Are these investment trusts in poor or rude health?

Kepler Trust Intelligence assesses the vital signs of listed private equity and shares its verdict.

10th May 2024 14:00

This content is provided by Kepler Trust Intelligence, an investment trust focused website for private and professional investors. Kepler Trust Intelligence is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. It is provided for information only and does not constitute a personal recommendation.

Material produced by Kepler Trust Intelligence should be considered a marketing communication, and is not independent research.

Buyout giant CVC Capital Partners (EURONEXT:CVC)’ IPO a couple of weeks ago has been a blockbuster success. Why, at the same time, does the FT appear to ‘have it in’ for the private equity industry?

Coverage of private equity-related news flow is generally sceptical of the industry’s value add, scornful of those who invest in private equity, and predict its (imminent?) demise.

- Invest with ii: SIPP Account | Stocks & Shares ISA | See all Investment Accounts

At the same time, discounts across the listed private equity (LPE) sector continue to remain at extremely wide levels – both in absolute terms, but also relative to history and the wider investment trust sector. The market too, seems to be taking a dim view.

A warning sign?

Covering the news that CALPERS, the US’s largest public pension plan is to increase its exposure to private markets from 13% to 17%, the FT’s unhedged column of 20 March 2024 neatly summarised its disbelief that this might be a good move in three points:

- The size of the private equity industry now means significantly more competition for assets, higher purchase prices, and therefore lower returns in the future

- Higher interest rates mean more expensive debt, and combined with less availability of debt, mean more equity in capital structures and therefore lower future returns

- “Private equity portfolios are akin to leveraged public equity portfolios”. They argue that given public equity portfolios have overshot their long-term returns in recent years, the expectation is that returns will mean revert, and be lower in the future. Therefore, the FT argues, private equity portfolio returns will, in lock-step, also be lower.

At a very high level – so high that one can’t distinguish between one portfolio or another – perhaps these arguments have some resonance (other than the last one, which we can’t understand at all). That said, the FT presupposes that even as the PE industry has grown, it is still just chasing the same deals.

On the other hand, perhaps the PE industry is actually chasing more deals, which would lead one to query why this in itself would lead to fiercer competition? If the FT is correct, and PE competition is a whole lot more fierce, then would this not also benefit exit multiples, given one PE firm often sells to another? Surely this would benefit the mature portfolios of PE investments we find in the LPE sector?

In our view, the truth is that the universe of potential investments is significantly broader for private equity managers than it is for investors who restrict themselves only to quoted equities. Given private equity is ‘go-anywhere’, other than private equity portfolios, potential investments can be found in quoted companies, non-private equity-backed/family-backed businesses and state-owned businesses.

After all, private companies in general make up a very significant part of modern economies. For example, in the UK according to government statistics, there were around 8,000 large businesses in January 2022 (with 250 or more employees). While representing just 0.1% of the business population, these business support 39% of jobs and nearly half of all business turnover.

