Buying a stock is easy: it’s your next move that makes all the difference

Imagine you’ve bought a stock, and it’s suddenly either soared or collapsed. Reda Farran discusses how to think through your next step.

8th December 2023 10:57

by Reda Farran from Finimize

- Investment performance is largely dictated by what an investor does after they buy a stock – specifically by how they deal with both losing and winning positions over time.

- If a stock you’ve bought tanks, revisit your investment thesis. If your thesis still holds, then add to your position. If not, sell it all.

- If a stock you’ve bought soars, don’t be tempted to exit too early. Instead, sell a small amount of your position to realize some gains, and continue to ride out your winners.

Imagine you’ve bought a stock, and it’s suddenly either soared or collapsed. The choice you make next arguably has a bigger impact on your investment performance than the stock you chose in the first place. Here’s how to think through your next step…

Your stock’s collapsed. What should (and shouldn’t) you do?

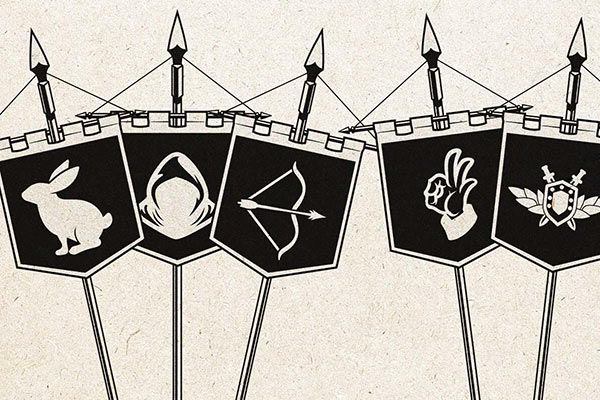

Lee Freeman-Shor – author of an incredible book called The Art of Execution – analysed thousands of trades by some of the world’s best investment managers. And he categorised investors dealing with losses into three different “tribes”: rabbits, assassins, and hunters.

Rabbits do nothing when they’re losing money. They’re more interested in being right than in making money, and when a stock goes against them, they either blame it on bad luck or assume that they’re in the right and the market’s in the wrong. But doing nothing can never be the right decision, because either the stock rebounds – in which case, you should’ve bought more – or it continues to fall, in which case you should’ve sold. And if the stock does nothing, you’d still be better off selling and putting that money to work elsewhere. In other words, don’t be a rabbit.

Assassins are quick to swallow their pride and cut their losses after a stock’s gone against them. As Freeman-Shor explains, they typically sell a stock after a fall of 20% to 30% – before it can go on to lose even more money. Assassins also generally sell positions that are down by less than that range if they’ve not begun to rebound within six months after starting to lose money. After all, there’s little point in hanging onto a losing position if you could invest that money in potential winners.

Hunters, then, add to their position when a stock they’ve bought goes against them. That way, they bring down the average price they pay for a stock. It’s what’s called averaging down on a stock. Here’s the rationale: let’s say you buy a stock for reasons X, Y, and Z. (That’s your investment thesis.) Now let’s say a few months later, the stock’s price is lower, but the reasons – and your thesis – still hold true. If that’s the case, it’s the same opportunity, but you now have the chance to buy in at a lower price.

There are two things to watch out for if you’re a hunter. First, you’ll want to limit your total cumulative loss to a set number – 3% to 5% of your total portfolio, say – rather than repeatedly averaging down on a stock. Second, you won’t want to average down on particularly risky stocks, like those with very high debt burdens or those at risk of technological obsolescence.

So should you be an assassin or a hunter?

Both. The best plan of attack is this: if a stock you’ve bought is down about 25% because your investment thesis is slipping away, you should be an assassin and cut your losses. But if your investment thesis still holds, you should add to your position like a hunter.

That’s why you might want to reconsider ever investing your full intended amount into a new stock, instead investing around 80% into it. That way, if the stock goes up by 25%, it’ll take the position to your intended size. But if the stock goes down 25% and your investment thesis still holds, you’ll have the opportunity to increase your position to the intended amount – but at a lower price.

Your stock is soaring. What should (and shouldn’t) you do?

Now, when it comes to gains, Freeman-Shor categorised two tribes: raiders and connoisseurs.

Raiders are quick to sell their winners and pocket their gains. But that could mean missing out on a lot more potential upside – and that’s what often happens, according to Freeman-Shor.

That makes sense when you think about it: the best investors don’t take that strategy. You don’t see Warren Buffett rushing to sell his entire holding in Apple after making a nice gain. He takes the connoisseur strategy and adds to his billions.

Connoisseurs ride their winners, potentially realising some of their gains by selling small amounts along the way. Freeman-Shor describes connoisseurs as sometimes pocketing a little profit by selling 10% to 20% of their total position every time it rises by 30% to 40%. Cashing in intermittently allows you to see the benefits of your smart investments without sacrificing your long-term wealth aspirations.

As for when you should finally exit your position, well, that can be a tougher call. But there are two signs it might be a good time to bow out: when your investment thesis breaks down, or when your stock falls from its peak by a predetermined percentage. And, generally, 30% to 35% is a good guideline.

So there you have it: aim high by bringing out your inner hunter, make a killing by bringing out your inner assassin, and live a life of luxury as a connoisseur. But whatever you do, don’t be a rabbit or a raider…

Reda Farran is an analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of abrdn.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.