chairman Brian Cooke owns a 4.5% stake

+ Long-lived relationships with customers

+ Employees are a central element of strategy

? Executive pay is generous but straightforward. Bonuses are modest.

− The company could be more open with shareholders

Are the shares cheap [2/2]

+ A share price of 369p values the enterprise at £130 million, about 13 times adjusted profit.

A score of 6/10 suggests Castings may be a good long-term investment but, although prudence is a virtue in times of crisis, I am not confident it will make substantially more profit in, say 10 years’ time. The industry is not graced with bountiful opportunity, and Castings seems to be content with its place in it.

Companies adapting to a new way of life

It’s been a source of reassurance during the pandemic to scroll through messages from companies I follow on Twitter.

When we’re cut off from businesses at home, we can still see them at work. Castings, sadly, is a bit too old-school to tweet, but most of the other companies I follow market themselves on the platform.

I find it a useful way to check up on what companies are saying to their customers, especially at a time when many are saying little to shareholders. Some are clearly adapting their messages and sometimes their products to

our changing way of life.

Churchill China (LSE:CHH) has been explaining how its hardened plates improve hygiene:

Dewhurst (LSE:DWHT) has invented a hands-free lift control panel:

And Renishaw (LSE:RSW) invited us to visit its virtual expo, a great way to learn more about its somewhat magical technologies while its innovation centre is closed:

Richard owns shares in Castings.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

Richard Beddard is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.