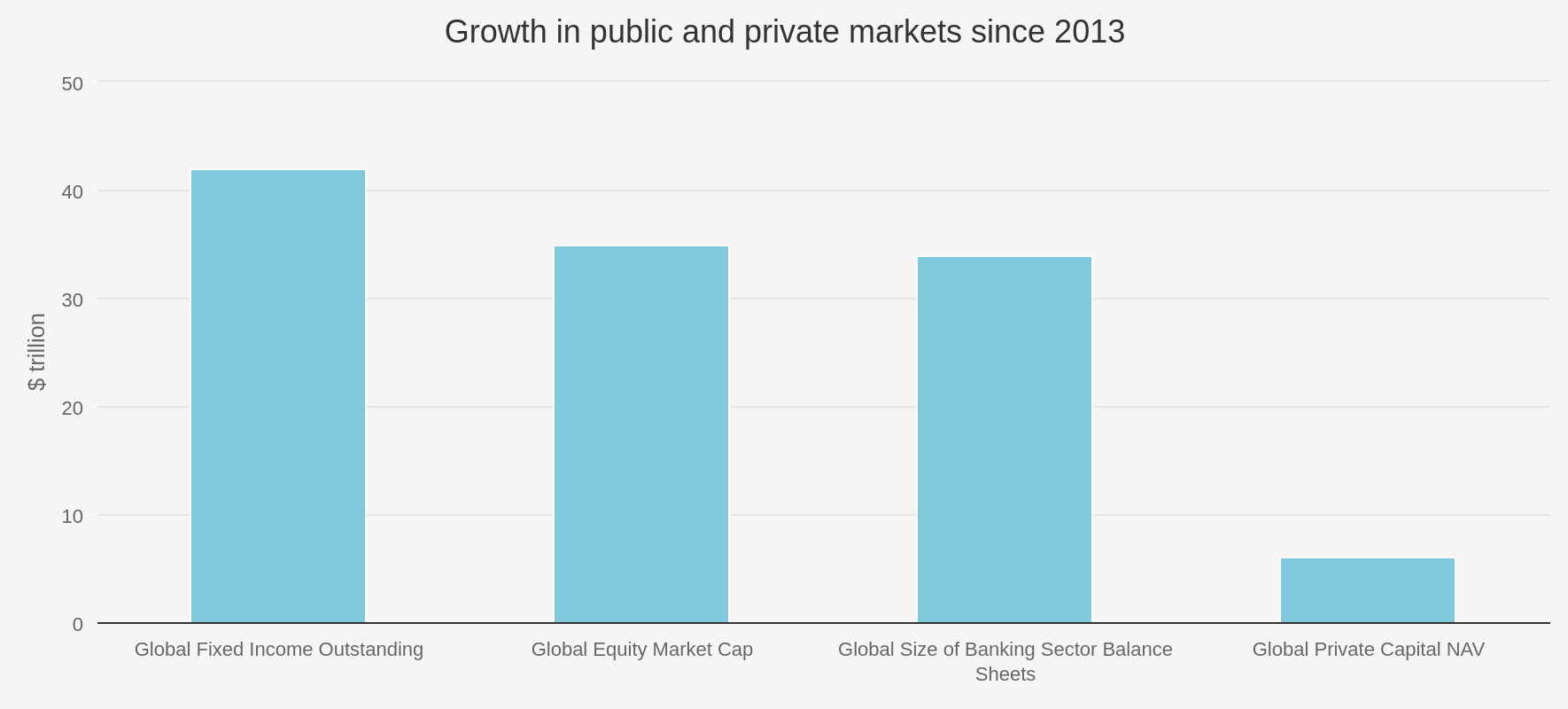

As such, just because PE has grown relative to its own size, it doesn’t mean that there is less runway ahead of it. One graph from Hamilton Lane’s 2024 overview of private markets report stood out for us in this regard, which we reproduce below. It highlights that private markets (comprising buyouts, VC, infrastructure and real estate funds) have actually grown in absolute terms by significantly less than government bond markets, quoted equities’ market capitalisation and bank balance sheets.

In our view, the FT’s argument is a bit like saying that because the US is circa 70% of the MSCI World Index, you shouldn’t invest in it anymore because it must be ex-growth.

ASSET CLASSES

Source: Hamilton Lane. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

Certainly, more competition for assets and less low-cost debt washing around will probably result in marginally lower returns over the long term. However, we disagree that these are material contributors to the medium-term prospects for private equity in general, and for the listed private equity sector specifically, consisting as it does of fully invested portfolios.

While the FT’s unhedged article doesn’t in our view land any hammer blows, there are other potential signs that the private equity industry may not be in the rudest of health.

Before we get the scalpel out and take a look inside the anaesthetised body of the LPE sector to properly examine the vital organs – revenue and earnings growth – let’s take a look at the outward signs of sickness: the macro considerations that those looking at the LPE sector might want to consider.

Deals, deals, deals

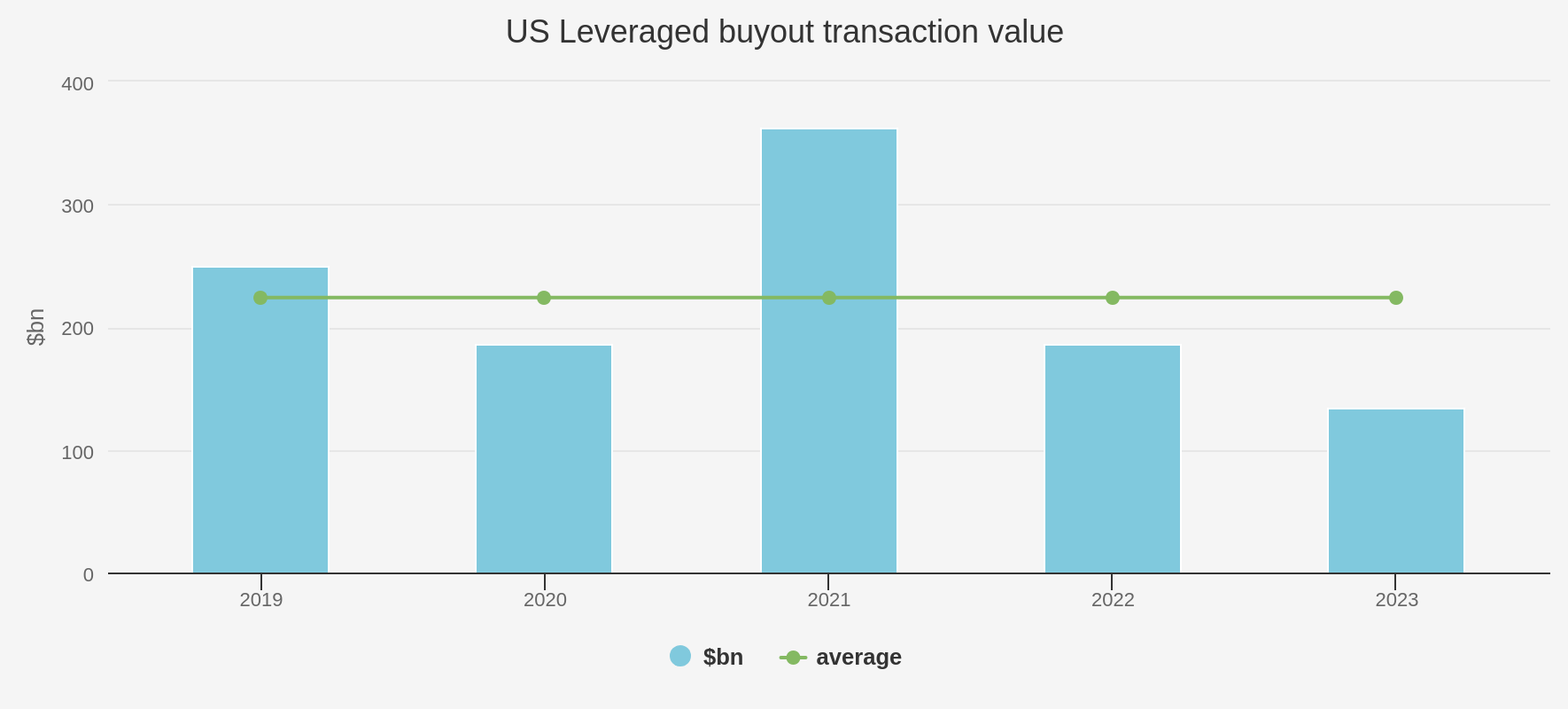

Almost all LPE trusts have reported that deal activity within their underlying portfolios has slowed. We show below data reproduced from Apax Global Alpha’s annual results, which shows US buyout deal volumes have declined quite markedly in 2023 from 2022’s levels. According to Bain, deal activity is at its lowest level since 2016. In our view, this is largely a result of a hangover from the rapid rise in interest rates seen in 2022. Higher interest rates bring uncertainty, and they also mean that deals need more equity in their capital structure. Despite record firepower ($789 billion at the end of 2023, according to Preqin) private equity deals aren’t getting done at prior volumes. In our view, this is perfectly logical. Because private equity funds don’t need to sell, managers (General Partners or GPs) might be forgiven for wanting to wait until interest rates fall, thereby helping improve valuations.

It is also true that after a decade of ultra-low interest rates, for GPs that are looking to invest it may make sense to delay making purchases until it is clear what the economic background may look like. In 2022 inflation took off, and resulting rate rises initially gave rise to worries of an economic hard landing. Now that those worries look less founded, we may see deal activity start to tick up. Without evidence of a return to the feverish pace of activity of the past, GPs can bide their time. It is worth remembering that GPs are remunerated not on deals done, but on realised IRRs for their funds. If competition for assets they are buying is not high, GPs can afford to be very selective. And for sellers, if higher interest rates are seen as a temporary phenomenon, then it makes sense to hold on and maximise returns – especially when companies are profitable, and are continuing to grow earnings at a good clip, paying down debt on the way.

US BUYOUT DEAL VOLUMES

Source: Apax, sourced from LCD. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Valuations

Some critics of private equity say that the reason for deal volumes falling reflects an unwillingness of GPs to face the reality that the book-values of their investments are too high, and need to be written down. The chair of Pantheon International Ord (LSE:PIN)highlighted in the most recent interim report for the trust that valuations were one of the main “distrust factors” that the LPE sector faces from investors. He reflects on criticism that the sector is burying its head in the sand, and that valuations haven’t been written down to reflect the higher interest rate environment. “While many public market investors were expecting a large drop in private equity valuations during 2023, translating into a sharp dip in Listed Private Equity NAV performance, this has not happened”. His argument, which in our view is reflected in historically published statistics, is that valuations were never written up that much, so they don’t need to be written down either.

That said, on the surface relative to quoted markets valuations those within the LPE universe are optically higher on one measure (EV to EBITDA). Our analysis of the most recently published portfolio valuation statistics indicates the average EV/EBITDA valuation of all of the LPE trusts is 16x (as at 30/12/2023), which compares to Bloomberg’s equivalent 11.9x for the MSCI World Index. CT Private Equity Trust Ord (LSE:CTPE) has the portfolio with the lowest valuation, which may reflect the trust’s focus on the lower mid-market, investing in companies which are typically smaller than those of the rest of the peer group. Other than size, there will be lots of other adjustments that one might make when comparing valuations, especially when compared to an index such as the MSCI World. For example, the sector make-up of PE portfolios and that of the MSCI World is very different. The MSCI World’s valuation will be dragged down by the traditional ‘value’ sectors like mining, energy, banks and utilities, whereas PE portfolios typically have no exposure to any of these, and tend to be more exposed to technology and industrials. As such, meaningful comparisons are hard to make on this basis. And as the table further below shows, LPE portfolio companies are growing in aggregate at significantly higher rates than that of the MSCI, which clearly justify a higher valuation.

Relative valuations are one thing, but how do valuations stack up in absolute terms? Again, it’s hard to make broad judgements. An average EV to EBITDA of 16x may be considered high. In reality, valuations can only really be seen in the context of each company’s characteristics such as long-term growth prospects, of margins, and the balance sheet make-up of each company. As we show in the table below, LPE portfolios are significantly more highly geared than the average for the MSCI World Index. However, across the trusts there is a wide degree of variance – with HgCapital Trust Ord (LSE:HGT) (high-margin and high-growth software and tech-enabled service businesses) significantly higher than peers at 7.4x in absolute terms, but there are others which are higher on a debt-to-equity basis. Certainly the overall statistics suggest gearing is reducing in absolute terms year-on-year, unsurprising given the spike in interest costs and the fact that portfolios are maturing.

LPE SECTOR: UNDERLYING LEVERAGE & VALUATIONS

| TICKER | SAMPLE | SAMPLE % OF PORTFOLIO | NET DEBT TO EBITDA (X) | VALN:EV TO EBITDA (X) | NET GEARING % (DEBT TO EQUITY) |

| Apax Global Alpha Ord (LSE:APAX) | Private equity portfolio | 80 | 4.6 | 16.6 | 38 |

| Patria Private Equity Trust (LSE:PPET) | Top 50 | 40 | 4.3 | 14 | 44 |

| CT Private Equity Trust Ord (LSE:CTPE) | Co-investments | 45 | 3.1 | 11 | 39 |

| HgCapital Trust Ord (LSE:HGT) | Top 20 | 76 | 7.4 | 26.1 | 40 |

| HarbourVest Global Priv Equity Ord (LSE:HVPE) | Sample | 30 | 4.6 | 14.8 | 45 |

| ICG Enterprise Trust Ord (LSE:ICGT) | Enlarged perimeter | 66.4 | 4.7 | 14.4 | 48 |

| NB Private Equity Partners Class A Ord (LSE:NBPE) | Top 30 | 75 | 5.3 | 14.9 | 55 |

| Oakley Capital Investments Ord (LSE:OCI) | Whole portfolio | 100 | 4.2 | 16.4 | 34 |

| Princess Private Equity Ord (LSE:PEY) | Sample | Not disclosed | 5 | 17 | 42 |

| Pantheon International Ord (LSE:PIN) | Sample | c. 60 | 5.4 | 18.5 | 4 |

| Average | 4.9 | 16.4 | 42 | ||

| MSCI World Index | 1.5 | 11.9 | 14 |

Source: Kepler Partners, Bloomberg. Statistics as at each trust’s last published date. PPET: Patria Private Equity Opportunities (abrdn Private Equity Opportunities until 1/5/2024). Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

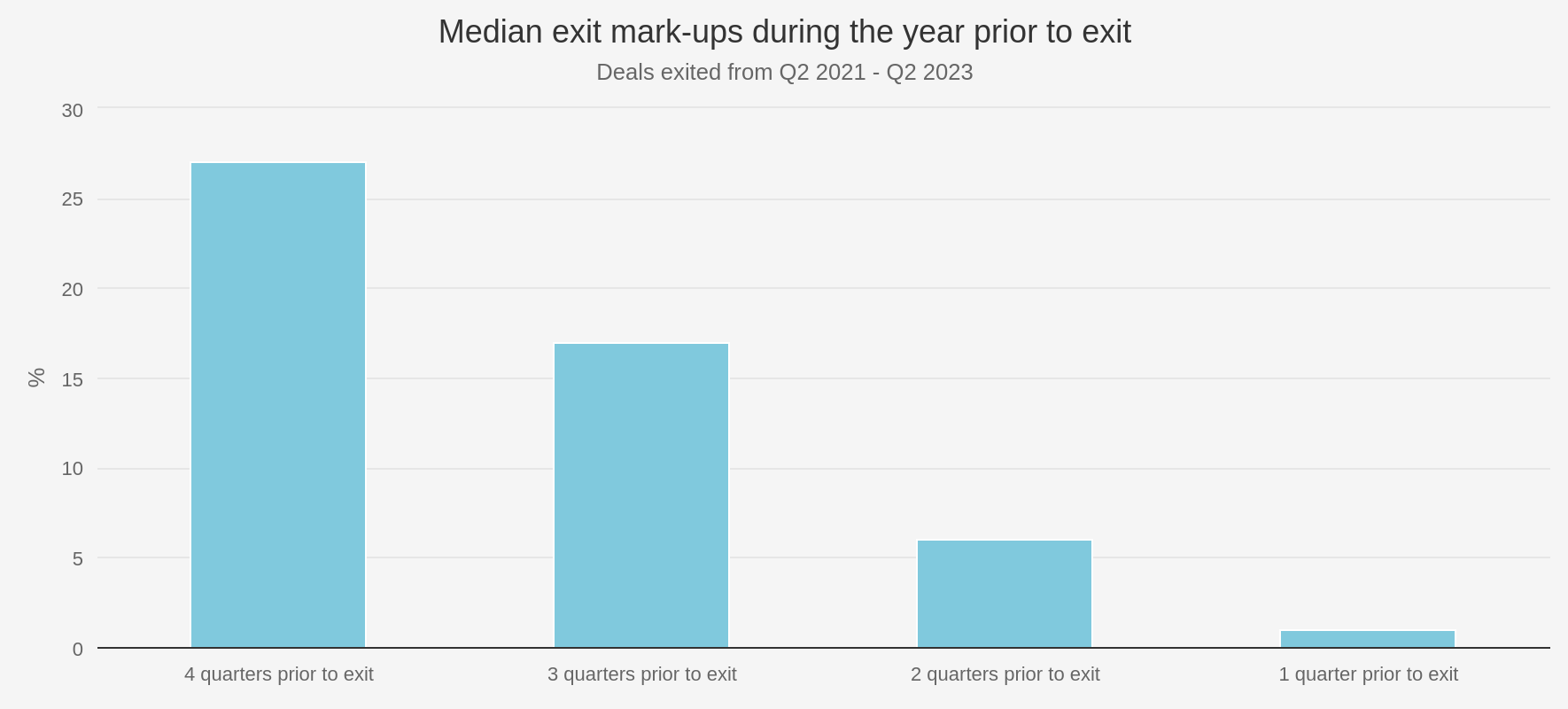

Given the specifics involved in company valuations, the only true way to determine whether valuations are fair is to compare them with what companies are eventually sold at. Following the LPE sector for a number of years, we have observed it is very rare for companies to announce sales of investments at below carrying value. In our view, this is no accident: valuation policies tend to be conservative, necessarily including an illiquidity discount. But private equity conventions also dictate that GPs tend to want to deliver good news to their investors on a sale, which includes a ‘pop’ to the valuation. A cursory look back at RNS announcements over the last year or two confirms that this pattern still holds, with sales from LPE portfolios continuing to be achieved at mid-teen uplifts to valuations at the least. This reinforces our view that valuations remain conservative, although we do accept that with deal activity sluggish, the sample size on which uplifts are being achieved is smaller, and so therefore one’s confidence in ALL valuations being conservative must be less. Hamilton Lane have a much wider perspective, monitoring the entire global buyout sector. Their analysis, shown below, of the period since the start of 2021 backs up what we see anecdotally in the LPE sector’s RNS announcements.

BUYOUT UPLIFTS

Source: Hamilton Lane. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Portfolios are maturing

We have made several references to deal activity slowing so far, showing it is an important vital sign of a healthy private equity industry. According to Bain’s 2024 Global Private Equity report, there are 28,000 unsold companies in buyout portfolios currently representing $3.2 trillion of value. Forty-six per cent of these are more than four years old, which assuming the number of companies is evenly distributed, means around 13,000 companies and $1.5 trillion are currently theoretically on the block for a sale.

Clearly, the knock-on effects of fewer deals happening is that LPE portfolios are becoming ever more mature, and that LPE’s commitment cover is falling (of which more below). All things equal, more mature portfolios can in our view be seen as a positive, given underlying companies will (theoretically at least) be further along their private equity-backed transformation, but perhaps more importantly, will also be de-risked having paid down debt with surplus cashflow.

That these companies are closer to being sold can be a curse or a blessing depending on your view. A reasonable proportion of the value gain of any buyout investment is only recognised when it is sold. However, it’s hard to imagine that the highest prices for private equity-backed businesses can be achieved when GPs worldwide are simultaneously trying to offload swathes of mature businesses at the same time. That said, the aforementioned record level of dry powder in the private equity market may mean that further rounds of private equity ‘pass the parcel’ cannot be ruled out. CTPE specifically targets companies and GPs in the lower mid-market. The smaller size of their exits typically makes these companies ideal targets for mid-market buyout funds. CTPE reported that during 2023, 63% of their exits were to other private equity managers.

With less cash coming back to trusts from sales, commitment cover across the LPE sector is falling. Trusts making primary investments in PE funds commit capital over the long term, and have no control over when it is ‘called’ or invested. With investments outpacing realisations, cash balances are reducing and most trusts have significant overdraft facilities on hand to provide firepower if required. This was the LPE sector’s undoing in the global financial crisis of 2008. It is therefore reassuring that commitment cover for the sector is nowhere near as high as in 2006-07, which then resulted in several (now defunct) trusts in the sector having to launch heavily discounted ‘rescue’ rights issues in 2008-09. With illiquid assets, boards must always tread carefully, and investors’ enthusiasm for discounts to NAV must always be balanced with a keen awareness of each trust’s outstanding commitments and balance sheet position.

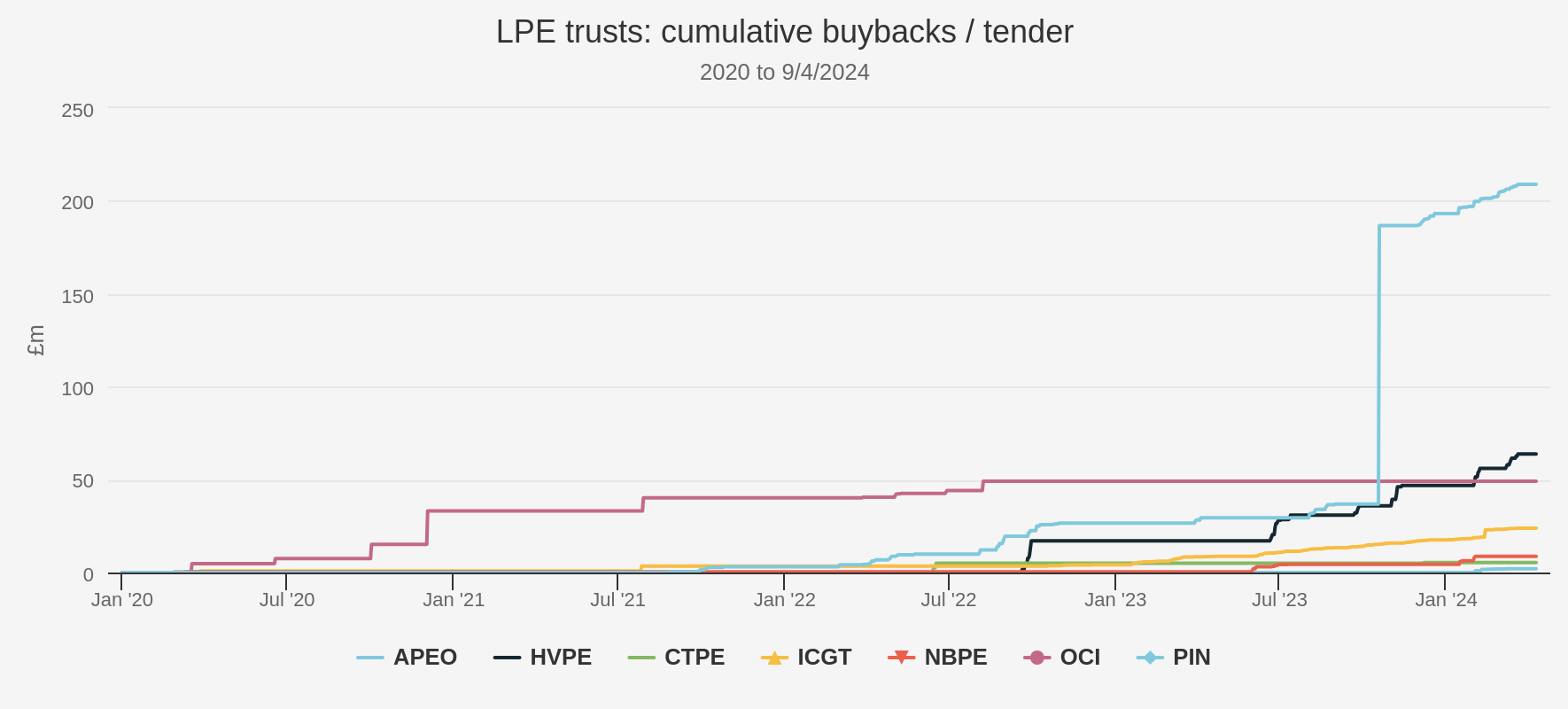

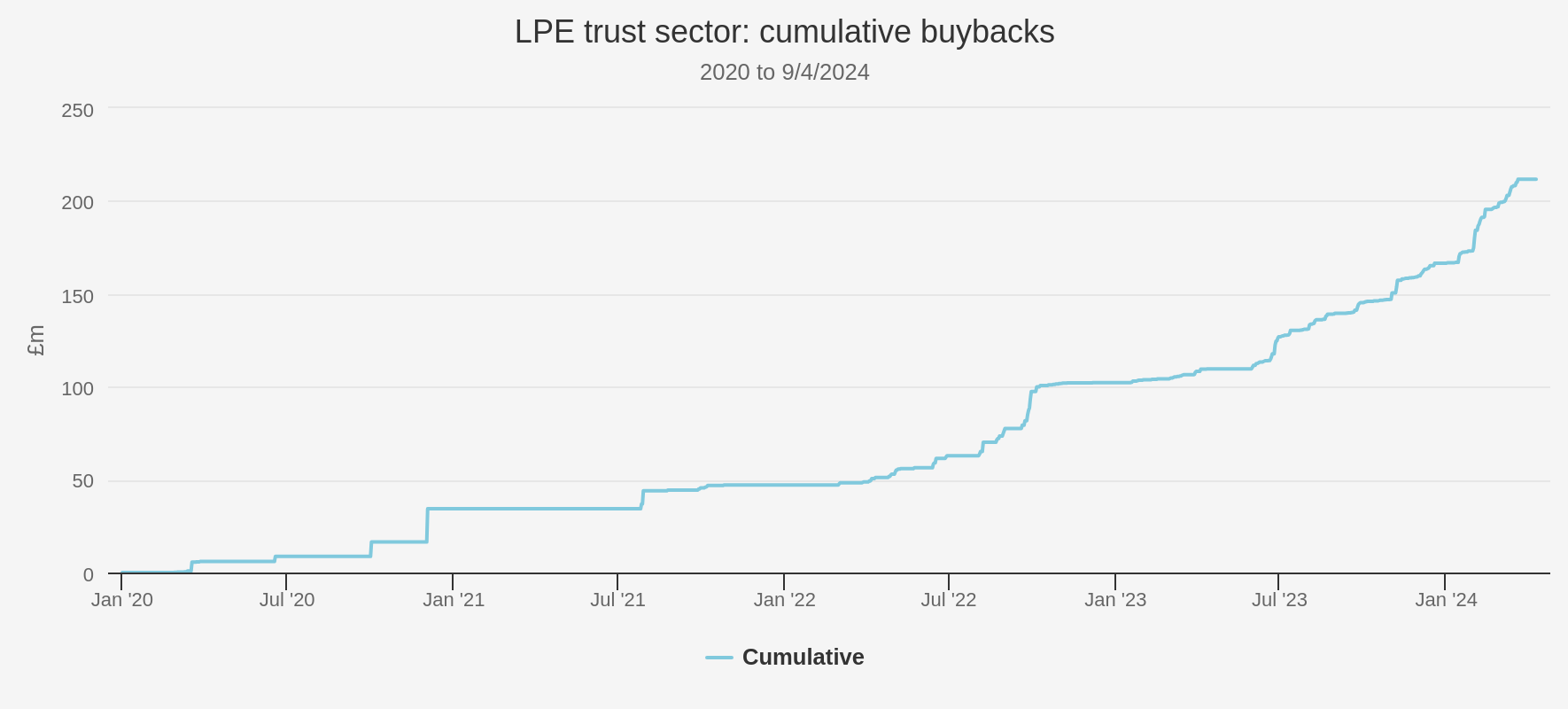

In this context, we highlight the below graph which shows that some boards are increasingly buying shares back, which in our view can be taken as a vote of confidence in the respective trust’s financing position and possibly the conservative nature of valuations. Rather than ramping up commitments with surplus capital, some boards are choosing to return capital by buying shares back at significant discounts, providing a lower-risk way of boosting the NAV.

We describe buybacks as ‘lower risk’ rather than ‘risk free’, because in a black-swan scenario, deploying capital in this way may leave a trust more overextended than it might otherwise be, given it uses up cash but also depletes the asset base of the company and at the same time increasing the gearing ratio of any borrowings employed. That said, the sector’s increasing focus on buybacks is to be welcomed, in our view. This wave of ‘woke’ thinking from LPE boards, who on the whole have previously resisted buybacks, has perhaps been prompted by their becoming increasingly independent of managers, but is undoubtedly also a reflection of the wide discounts to NAV that LPE trusts in particular continue to trade at. PIN has been one of the trusts leading the charge in terms of aggressively employing buybacks (and a tender offer) to return capital to shareholders, and boost returns for existing shareholders.

LPE SECTOR: BUYBACKS/TENDER SINCE 2020

Source: Morningstar, Kepler Partners.

Secondaries

Buybacks are just one sign that boards see LPE discount levels as too wide. At the same time, the pricing of secondaries (representing the secondhand market for intuitional private equity portfolios) has seen a recovery, with buyout portfolios trading at around 91–96 cents in the dollar in Q1 2024, up from 85–90 cents in Q1 2023 according to PJT Partners. This is in the context of significantly higher volumes of secondary transactions over the year, which are running at c. 20% higher than the same quarter last year, according to their Q1 2024 Secondary Market Insight report. By comparison, listed private equity trusts have generally always traded at a further discount to the prices that secondaries attract. However, PJT Partners statistics would suggest that amongst institutional investors, demand for private equity portfolios is roaring back.

Secondary-interest discounts widened out in 2022, we would argue a reflection of technical factors rather than sentiment. Many institutional investors in private equity found themselves bumping up against the top of their asset allocation models as regards allocations to private equity. With deal activity in the doldrums, and long-term commitments still outstanding, by selling PE interests as secondaries, such investors were able to generate cash to meet potential future calls on capital, but at the same time keeping their overall asset allocation in balance. In our view, that volumes remain high is not the smoking gun that LPE’s detractors are looking for, especially given that secondary discounts have narrowed once again.

Earnings growth: the long-term driver of PE returns

Despite what the FT’s journalists appear to believe, earnings growth is the main determinant of long-term private equity returns rather than asset stripping and leverage. Leverage and multiple arbitrage are clearly contributors to returns in some cases and at some points in the cycle. However, we believe that there is good evidence to suggest from managers such as HGT and PIN that over the long term it is private equity managers’ ability to select and invest in companies capable of strong revenue and earnings growth, as well as their ability to influence this growth, that is the long-term and more persistent driver of value. Indeed, given the cyclical vagaries of markets and pricing, one might argue that delivering revenue and earnings growth is the main variable that GPs are able to influence directly, year in, year out.

Hamilton Lane echo this, and they state in their 2024 report that private equity outperformance of public markets is "not about magical financial engineering or wizardry around leverage. It’s about boring operational performance”. They argue that private equity managers aren’t necessarily smarter than their public counterparts, but they believe PE-backed companies’ governance is better, and the type of companies they choose to invest in is different, both of which contribute to better performance. Their analysis shows that buyout funds have generally avoided some areas that are more represented in the public markets and that have been highly volatile and not very good performers, notably materials and consumer. Instead, buyout has generally been overweight in sectors that have shown greater growth and resilience during economic cycles, especially information technology and industrials. More importantly, the size of companies varies drastically, with Hamilton Lane providing statistics that an average company size in the S&P 500 Index is $32.5 billion versus $328m in their buyout universe. Hamilton Lane believe that the degree of control that can be exerted over a smaller company is enormous compared to a larger one, thereby giving a “greater ability to create paths for operational growth”.

Bain’s annual private equity report is also keenly awaited. The Bain report looks at the value-creation drivers for global buyouts in the ten years to 2023. They believe that the majority of value creation is down to revenue growth, but attribute 47% of value gains to multiple-expansion. In our view, this may have more to do with the period in which their study was conducted, rather than being representative of the long-term picture. Deals exited during the last ten years will likely have been made during a period of falling interest rates, which may have delivered a helpful (but not necessarily anticipated) tailwind to returns. The managers of NB Private Equity Partners Class A Ord (LSE:NBPE) have observed that on the deals they have been reviewing over the last year or so, GPs are pricing their investments to achieve strong IRRs but are not ascribing any expectation for a change in multiple. Indeed, in some cases, we understand GPs are investing on an expectation that the multiple will contract.

If earnings growth is the main, long-term determinant of returns, then long-term investors should therefore focus mainly on this measure when taking the pulse of the LPE sector. As we show below, the patient appears to be in rude health, with strong earnings growth in absolute terms even during the ‘tough’ years of 2022 and 2023. In fact, LPE portfolios have significantly outperformed the MSCI World Index too. As we refer to above, this gives us confidence that higher aggregate valuations than the average for the MSCI World are justified. Growth has moderated during 2023, and we would highlight that these earnings statistics are BEFORE interest (and tax, depreciation and amortisation). With interest costs remaining elevated, it is worth highlighting that we would imagine that underlying earnings growth post interest costs would have declined further than these statistics suggest. These headwinds – which affect earnings AFTER interest costs – could be one reason why deal activity has slowed, but it is also possible to see that if interest rates fall, these headwinds will turn into a tailwind when comparing year-on-year growth. Falling interest rates are therefore a meaningful potential catalyst for improved sentiment towards LPE trusts.

LPE SECTOR: UNDERLYING REVENUE & EARNINGS GROWTH

| 2023 | 2022 | |||||

| Ticker | Sample size | Sample % of PE p/f | Revenue growth | EBITDA growth | Revenue growth | EBITDA growth |

| APAX | Private equity portfolio | 80 | 12.1 | 18 | 21.5 | 18.5 |

| PPET | Top 50 | 40 | 16 | 23 | 23 | 24 |

| CTPE | Co-Investments | 45 | 17 | 29 | 36 | 22 |

| HGT | Top 20 | 76 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 25 |

| HVPE | Sample | 30 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 21.6 | 20.2 |

| ICGT | Enlarged perimeter | 66.4 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 22.2 | 21.8 |

| ICGT | Top 30 | 36.8 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 21.9 | 21.6 |

| NBPE | Top 30 | 75 | 11 | 15 | 27 | 20 |

| OCI | Whole portfolio | 100 | 14 | 22 | ||

| PEY | Sample | Not disclosed | 13 | 13 | 24 | 16 |

| PIN | Sample | c. 60 | 18 | 18 | 23 | 10.6 |

| Average | 15 | 18 | 25 | 20 | ||

| MSCI World | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Source: Kepler Partners, Bloomberg. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Conclusion

Good news. Despite some initially concerning symptoms, the patient has been found fit and healthy. Certainly, LPE needs to take things easy until a full recovery (in deal activity) has been made – the catalyst for which is likely a meaningful decline in interest rates. While we wait, care must be taken not to take too much medicine in the form of buy-backs, which if taken to excess may result in the patient feeling unsteady and vulnerable to further shocks. Fundamentally, the vital signs of continued strong revenue and earnings growth should enable a full recovery, and narrower discounts over the long term. As your doctor, I’d like to ask the patient to check in regularly – say every six months – and we can keep an eye on things. In the meantime, keep taking the medicine (see below), but – remember – do try to avoid over-medicating.

LPE SECTOR: CUMULATIVE BUYBACKS (EXCL TENDER) SINCE 2020

Source: Morningstar, Kepler Partners

Kepler Partners is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. Neither Kepler Partners or interactive investor will be responsible for any losses that may be incurred as a result of a trading idea.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Important Information

Kepler Partners is not authorised to make recommendations to Retail Clients. This report is based on factual information only, and is solely for information purposes only and any views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment.

This report has been issued by Kepler Partners LLP solely for information purposes only and the views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment. If you are unclear about any of the information on this website or its suitability for you, please contact your financial or tax adviser, or an independent financial or tax adviser before making any investment or financial decisions.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. The information in this website is not for distribution to and does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy any securities in the United States of America to or for the benefit of US Persons.

This is a marketing document, should be considered non-independent research and is subject to the rules in COBS 12.3 relating to such research. It has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research.

No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not to be taken as advice to take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm's internal rules. A copy of the firm's conflict of interest policy is available on request.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

PLEASE SEE ALSO OUR TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Kepler Partners LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales at 9/10 Savile Row, London W1S 3PF with registered number OC334771.

Kepler Partners LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.